The Poet's Corner

It’s confession time.

The Vincent Starrett poetry anthologies.

“Here I look like a dying poet. Dying poets have a habit of becoming famous, but somehow I have defied this tradition.” — Vincent Starrett in The Last Bookman.

When I started collecting Vincent Starrett’s writings, there was one category of his work that I largely ignored: his poetry.

Except for “221B,” I tended to glaze over as I looked at a Starrett verse. The problem was no doubt mine. Poetry is not my cup of single malt. (I also don't drink single malt out of a cup. Cups are for coffee, which, as Steven Rothman says, “I drink black. Like my soul.” But I digress.) As time went on, I started to spend a little more time reading Starrett’s poetry. I also found collecting his poetry anthologies to be fun, since most are readily available at reasonable fees.

Along the way I grew to appreciate some—though I must admit, far from all—of Starrett’s verse. So, seeing as how April is National Poetry Month, and this is April, we’re going to spend to spend a little time with Vincent the poet.

(And for those of you who don’t like poetry, try a classic blog post about an equally classic Starrett image. Enjoy.)

Here’s how we’re going to do this: We will look at each of Starrett’s major poetry anthologies and pick out one representative verse to see what there is to learn.

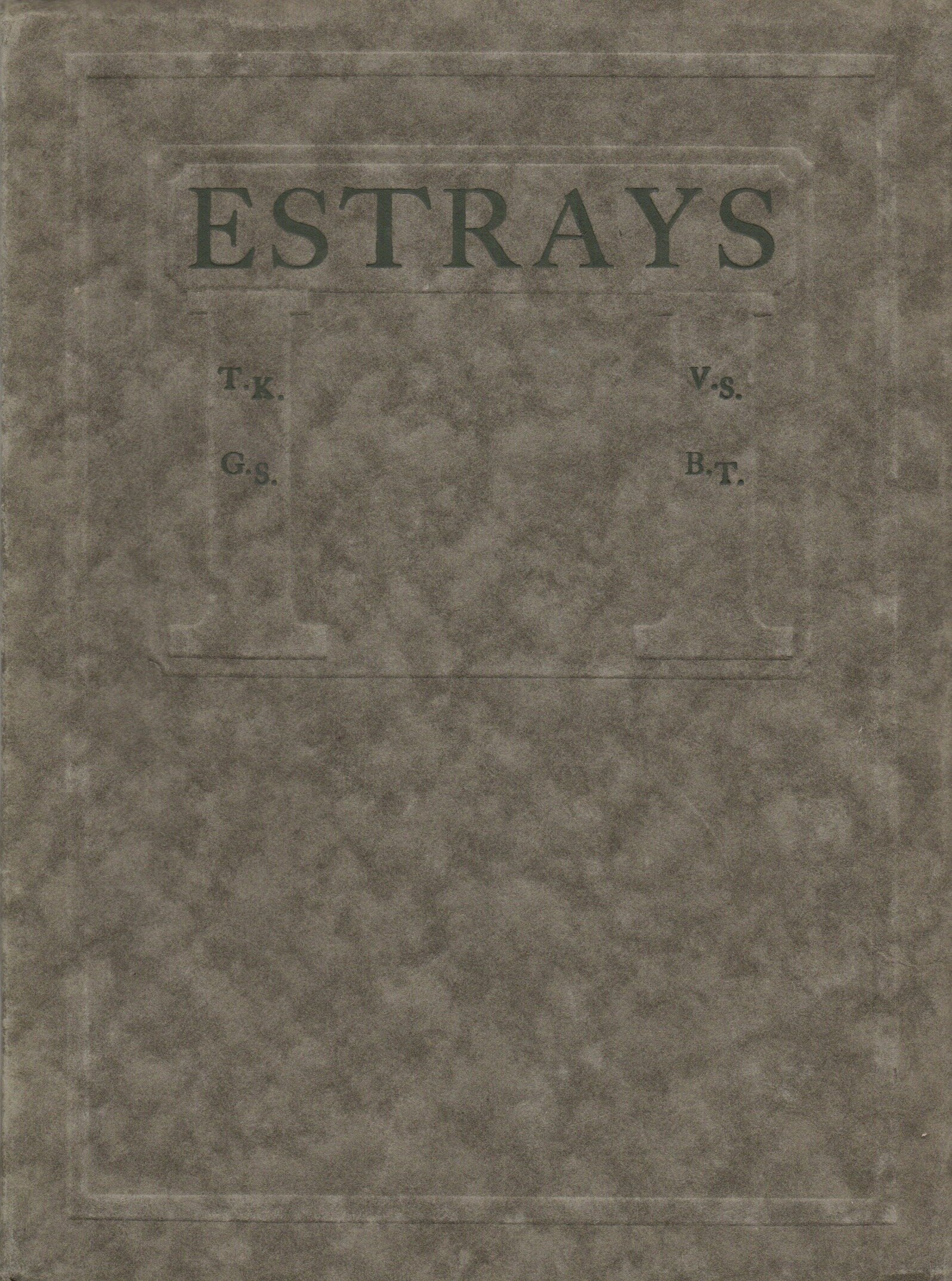

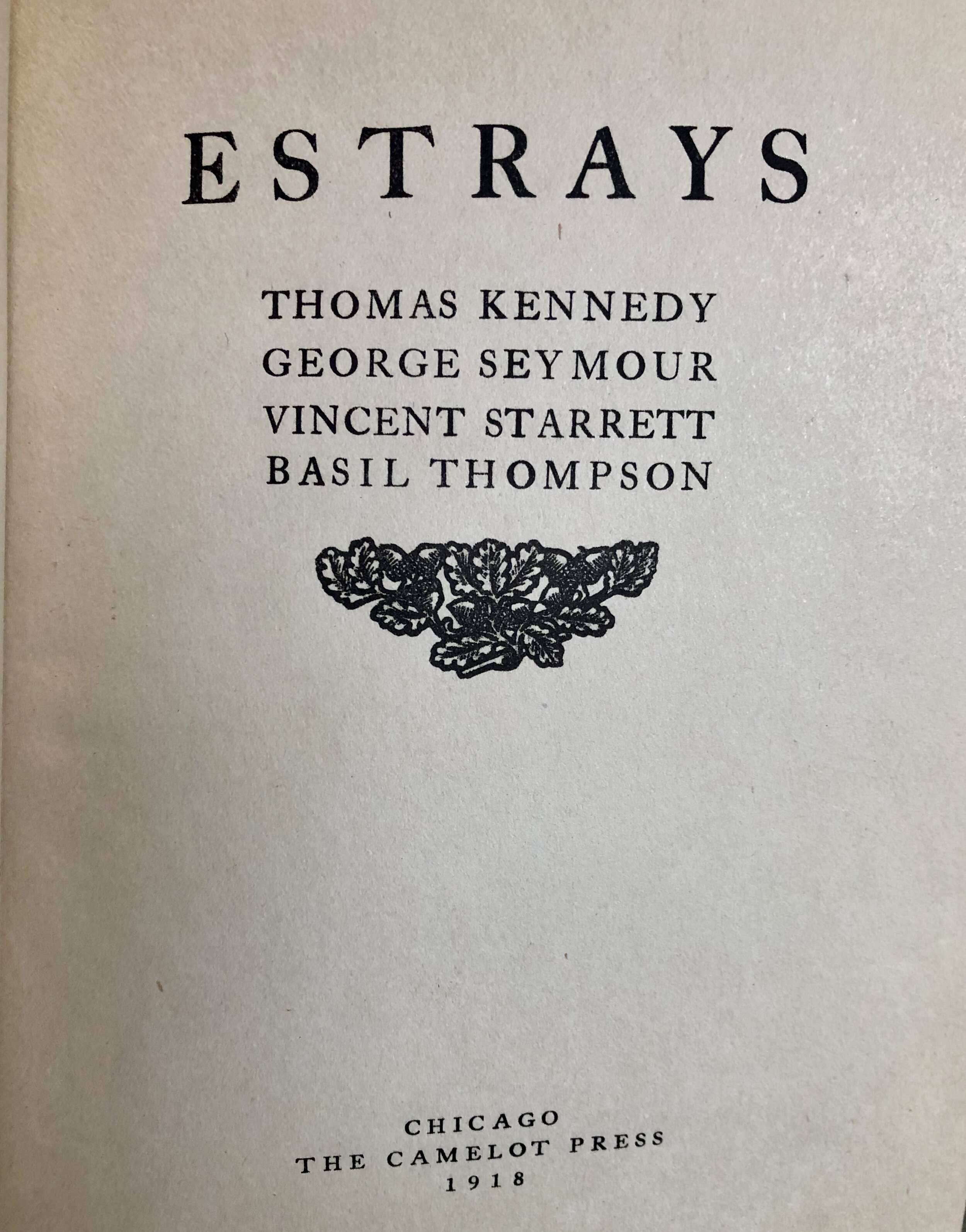

The Book: Estrays

Right away, I am going to break the pattern of our journey, because there are two versions of Estrays. Published first by The Camelot Press in a softbound edition of 250 in December 1918, this volume holds selected poetry by four of Chicago’s up-and-coming versifiers: Starrett, Thomas Kennedy, George Seymour and Basil Thompson. A second edition came in 1920 published by The Bookfellows of Chicago, with much the same content and a few more poems by each of the four.

The Poem: “Shop Windows in Winter”

Like most of his poems gathered here, Starrett’s head is in the romance and adventure novels of his childhood. The title might lead you to believe this will be an ode to the holiday department store windows in Chicago. Instead, Starrett is passionately going on about pirate kings, Egyptian plunder, and Samarcand. No, sorry “Samarcand!” (Now more frequently spelled “Samarkand.”) Decades later, Starrett would repudiate his early verses of this kind. I think of this as his “Head in the clouds” period, where he produced heated lines about love and ancient cities, immortal oceans and unreachable women with enigmatic eyes. It’s easy to agree with his later assessment, but in fairness, the other three poets sound just as lovesick. Starrett was writing as the young men of his era did.

There are two poems in this collection that would remain favorites of his and show up in later anthologies: “Villon Strolls at Midnight” and “Don Quixote.” Both are based in literary legends: Villon the 14th century criminal who turned his career of crime into the legend of a thief with a heart of gold; and that windmill fighter created by Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote of La Mancha. Starrett would always be at this best writing about the most true-to-life people he knew: literary creations.

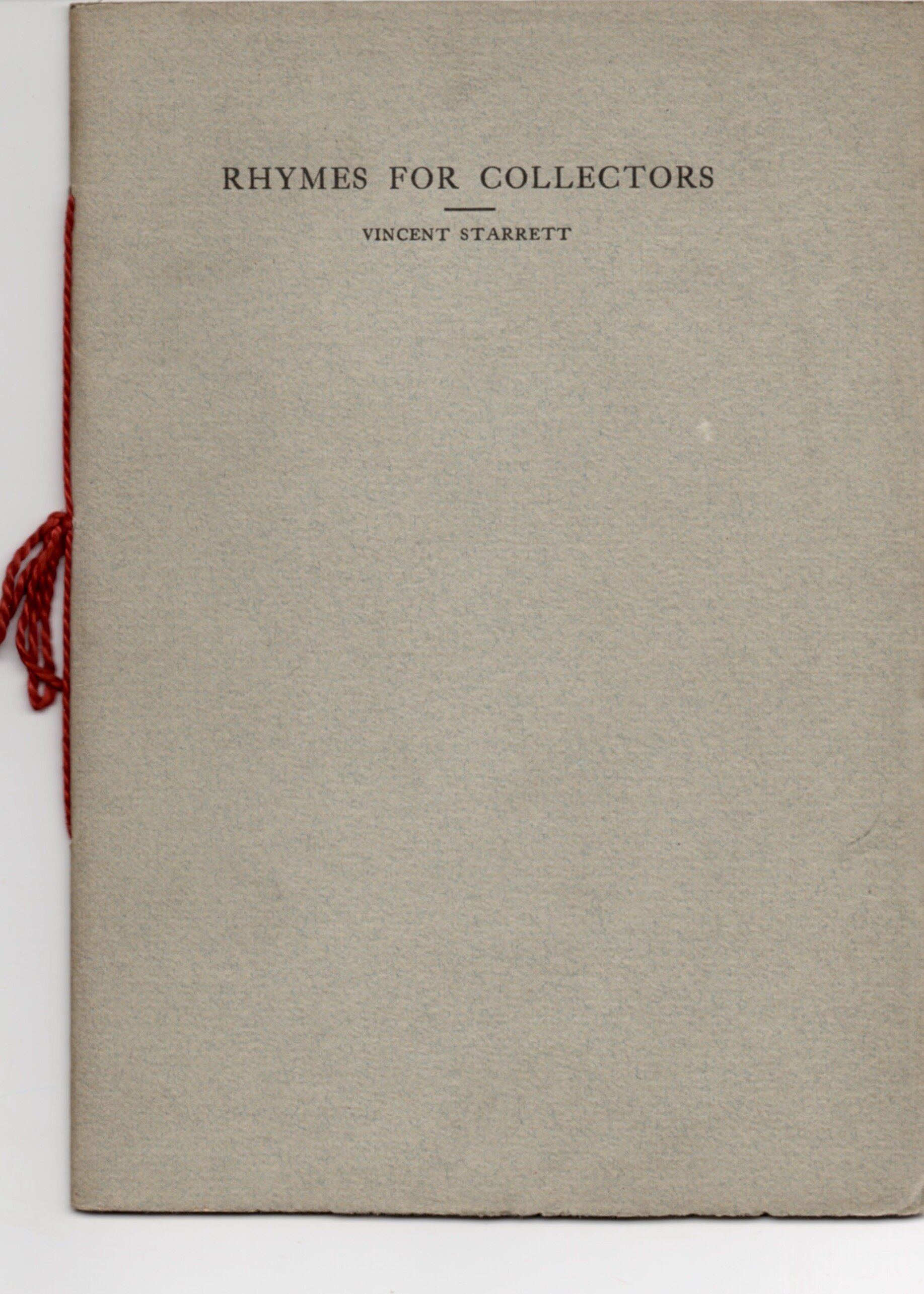

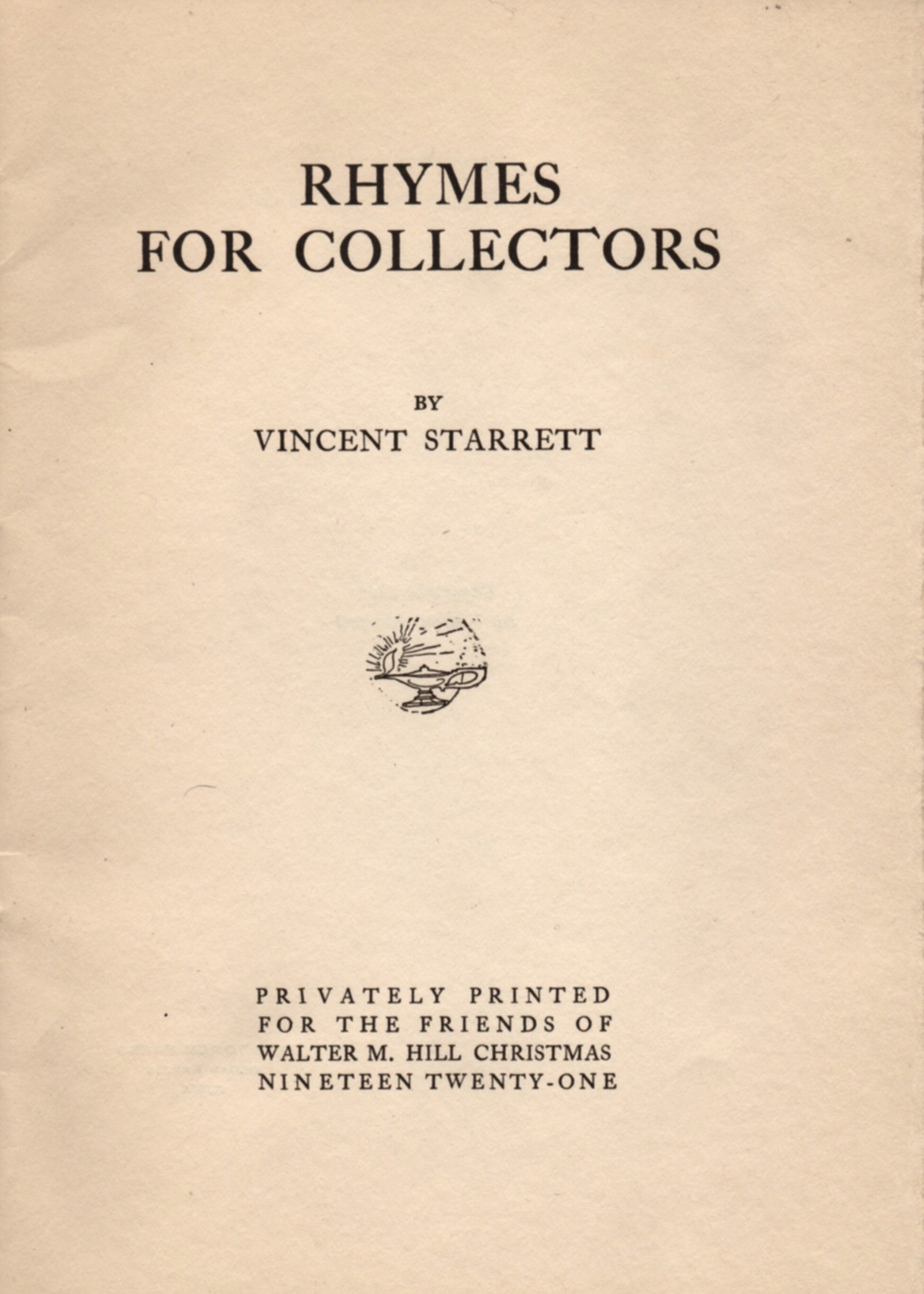

The Book: Rhymes for Collectors

Quickly we have come to my favorite set of verses. As anyone who has read “221B” knows, the combination of Starrett, books and poetry can be memorable. And here is a booklet of just 20 or so pages, with each page a tribute to some character, author or literary genre. Published by famed Chicago bookseller Walter M. Hill at Christmas, 1921, Rhymes for Collectors shows the promise that Starrett held as a bookman who shared his joy in the words of others.

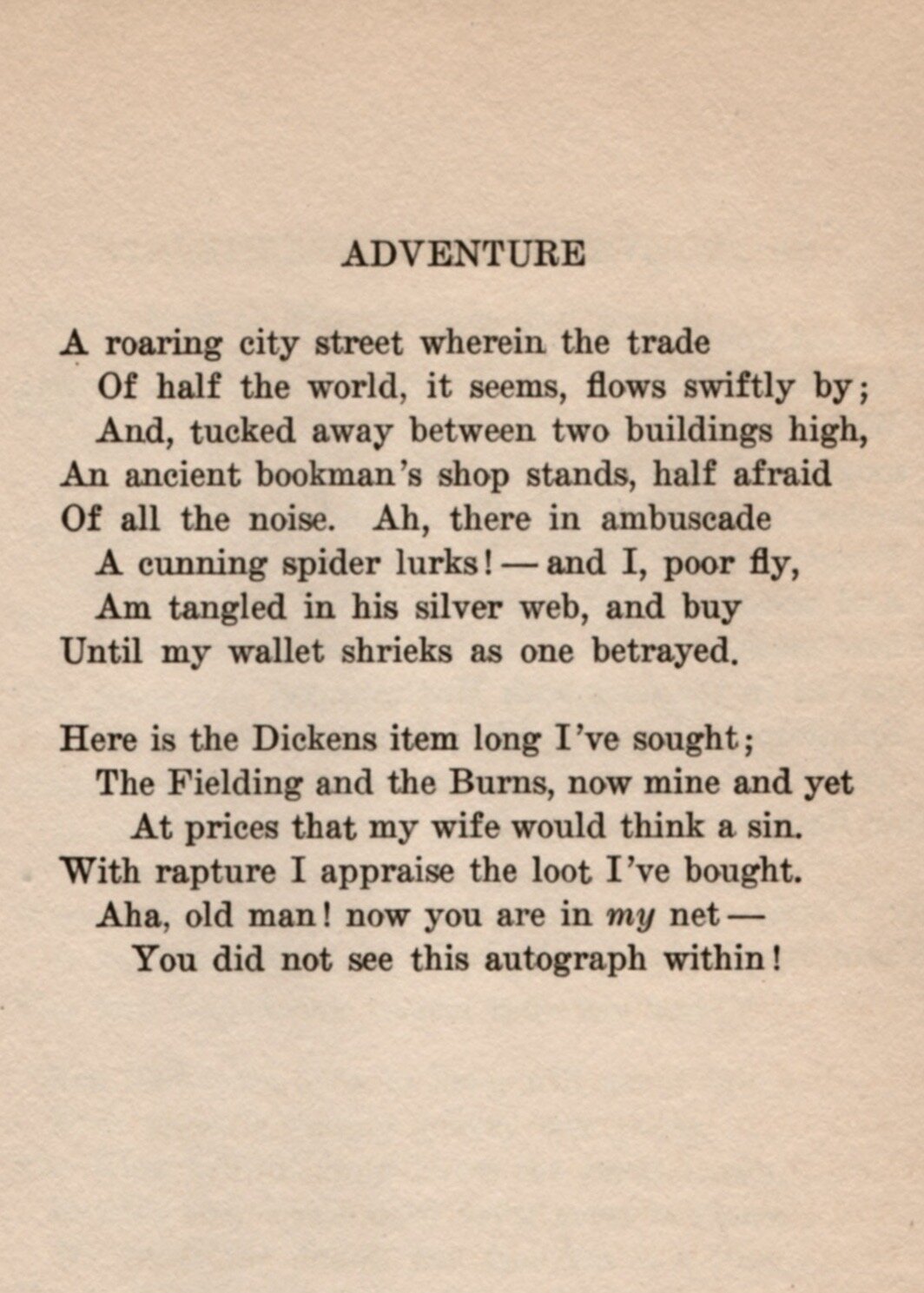

The Poem: “Adventure”

No other poem written by Vincent Starrett shows the sheer joy that comes with finding a hidden treasure on a seller’s shelf. To leave the noise of the street behind and lose yourself among the scent of decaying paper and leather bindings is to enter a world set apart. Starrett sees himself first as a spider caught by the lure of the bookshop. But in the second stanza, the tide turns! Starrett acquires (at “prices my wife would think a sin”) a volume with an autograph the dealer had not seen! An adventure in book buying indeed.

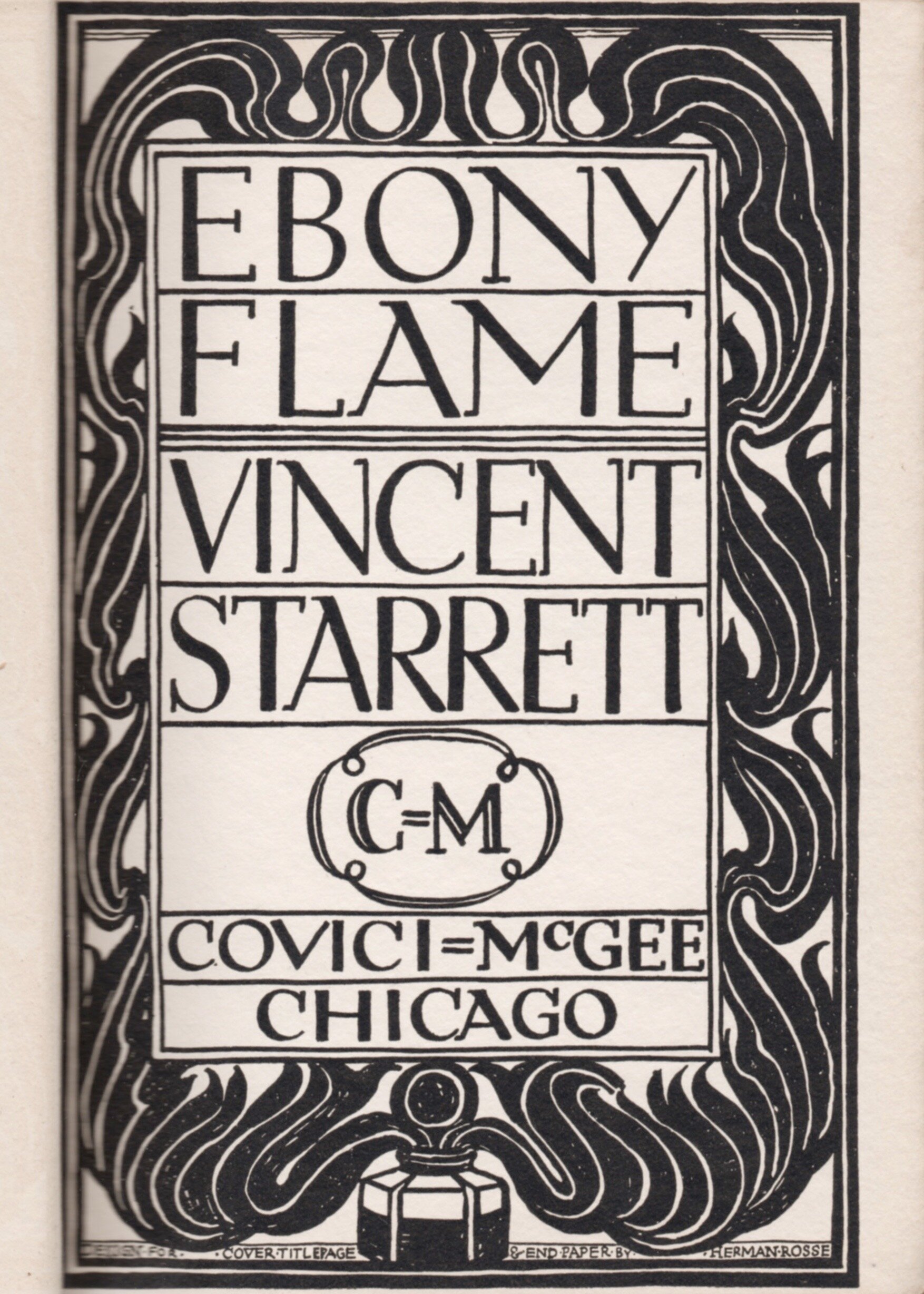

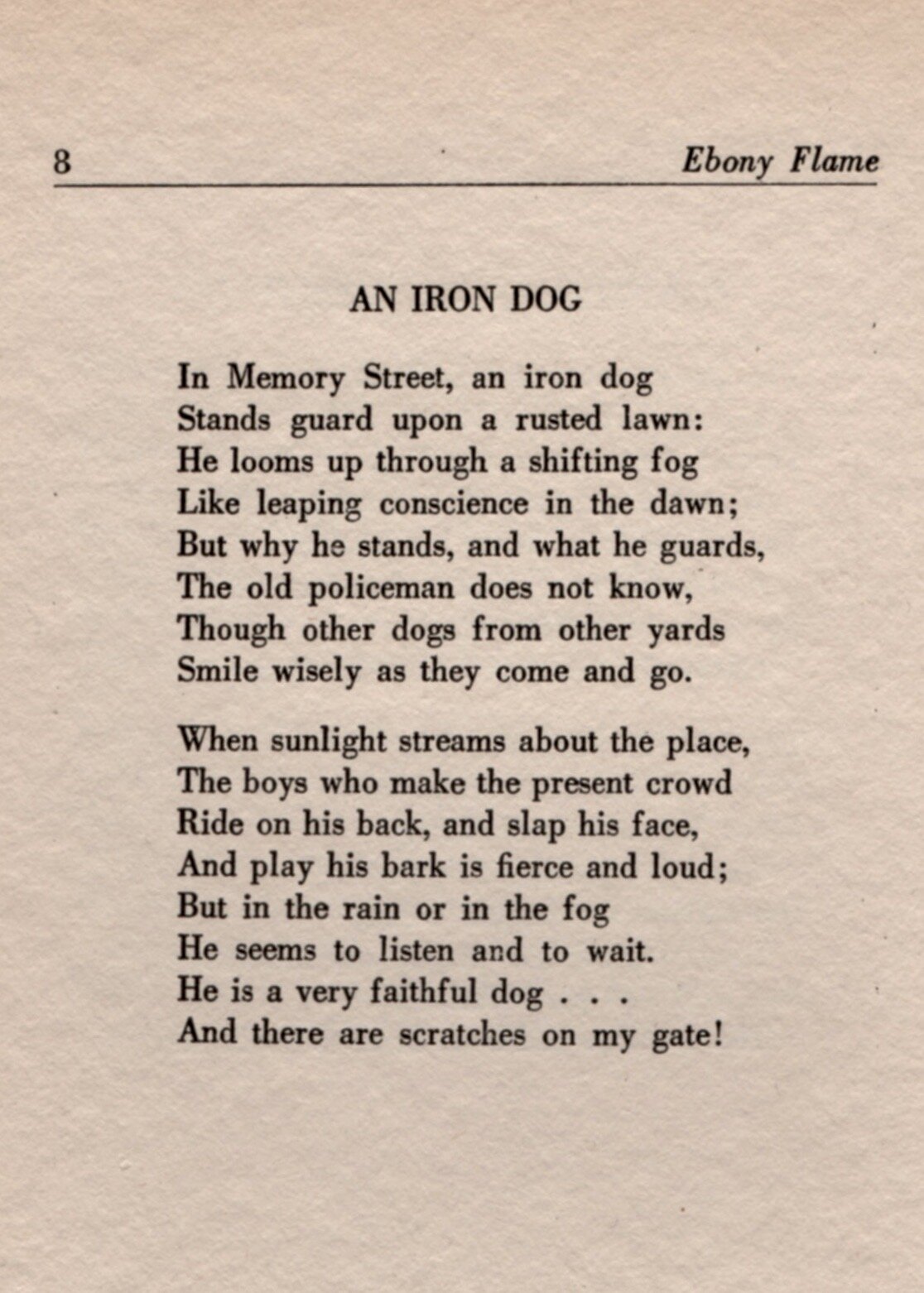

The Book: Ebony Flame

The first “proper” collection of Starrett’s poetry, published in 1922 in a handsome edition of 350 copies by Covici-McGee of Chicago. Nearly 70 pages of poetry, the slim volume collected a few of the verses that had appeared elsewhere, but much of the work is new to hard covers. I’m a sucker for the handsome title page and endpapers.

The Poem: “An Iron Dog”

Starrett’s poetry sometimes exhibited an otherworldly bent or twist in the last line, and would turn up in magazines like Weird Tales and The Smart Set. “An Iron Dog” is fine example of this idea, where the statue of a dog, clearly taken for granted by day, becomes a possible menace at night, leaving scratch marks. Oddly enough, there IS a small residential street called Memory Lane (not Memory Street) in Chicago’s Northwest Side. Was Starrett placing his verse in a real street, or is the “Memory Street” of the poem meant to evoke a lost location now found only in the mind?

The Book: Banners in the Dawn

Published by Chicago bookseller Walter M. Hill, in 1923. (A note at the back says there were 250 copies printed in November 1922.) One of the copies I own is rather special.

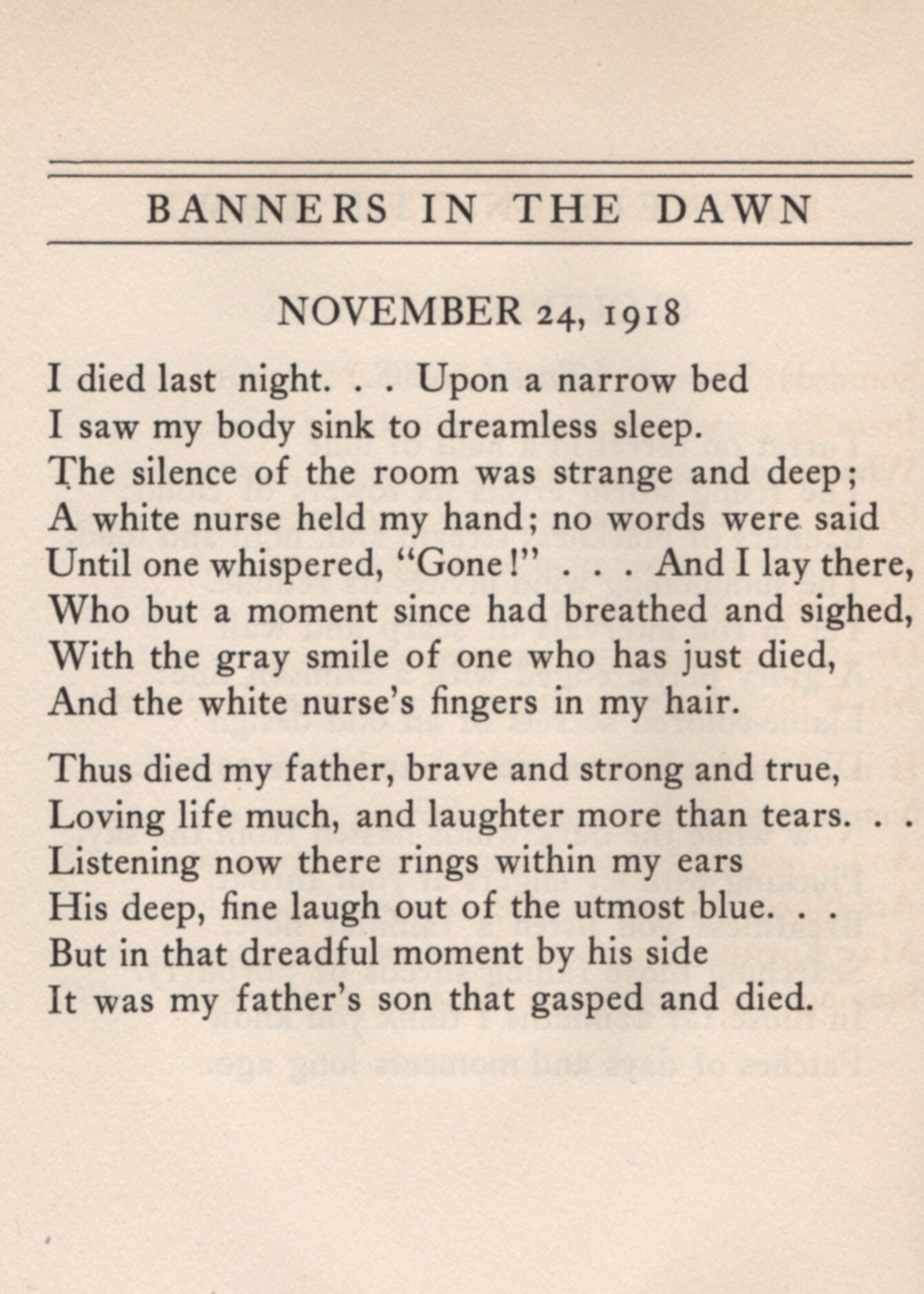

The Poem: “November 24, 1918”

Starrett’s father, Robert Polk Starrett, was a handful, according to his son. An Irishman, a bookkeeper and the kind of a guy who would pop a policeman in the nose for asking an impertinent question, Starrett saw his father’s boisterous nature as a balance to his more severe, very religious mother.

One of his last recorded memories of his father came when the elder Starrett showed up at the train station “slightly oiled” to wish Vincent good luck on his first trip to Mexico as a war correspondent. Family legend is that Robert was “slightly oiled” quite often. When his father died, Starrett was 32. His father’s death haunted him for decades.

The Book: Flame and Dust

The biggest collection of his work yet at more than 80 pages, Flame and Dust was produced by Chicago bookseller Pascal Covici in 1924 in a run of 450 copies.

Just a handful of the poems had been published in book form before. In his Starrett bibliography, Charles Honce notes the author’s later view on the verse in this anthology: “If it can be called poetry.” Honce goes on to quote from a review of the verse in The Saturday Review of Literature by poet William Rose Benét, “His verse usually has either a twinkle in its eye or is wrapped from nose to toes in the black cloak of the macabre. … His is a very entertaining mind.”

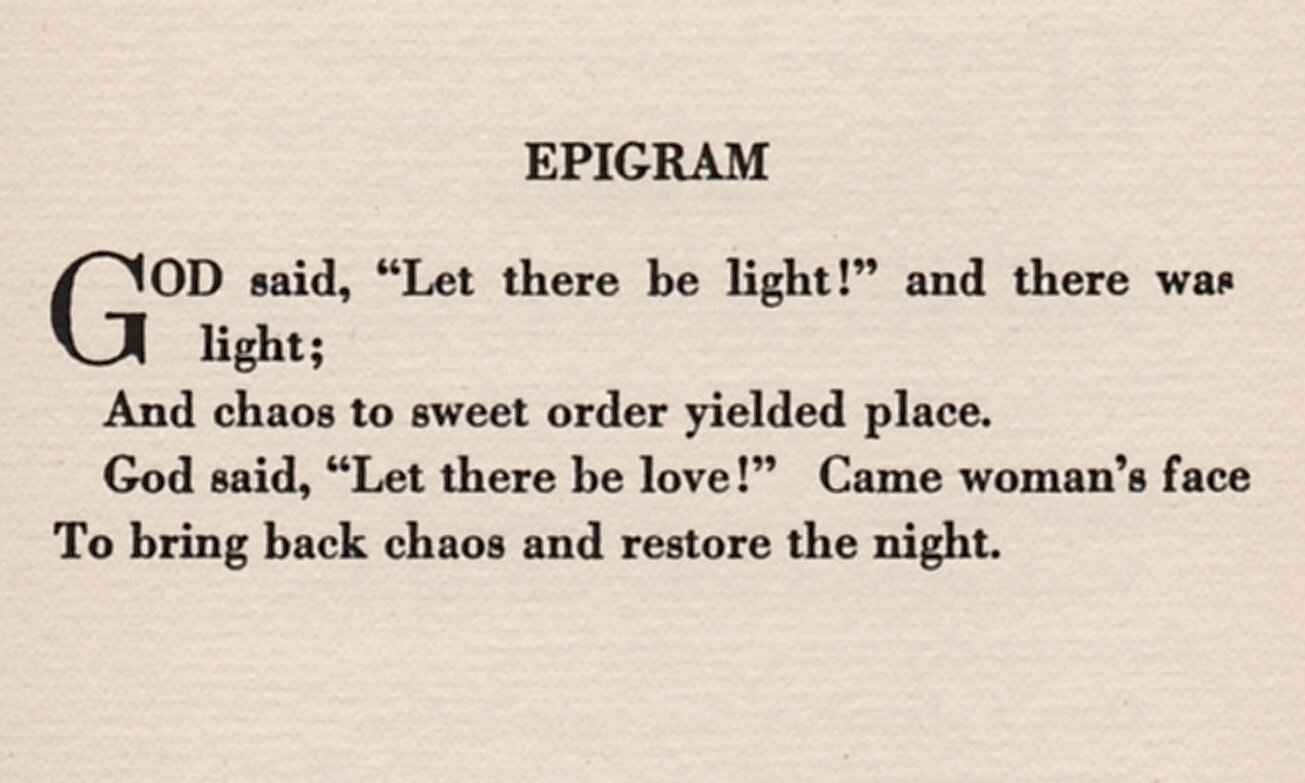

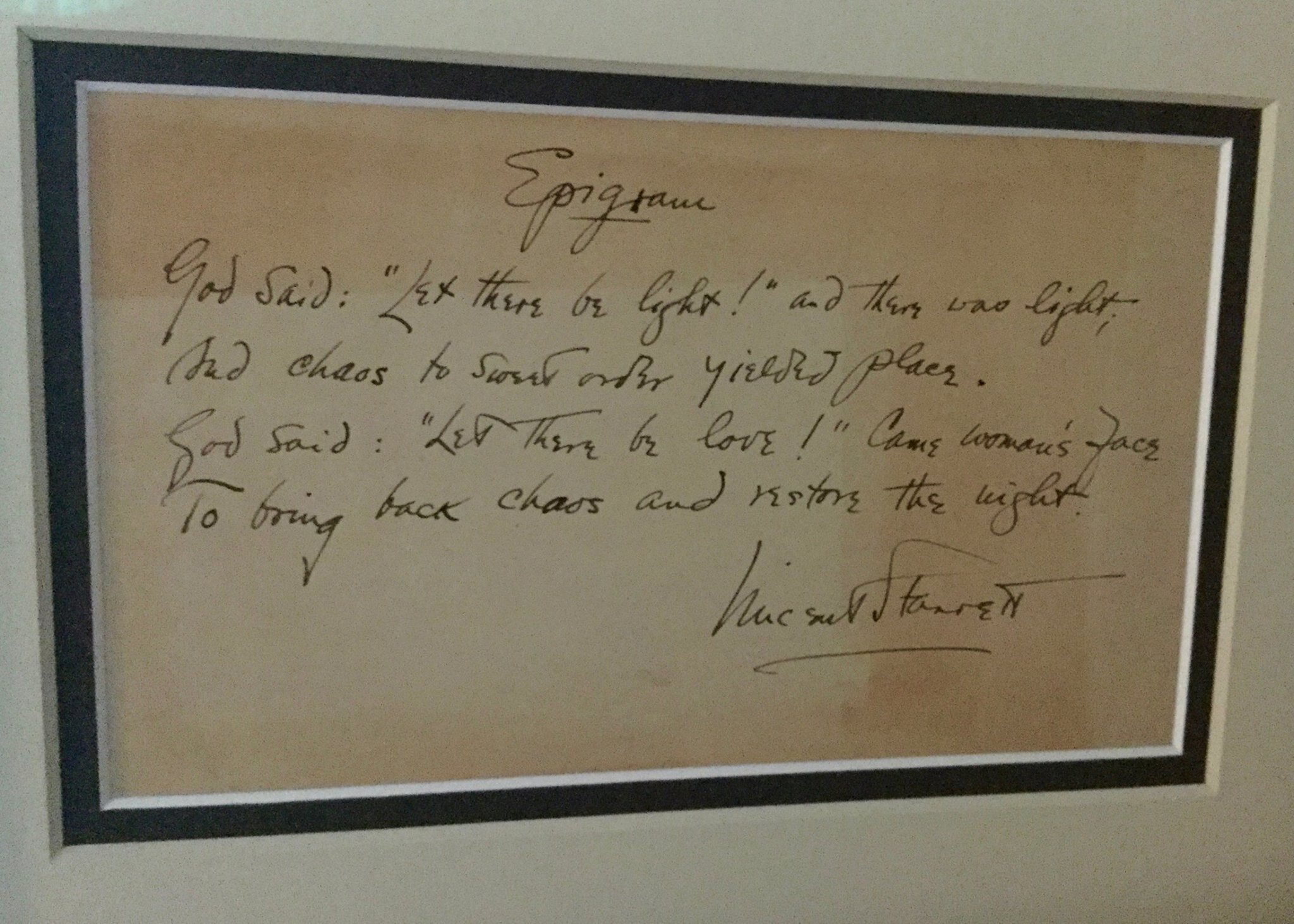

The Poem: “Epigram”

If I have my timeline right, Starrett had left his marriage to his first wife by this point. I’m not sure exactly when he met Rachel Latimer, his second wife and lifelong love, but it’s clear that women fascinated him for the way they can befuddle men. I also have to admit that I have another reason for valuing these four lines. I own them in Starrett’s own hand and they are framed on the wall behind me.

The Book: Fifteen More Poems

Published in 1927 by Edwin B. Hill, this was a humble work in colored wrappers that are almost always falling apart today. There were 110 printed, a far cry from the 450 of his previous work. Starrett told Honce: “It took E.B.H. a year to do this on his hand press—since then I have given the poor fellow only leaflets.” We will explore those leaflets later in the year.

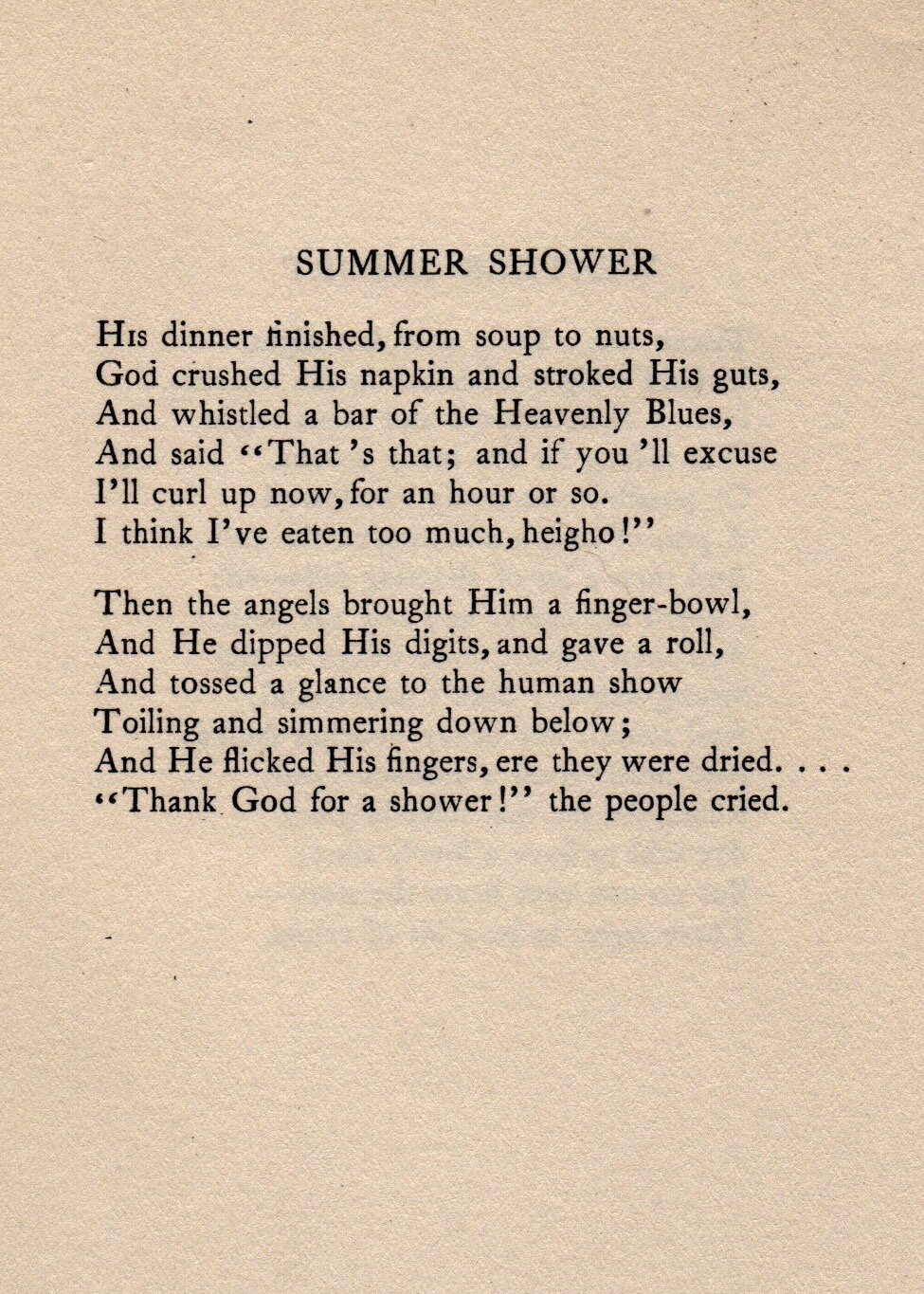

The Poem: “Summer Shower”

It seems hard to believe that anyone would have a problem with this whimsical poem in the 2020s, but in the 1920s, Starrett could not get it published. “Until now I have not been allowed to print it anywhere,” he told Honce. Times change. Times change.

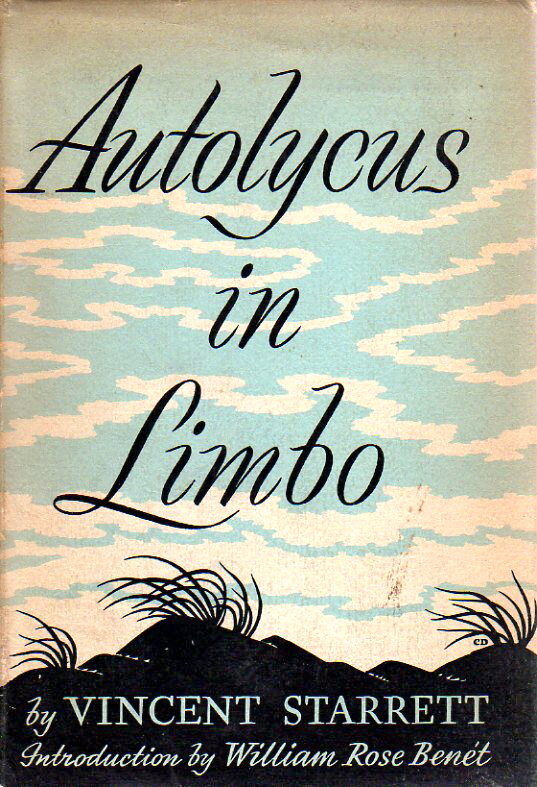

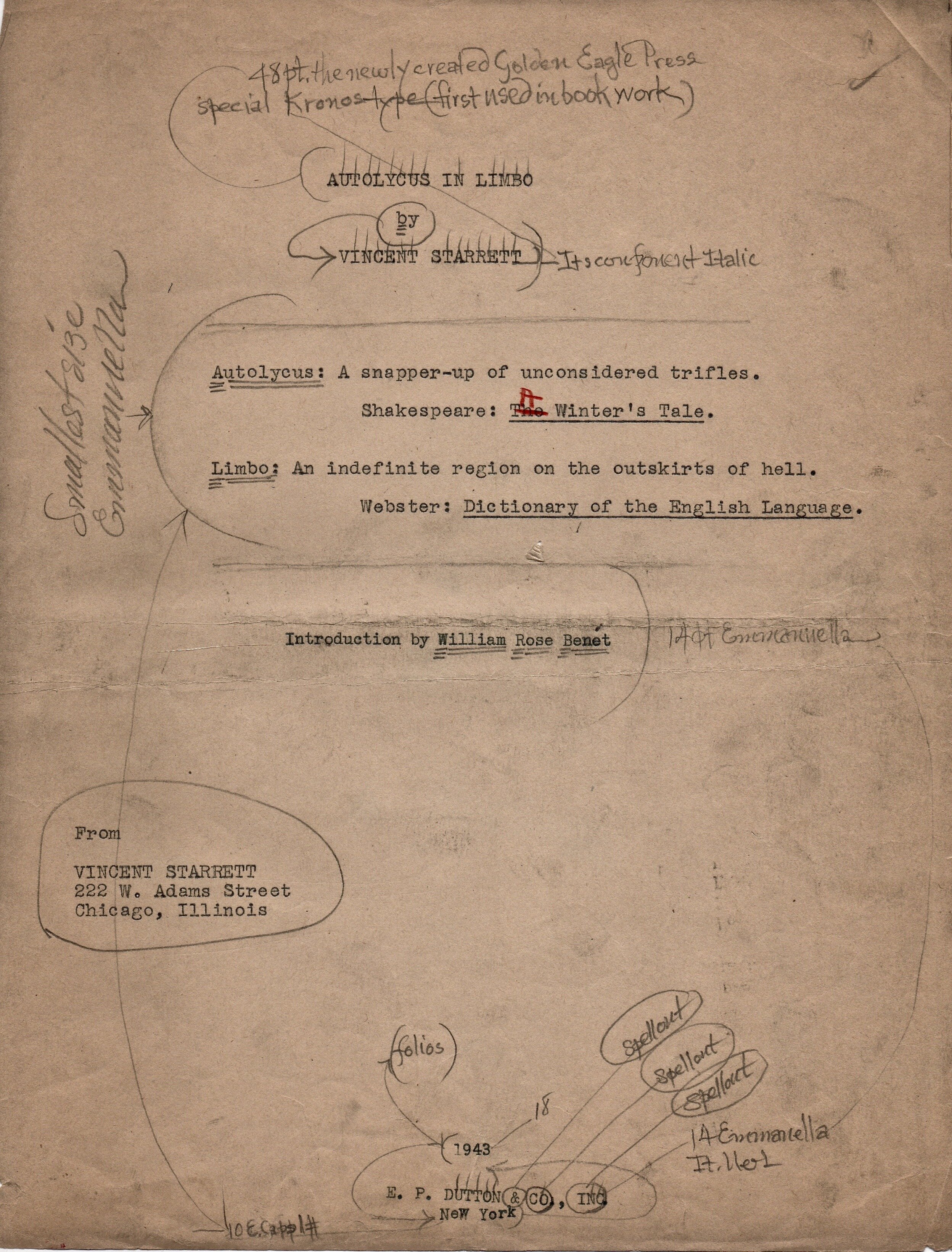

The Book: Autolycus in Limbo

Sixteen years passed until his next anthology. The world had gone through the Great Depression and World War II, and Starrett had retired from mystery writing and become a book columnist for the Chicago Tribune. No longer one of the fresh-faced boys in the post-Chicago Renaissance, Starret was well into middle age when E.P. Dutton and Company published this collection of verses in 1943. William Rose Benét, who had acknowledged Starrett’s “entertaining mind” in a review of Flame and Dust in 1924, was along for the ride writing an introduction to the current work. Here he concludes that the book, “can safely be left to the literary connoisseur.”

The Poem: “To Wicky, My Wire”

The natural selection, of course, would be “221B,” which was first published in book form here. But I’ve covered that territory already. Instead, I’ve gone with Starrett’s ode to his dog, Wicky.

Starrett wrote occasionally about animals and seems to have liked both cats and dogs, but I don't find much in his columns or memoirs about the animals in his life. Still, you get a real sense that he enjoyed his constitutionals with the little wire terrier and appreciated its company.

I like to think of him roaming the streets of his Chicago neighborhood, the dog lazily checking out each tree and wall. After all the angst-ridden verses about love, women, death and life, this simple reflection is quite touching.

The Book: Brillig.

In 1949, Starrett was 63. His creative life was now largely behind him and his future was writing about books for the Chicago Tribune. Poetry was one of his first loves, and he still dabbled in the practice from time to time, writing sonnets that would appear in the Tribune, The Step Ladder (the journal of the Bookfellows of Chicago), Living Poetry magazine and even The Baker Street Journal. The passions of his youth had cooled and now his verses were meditative and sometimes playful. There is a lot of looking back in this book, published by The Dierkes Press of Chicago. It was the last poetry anthology published in his lifetime.

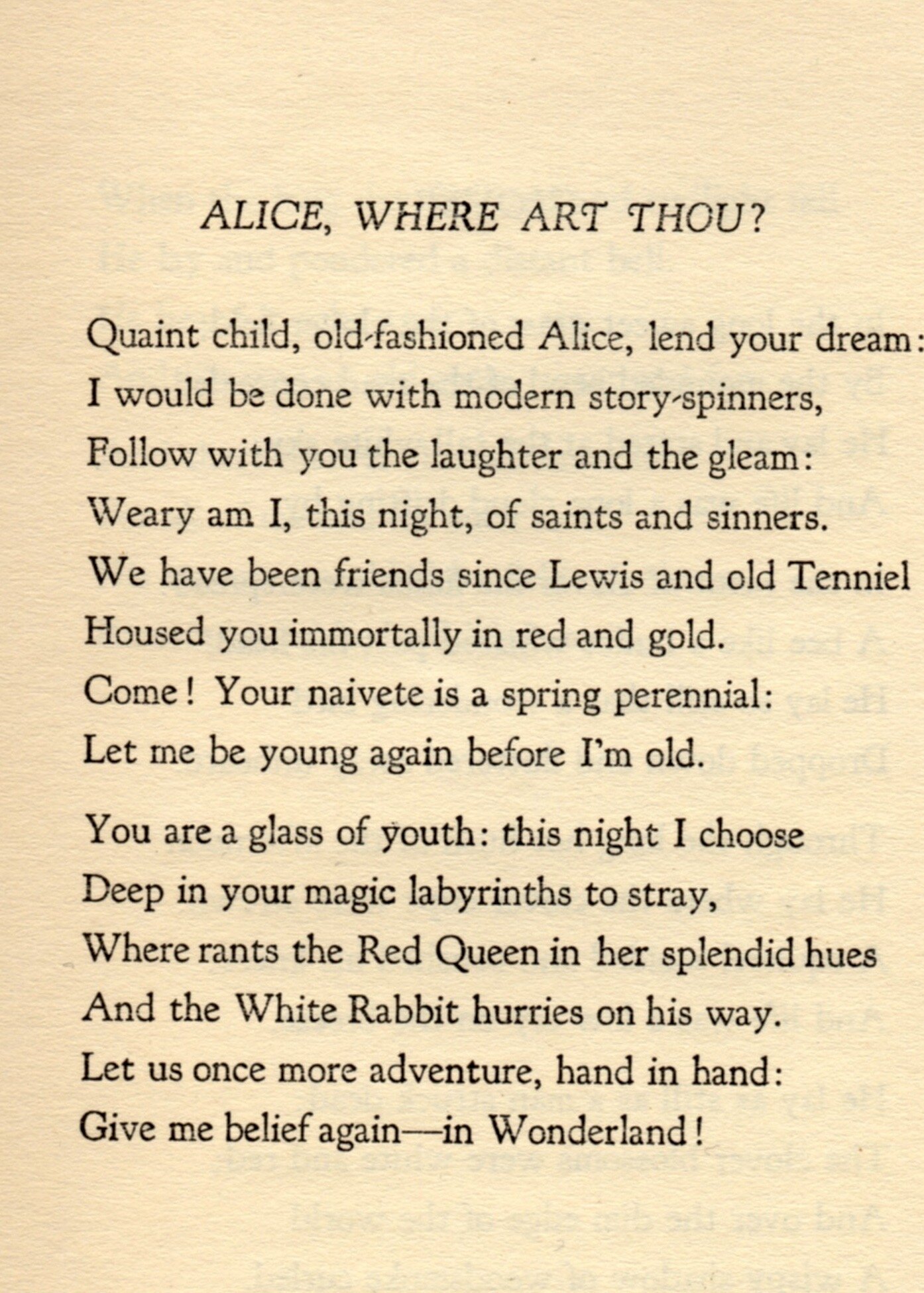

The Poem: “Alice, Where Art Thou?”

Starrett first feel in love with books in the back of his grandfather’s Toronto bookshop, where children’s classics abounded. So it’s appropriate that in his last collection of verse, he would circle back to Lewis Carroll’s tale of Alice and her adventures. “Let me be young again, before I am old” he cries, anxious to follow the young Alice one last time:

“Let us once more adventure, hand in hand:

Give me belief again—in Wonderland!”

L’envoi

So there you have it.

Was Starrett a great poet? No. But I have learned over the years that if you want to understand the man, you must also appreciate his work. For much of his creative life, poetry was the key outlet where Starrett allowed his passions to show, whether they were for women, literature or fantasy.

Or dogs.

I don’t have a picture of Wicky, but here’s a family photo of Starrett and “Princess,” taken around the time of the first World War. Princess was a police dog he later jokingly dubbed the “The Hound of the Baskervilles.”

Even with dogs, Sherlock was never far from Starrett’s mind.