"221B" fresh from Starrett's typewriter

85 of Starrett's poems, including '221B,' from his own typewriter

"During this period, Charles Honce gave my morale a lift by compiling A Vincent Starrett Library, an annotated bibliography of my published writing as of that time. Possibly it was this splurge of energy and authorship that enabled me to get my best book of poems published. For some time I had been hoping to bring out a definitive collection, and this was accomplished in 1943 with the publication by Dutton of Autolycus in Limbo, for which William Rose Benét wrote the introduction."

— Books and Bipeds, pp. 304-305

The manuscript page for the title page of Autolycus in Limbo, published in 1943 by E .P. Dutton & Co. The published title page is at the bottom of this post.

There are moments in collecting Vincent Starrett when I catch my breath and feel dizzy. That's how I felt a few days ago when I opened a package from a used and rare book dealer. (Before you ask, this was not part of the recent auction involving Don Posnansky's incredible collection. Finding out who owned this before is a mystery I'm hoping this post will help clear up. If you have some information, let me know at studiesinstarrett@comcast.net.)

Inside was a sturdy library box and, on opening that, a breathtakingly beautiful maroon binding. The spine on this hand-bound cover reads AUTOLYCUS IN LIMBO/VINCENT STARRETT/ORIGINAL TYPESCRIPT MANUSCRIPT.

And that's what it is. Take a look.

Directly from Starrett's typewriter, and collected here just as they came back from the printer, are the pages of Starrett's book of poems, including the immortal "221B."

I don't want to tease you too much, so we'll start with "221B" and work around the rest of the manuscript.

"221B" from Starrett's typewriter.

221B

There are a few things to note:

This is certainly a carbon copy. You can tell by the slightly blurry and "heavy" look to the type. Most of the poems in this collection are originals, but there are also more than a dozen carbons.

The paper for "221B" is a good grade, general use typing paper with no watermark, and has aged a bit in the intervening 75 or so years. (There is one poem that's on what we used to call "onion skin," a very thin, transparent style paper that was most often used, in my experience, for sending letters overseas.)

If this is the carbon, what happened to the original? It was most likely sent to Edgar W. Smith (see Irregular Records of the Early 40s in the Baker Street Irregular's History Series).

The dedication to Edgar W. Smith was not added later, but is part of the original, showing this was Starrett's intention all along. Smith had become a good friend of Starrett's after the two bonded over Starrett's book, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. (Again, see Irregular Records of the Early 40s.)

This is only one of two poems in the collection that has a dedication. The second, "Scottish Blood" is "For Ray," Starrett's wife Rachel."Only those things the heart believes are true." See that underline under the word "believes"? Back before there were word processors to do such things, this is how an author indicated a word should be put in italics for emphasis.

By the way, I know folks love the last line of this poem, but as I've said elsewhere, this line is it's most insightful and touching sentiment. I believe that's why it retains its impact all these many years later.Starrett typed his name at the bottom, and then crossed it out. This is true of several poems, perhaps ones he sent to periodicals for publication. Up to this point, "221B" had only been published privately as a holiday card for Christmas 1942 and then in the pages of the Chicago Tribune on Jan. 1, 1943.

Starrett dates the poem "March, 1942". He more specifically dated it March 11, 1942 in the holiday card.

At the top right of each poem is a number, which served in lieu of page numbers for the book. This sonnet's number started as 30, was edited to 31 in red ink (perhaps by an editor at Dutton or a production person at The Golden Eagle Press), but was in fact the 32nd poem in the collection. You'll understand why in a bit.

At some point, the poem's title and dedication were moved to the same line. Take a look at the poem as it appeared in the printed book.

Autolycus in Limbo was the first time "221B" was published in hard covers and the sonnet would reach its widest distribution so far. The poem slowly grew in popularity over the following decades. Starrett's Chicago branch of the Baker Street Irregulars, The Hounds of the Baskerville (sic), would take it up and recite it annually, and other Holmes groups around the nation would soon start doing the same.

"221B" as it appeared in Autolycus in Limbo.

Other Items of Interest

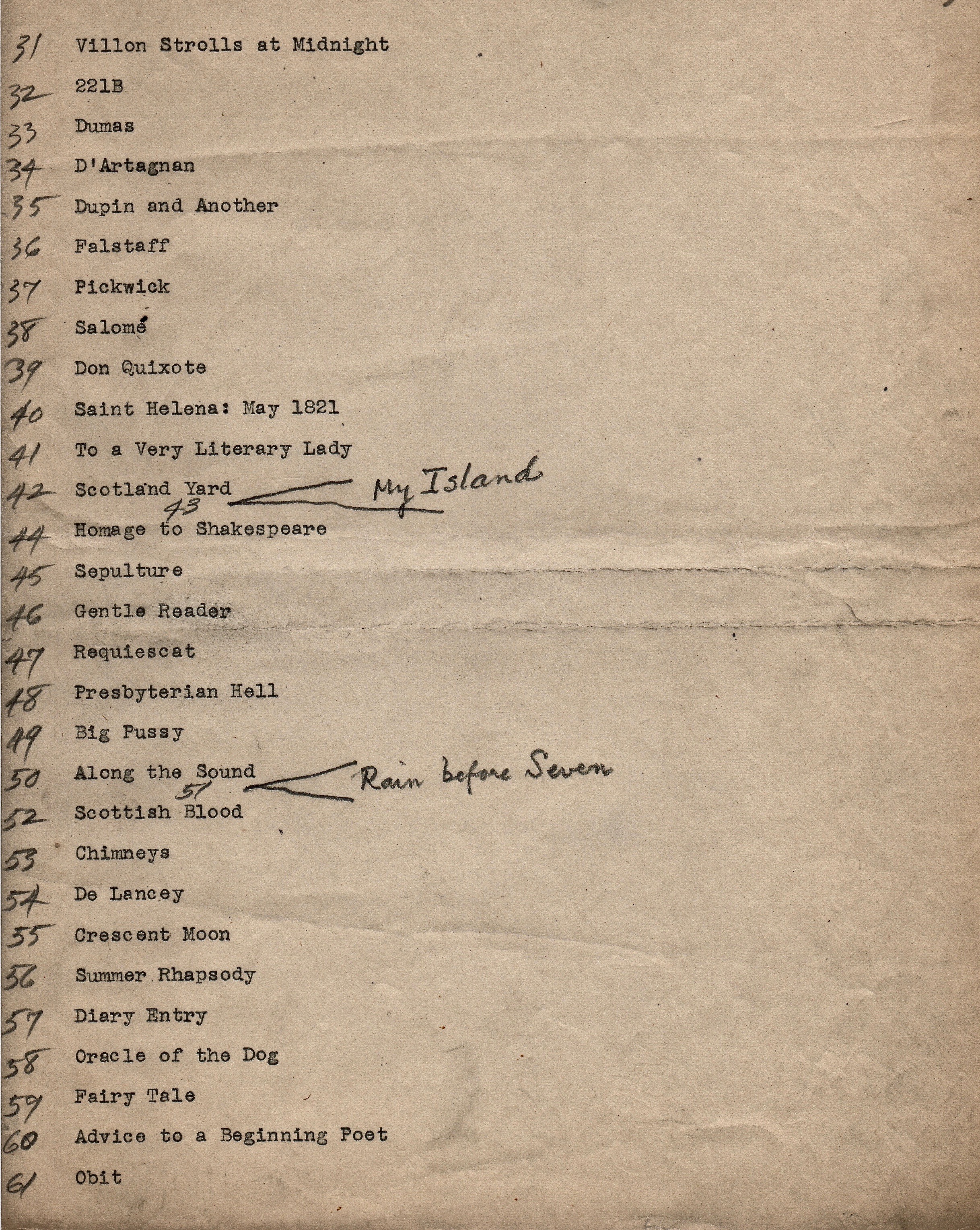

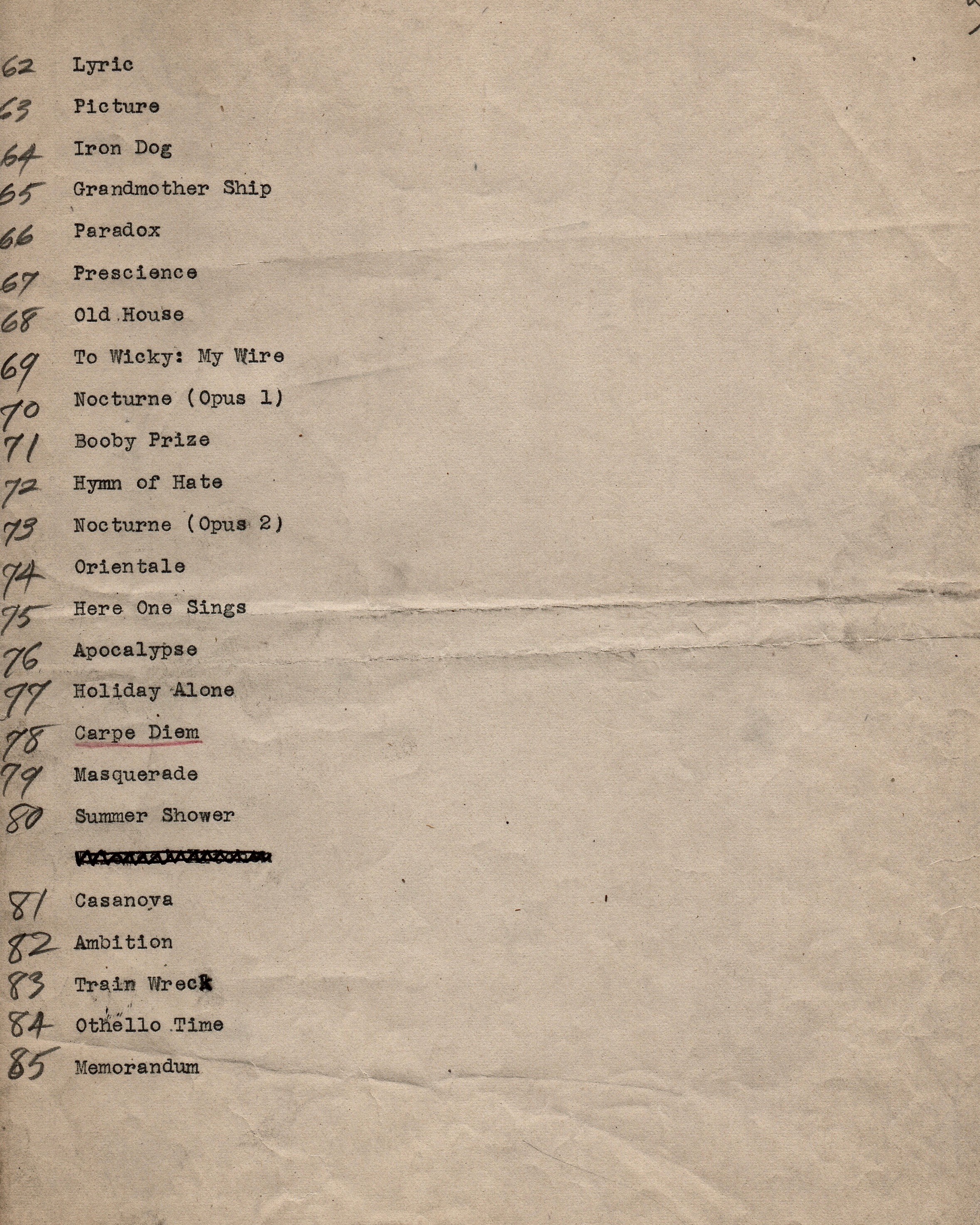

The list of poems to be included in the volume clearly evolved as the book was being put together. This list of poems was supposed to be three pages long, but it went to a fourth page.

Also notice that new poems were slipped in, pushing the numbering off. That's why "221B" went from No. 30 to 32.

Starrett's hand written insertion note was later marked out.

The poems in manuscript carry only occasional notations in Starrett's hand. Here's one.

The note at the top reads, "Insert after Hell, Said the Duchess, probably as p. 10."

In other places, he makes small spelling corrections, like "prey" for the incorrect "pray" in the poem "Cherchez la Femme."

In the poem, "Self Portrait," he has added a note that says, "Circa 1920." In fact, the poem was first published in 1923 in one of his first books of poetry, Banners in the Dawn.

For the most part, Starrett's poems are pretty clean and he doesn't make many changes.

The letter

There is one other item of interest in this impressive historical document: A letter from Starrett to the printer, Sam A. Jacobs, at The Golden Eagle Press in Mount Vernon, New York. (A very informative essay on Jacobs—who had a long association with E.E. Cummings—and his press is available at the American History Printing Association's website.)

Starrett starts the letter by talking about a book that was printed by The Golden Eagle Press for his friend and bibliographer, Charles Honce. The book, The Public Papers of a Bibliomaniac, was published in a very limited run and is difficult to acquire today. The book has an essay in it about Stephen Crane's early works. Both Honce and Starrett were Crane fans and campaigned to have the late-Victorian era writer recognized as a truely original American voice.

Starrett had published a bibliographical study of Crane in 1923. Now, he was working with Ames W. Williams on an expanded and updated bibliography and wanted to include details about Honce's book. Why Starrett didn't ask Honce for this information isn't clear. And it seems that Starrett did own the book ("It's a lovely book, as are all your books.") but perhaps didn't trust himself in making these bibliographical judgments.

At any rate, he tells Jacobs that was "much pleased" with the look of Autolycus in Limbo. Comparing the manuscript with the final version helps to understand just why Starrett was pleased. It's a very handsome book. There were 1,500 copies published and copies are pretty easy to find these days.

As promised

I've taken longer than usual to work through this manuscript, but I hope you'll agree it was worth the time.

As many of you know, lately I've been obsessed with "standing over Starrett's shoulder" to see how he did his work, and this is one of those ways in which we can watch him do just that.

And now, as promised, we'll close with the handsome title page as it appeared in print.

Compare this with the manuscript version above.

The chat and comment feature here is not the easiest to use. Until I find a more welcoming format, I invite you to discuss this and other Starrett-related topics at the Studies in Starrett Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/VincentStarrett/

See you there.