'So They Still Live For All That Love Them Well'

Chapter 2: Before there was '221B', there was TPLOSH

A section of page 93 from the first edition of Starrett’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, published in New York by The Macmillan Company in 1933.

The literature of Sherlock Holmes

We don’t know exactly when Starrett started collecting Sherlockiana. Chances are he started picking up odds and ends as a teen-ager. We do know that by 1917 (when he was 31), Starrett wrote to the editor of The Bookman looking for a copy of an article on Conan Doyle:

“I’m trying to collect, as faithfully as may be, the ‘literature of Sherlock Holmes’ who is my favorite character in light fiction, and altogether a delightful creation.”

(See Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle & The Bookman, edited and annotated by S.E. Dahlinger and Leslie S. Klinger, Indianapolis: Gasogene Books, p. 262.)

It was in 1918 when Starrett wrote a review of His Last Bow, for the now-obscure Reedy’s Mirror. Rather than review the value of the tales, he began his first foray into canonical inquiry. It would not be his last.

In 1920, Starrett wrote his first full Sherlock Holmes piece, “The Adventure of the Unique Hamlet,” a pastiche intended more to tweak fellow bibliophiles than to entertain other Holmesians. In fact, in those pre-Baker Street Irregulars days, it’s doubtful if Starrett even knew of many others who shared his devotion to the “delightful creation” that was Sherlock Holmes.

What is certain is that he collected Holmes literature with a passion that could only come from a deep respect for the literature.

By the late 1920s, Starrett boasted that he owned one of the best Holmes collections in the world. For Starrett, the question was this: Could he use his collection to create a memorable and permanent contribution to the literature of Sherlock Holmes, that would at the same time, finally make him a world-recognized author? The answer came in 1930 with the death of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

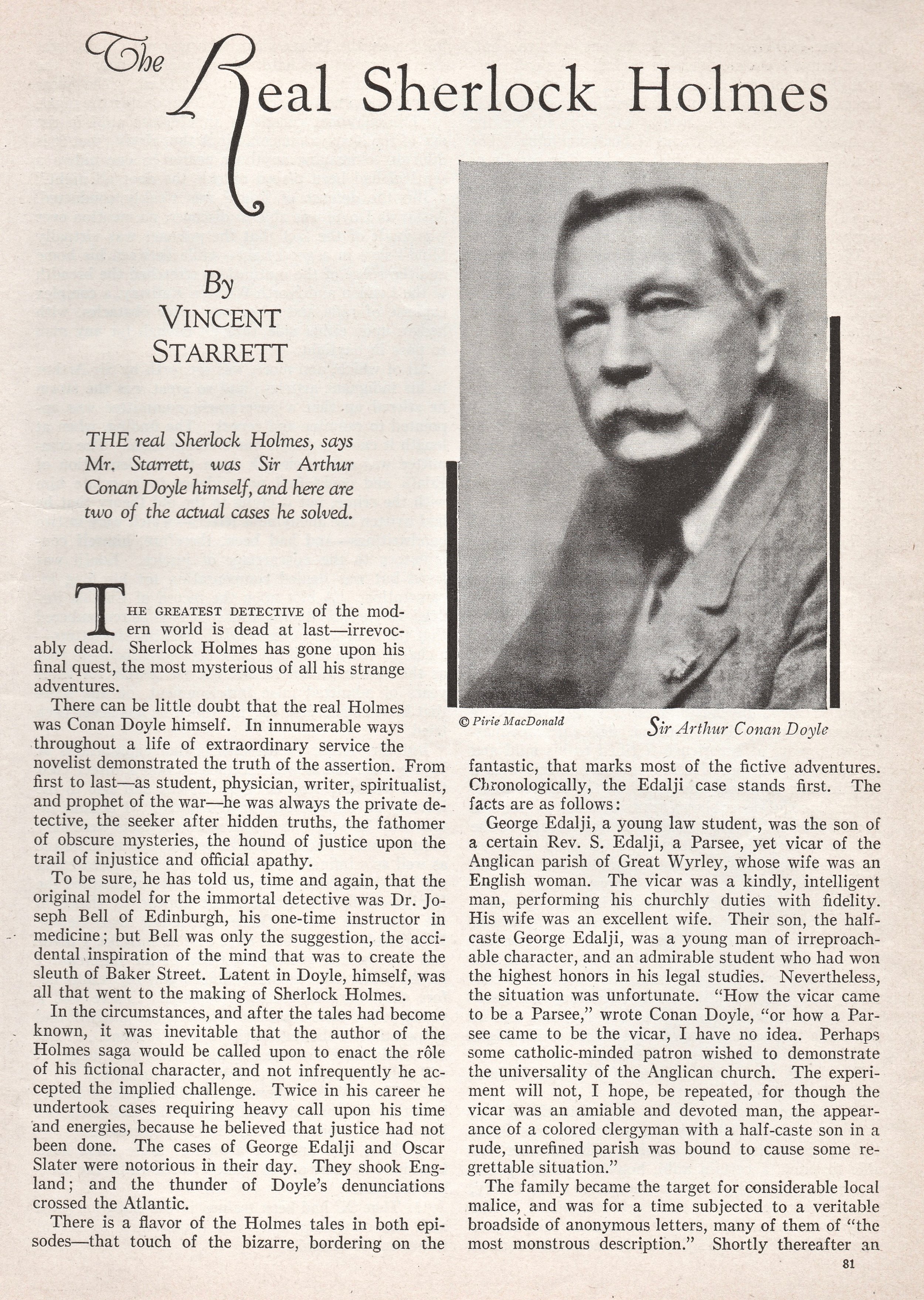

Starrett wrote a magazine article for the December 1930 issue of The Golden Book magazine entitled “The Real Sherlock Holmes” about the life of Sir Arthur, focusing on his passion for justice and detective work as illustrated in the George Edalji and Oscar Slater cases. The article had what is known in the news business as “legs.” Reader’s Digest picked it up for its January 1931 edition and editors expressed interest in more of the same.

Starrett was now convinced that he could produce a series of essays about Holmes, put them together into one volume, and produce a best seller.

‘No. 221-B Baker Street’

Cover to the first edition of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, 1933.

Three years later, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was published in the United States, making it the first book in this country dedicated solely to Holmes and kicking off the Sherlock Holmes movement in this country.

It is also where one can find the seeds of the poem “221B”.

In the book’s fourth chapter, titled “No. 221-B Baker Street,” Starrett recounts the adventures of Dr. Gray Chandler Briggs, who made an important discovery while walking down Baker Street in the early 1930s. Walking in the footsteps of Col. Sebastian Moran, Briggs entered the second story of Camden House and looking out found himself staring at No. 111 Baker Street, which he concluded was the true 221B.

Briggs wrote to Starrett about the discovery, which delighted the Chicago bookman. For Starrett, Sherlock Holmes and 221B were inseparable. The fact that you could walk down Baker Street and point to a house and say, with tongue firmly planted, “That’s 221B” was a sheer delight.

As Starrett wrote in Private Life:

“If there be one yet living who doubts the reality of these wraiths, let him write to the Central Post Office in London, and ascertain how many hundreds of letters have been received, during the last quarter of a century, addressed to Mr. Sherlock Holmes at 221-B Baker Street – a man who never lived, and a house that never existed.”

Proto-’221B’

But The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes has a more direct relationship to Starrett’s sonnet. In the last paragraph of the book’s title chapter are a few lines that will be instantly familiar. It’s written in prose, but reads like poetry:

“But there can be no grave for Sherlock Holmes or Watson … Shall they not always live on Baker Street? Are they not there this instant, as one writes? … Outside, the hansoms rattle through the rain, and Moriarty plans his latest devilry. Within, the sea-coal flames upon the hearth, and Holmes and Watson take their well-won ease … So they still live for all that love them well: in a romantic chamber of the heart: in a nostalgic country of the mind: where it is always 1895.”

A calendar printed by the Sherlock Holmes Society of London in 1963, an analog year to 1895. 2019, the year this was posted, is another 1895 analog.

A bookmark that captures the sentiment of Starrett’s prose poem.

When Elmer Davis (who would go on to write the Constitution and Buy-Laws of the Baker Street Irregulars) reviewed TPLOSH for The Saturday Review of Literature he used the occasion to expound on the many and various trifles that had been investigated (and are are still the subject of debate) by early Holmes scholars. But when it came to this heartfelt sentiment, Davis could do nothing more than reprint those final lines.

It’s a moving and unforgettable passage.

Everything that Starrett wrote about Sherlock Holmes in this book is condensed here: the nostalgia for a bygone era, the cozy serenity of Baker Street, the enduring friendship between Holmes and Watson, and the evil machinations outside the window that offer both the threat of a deadly challenge and the promise of thrilling adventure.

For a Depression-era book, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes sold well enough to have a small second printing in the United States along with a British edition, both in 1934.

And yet, Starrett was disappointed. While it is considered a classic today, sales of Private Life were not as strong as Starrett wanted.

Once again, Starrett’s hopes for literary immortality faded.

While there was no reason for Starrett to make the connection, it is interesting to note that The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was published in 1933 – the same year that a young Adolph Hitler was elected Chancellor in Germany. Reality was about to invade the peace of Baker Street, as you will read in Chapter 3.

‘221B’ Chapter Index

Chapter 1: Introduction and Prologue: ‘Where it is always 1895’

Chapter 2: 'So they still live for all that love them well'

Chapter 3: ‘Some of the most dramatic months… of contemporary history’

Chapter 4: ‘Here dwell together still’

Chapter 5: ‘He has done many little things for me’

Chapter 6: ‘A wider circulation’

Chapter 7: ‘Part of a slim volume’

Chapter 8: ‘This poem by my good friend’

Chapter 9: ‘Something remains of London in 1895’

Chapter 10: What is it we love about ‘221B’?

Chapter 11: Afterthoughts and Acknowledgments

Want to chat about this blogpost? Join us at the Studies in Starrett Facebook page: