The Complete Publication History of 'The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes'

Private Life Chapter 1: The challenge is made and we begin our journey

And we’re back. Hope you had a good summer and arrive here tanned, rested and ready to leap headfirst down the Vincent Starrett rabbit hole, because that’s we are headed.

A shelf of Sherlock: The publication history of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes on one shelf.

This autumn, we’re going to do something a little different. Most of the blog posts I’ve done so far feature recent purchases or are attempts to connect differing Starrett works together to show the breadth of his work or the single-mindedness of his book-buying passion. I’m going to set that format aside.

For the next several weeks, we’re going to look at just one title: The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. When it was published, there was nothing else quite like it in the United States. Over the years, it’s been reprinted, rewrapped, unbound, updated, and translated. Like Watson’s experience of women, the book has been experienced over three continents. And while it’s no longer in print, old copies do a brisk business on the resale market.

If you own just one Starrett work, you need to own this one. It's that important.

I figure it will take us the better part of the next three months to thoroughly examine why.

A few notes before we begin:

Don't expect bombshell revelations. In fact, each article will be more like knitting things together that have been printed elsewhere, occasionally by me, but often by others. Starrett recycled bits and pieces of previous works to create Private Life. I’m going to follow his lead.

This is going to be a leisurely trip. For example, it won't be until the third installment that we get to the actual first book edition. Kick off your shoes, grab a drink and relax.

I hope to have a new posting each week. That's a pretty demanding schedule for someone who does this in between everything else, but I'm going to give it a shot.

The one period I will not be discussing in depth is the pre-publication correspondence between Starrett and St. Louis physician Gray Chandler Briggs. That has been covered most ably in "Dear Starrett—"/ "Dear Briggs—" (Edited by John Nieminski & Jon L. Lellenberg and published in New York by The Baker Street Irregulars, copyright 1989.) The book is out of print, but copies come up for sale on eBay and at various bookshops, so keep your eyes open. It’s worth hunting down. As a substitute, let me recommend the relevant chapters in Mattias Bostrom's authoritative From Holmes to Sherlock (New York: The Mysterious Press, 2017 and soon available in an updated paperback edition.)

You don’t need to own each of the various editions and states to enjoy the posts. But it doesn’t hurt. So why not follow along at home and hunt down the missing works to fill up that gap on your shelf.

And with that, please walk over to that seemingly bottomless rabbit hole and dive right in.

Pre-publication: 1918 to 1930

The seed to Private Life was planted in this article.

Where does an idea come from? For Private Life, the seed was already planted by the time the Feb. 22, 1918 issue of Reedy’s Mirror was published. Starrett was a stripling at 23, but already was exhibiting a love for Sherlock Holmes as he wrote a review of the short story collection, His Last Bow.

“The advent of a new Sherlock Holmes book is a distinct literary event. Heaven alone knows how many millions of people from China to Peru breathe a delighted sigh at the word and hasten off to purchase the volume. It is very probable that Sherlock Holmes is the most popular single character in contemporary fiction; certainly he is the only one who has passed into the language, as it were; whose name has become a symbol by which all of his type and tribe are known.”

Starrett knew Holmes had climbed out of the pages of the Strand magazine and become something more.

“He is the transcendental detective par excellence; an authentic figure in the world’s literature; a genuine and artistic creation.”

He lamented Arthur Conan Doyle’s threat to put Holmes out to pasture, when there were so many stories yet to be written. In fact, Starrett sets out to name all of the adventures Watson has alluded to, but not yet given to an adoring public. And if this is the end?

The cover to Reedy's Mirror

"Let us hope there will be more, some day; but, if not, let us be grateful that we have had as many as we have, and that Sherlock Holmes is 'still alive and well, though somewhat crippled by occasional attacks of rheumatism.' "

Even as Starrett writes about Holmes, with tongue firmly planted, he was weaving a nostalgic web around the Baker Street detective, made up of memory and childhood longing. Ever the collector, Starrett imagines a time when the trifling monographs written by Mr. Holmes would become available as tangible evidence of Holmes’ reality.

“As a book lover, and a collector, I am eager to collect the works of Mr. Sherlock Holmes. In my library … I want to place those little brochures on crime to which Holmes refers so carelessly, yet so often.”

Starrett might not have been able to lay hands on Holmes’ monographs on tobacco ash or footprints, but he was amassing a collection of first editions, plus folders full of articles that had been written about Holmes by those who, like Starrett, playfully treated the Baker Street adventures as history, not fiction.

Starrett's view of Sherlock Holmes remained firmly planted in his view that Holmes was "a genuine and artistic creation." Everything he wrote for the next 50 years about Holmes started here.

Starrett also kept track of Conan Doyle’s exploits in using Holmes’ techniques to help innocent men clear their names after being wrongfully accused. The two most famous cases were those involving the unjust prosecutions of Oscar Slater and George Edalji. The press followed Sir Arthur's exploits, reminding their readers that the famous creator of Sherlock Holmes was bringing his vast knowledge and imagination to the aid of Slater and Edalji.

Starrett gathered these stories into file folders as part of his growing Sherlock Holmes collection.

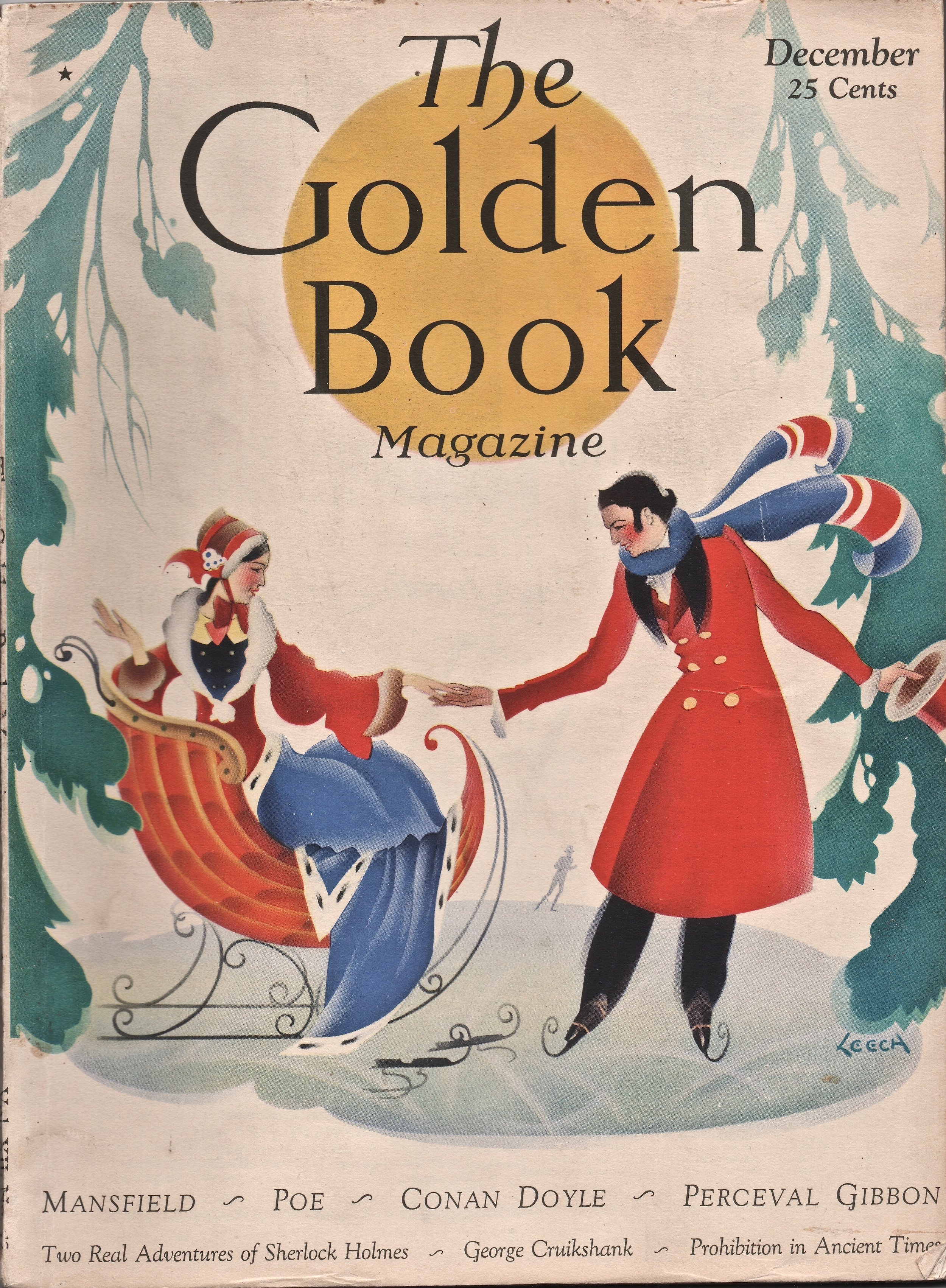

When Sir Arthur passed beyond the veil in 1930, Starrett wrote a piece for the December issue of The Golden Book magazine called “The Real Sherlock Holmes.” Starrett echoed the reporters before him and drew parallels between the creator and his creation.

"There can be little doubt that the real Holmes was Conan Doyle himself," asserted Starrett. "In innumerable ways throughout a life of extraordinary service the novelist demonstrated the truth of the assertion. From first to last—as student, physician, writer, spiritualist, and prophet of the war—he was always the private detective, the seeker after hidden truths, the fathomer of obscure mysteries, he was the hound of justice upon the trail of injustice and official apathy."

The article proved to be a hit, and an idea grew for something grander: Not just a magazine article about Holmes, but a series of related articles that could be published as a book and sold alongside the original stories.

Starrett went back to his file folders and started to organize them.

Next time: A String of Pearls.