Sherlockiana: The little leaflets at the start of a movement

Finding Bliss in Ysleta, Part 2

In our previous entry, we talked about Edwin B. Hill, his hand printing press and the friendship that grew between him and Vincent Starrett from the 1920s through the ‘40s.

Cornelis Helling made this hand-lettered folder for his set of Sherlockiana leaflets printed by Hill at Starrett’s request. In addition to Holmes, Helling was also an avid Jules Verne aficionado.

In the early stages of their partnership, Starrett selected obscure verses or bits of essays by well-known writers to be printed by Hill. A big change took place after the publication of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in 1933, when Starrett became—with Christopher Morley—the centers of the nascent Sherlockian universe in the United States.

Starrett began getting fan mail and making friends with others who enjoyed Holmes as much as he did. So it was natural for him to shift his perspective and add odd bits of Sherlockiana for his new group of Holmes friends.

That group grew slowly. Those early leaflets had a total print run of 30 or so copies. The very small print runs meant these little items were in high demand as the years rolled by. They are very hard to find today.

We’re going to look at the Sherlockiana series in chronological order, with occasional notes offered by Starrett’s biblographer, Charles Honce, or by John Myers Myers, whose checklist of Hill brochures is very useful.

I should note that several of the copies I own came from the collection of Cornelis Helling, who befriended Starrett in the 1930s. Helling got them directly from Starrett or from other dealers. You will sometimes see a brief note from Starrett to Helling.

Here they are in order, as best as can be determined.

Sherlockiana: Monody on the Death of Sherlock Holmes by E.E. Kellett. March, 1934.

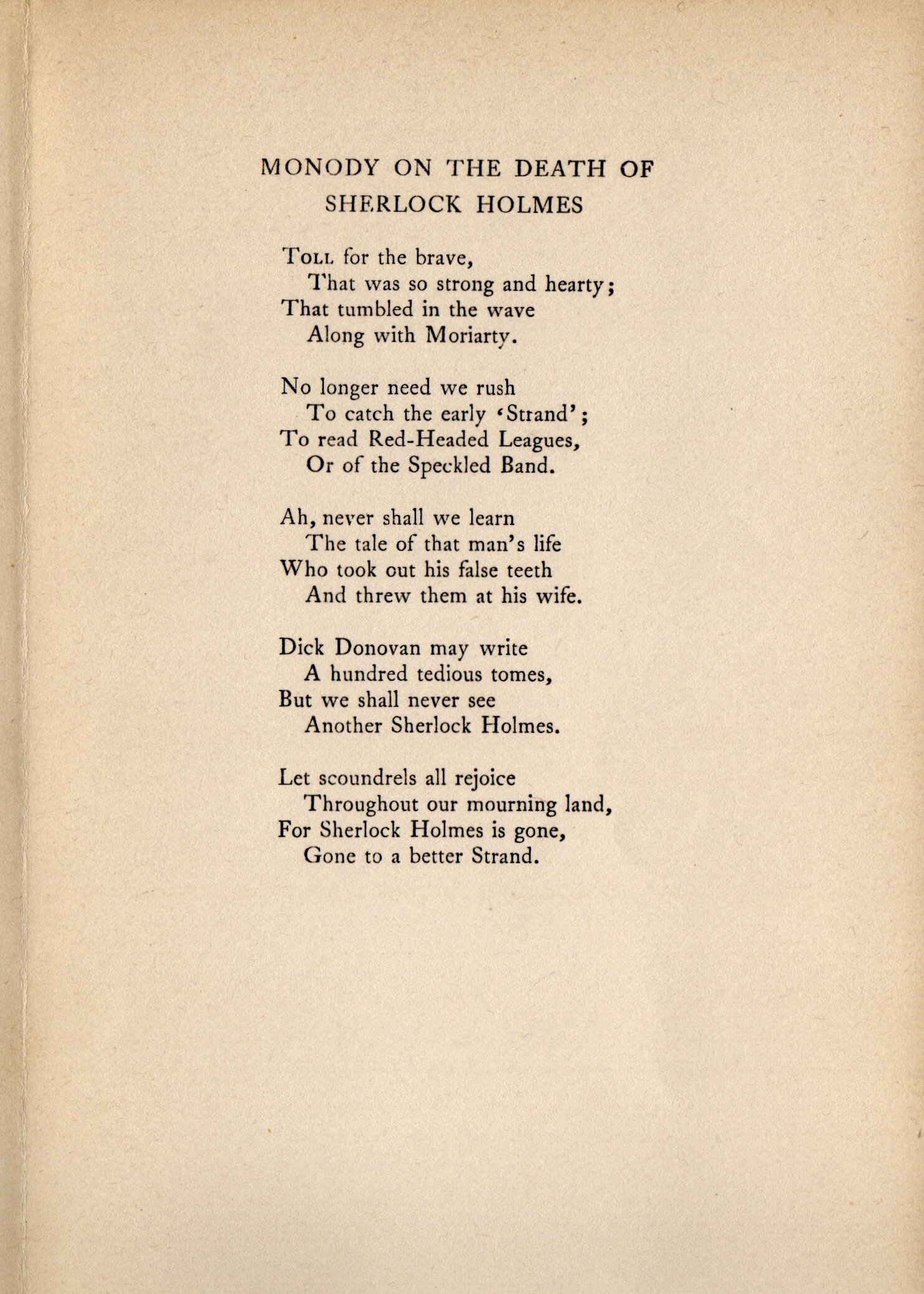

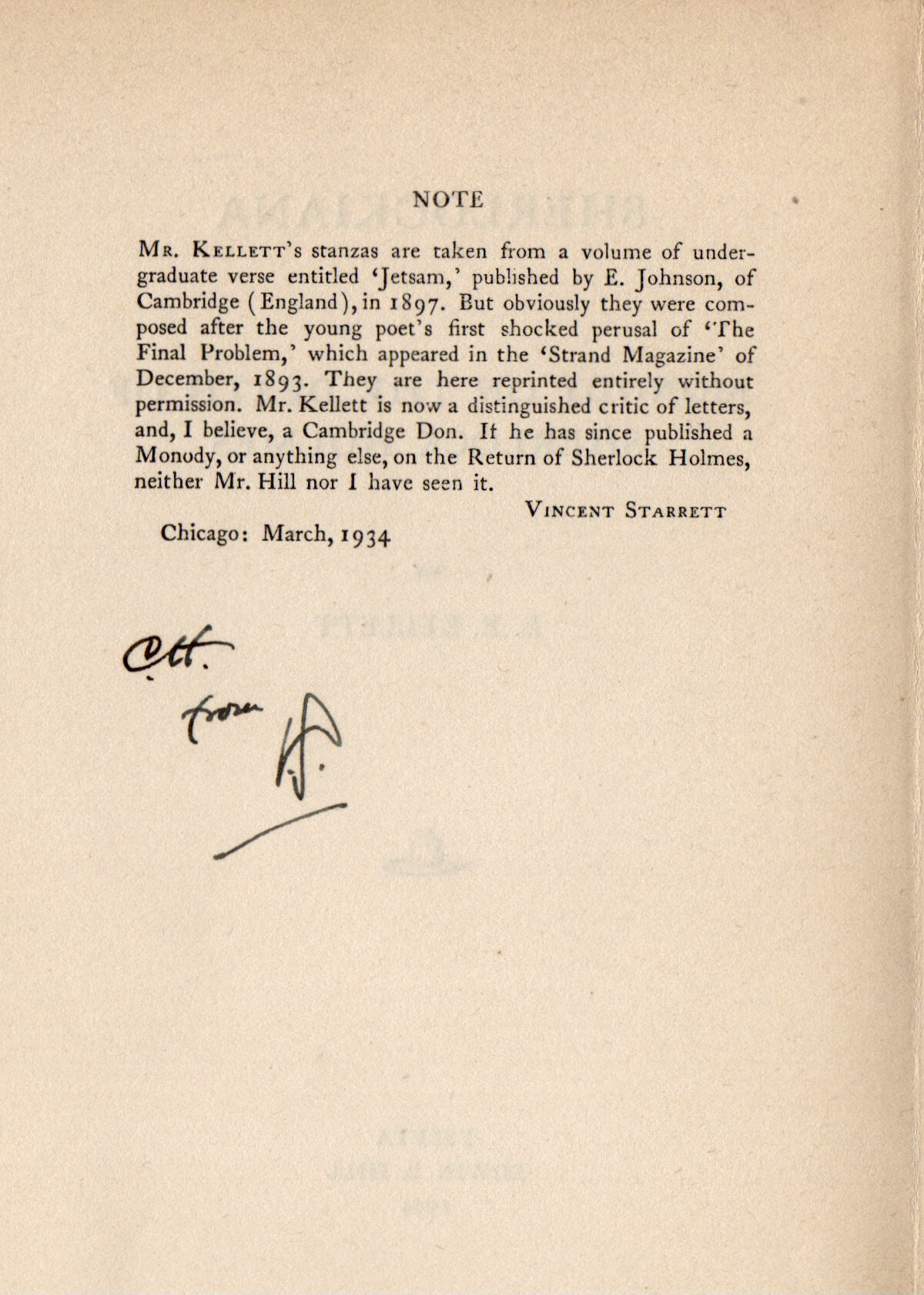

Like Ronald Knox’s “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes,” Kellett’s essay was a college student’s effort. It was written shortly after “The Final Problem” was published and Sherlock Holmes was thought to be dead. It originally appeared in an volume of undergraduate Cambridge verse entitled Jetsam.

Starrett’s note cheekily says Monody was published without the author’s knowledge or permission. Only 30 copies were run off.

The leaflet also sets the standard for most of the Sherlockian-related leaflets to come from Hill and Starrett. One sheet of paper, folded in four, with a cover, either one or two pages of copy, and a limitations page. The limitations page often included additional background information explaining why Starrett selected this item to reprint.

You probably know this but I had to look it up: A monody is a poem lamenting someone’s death.

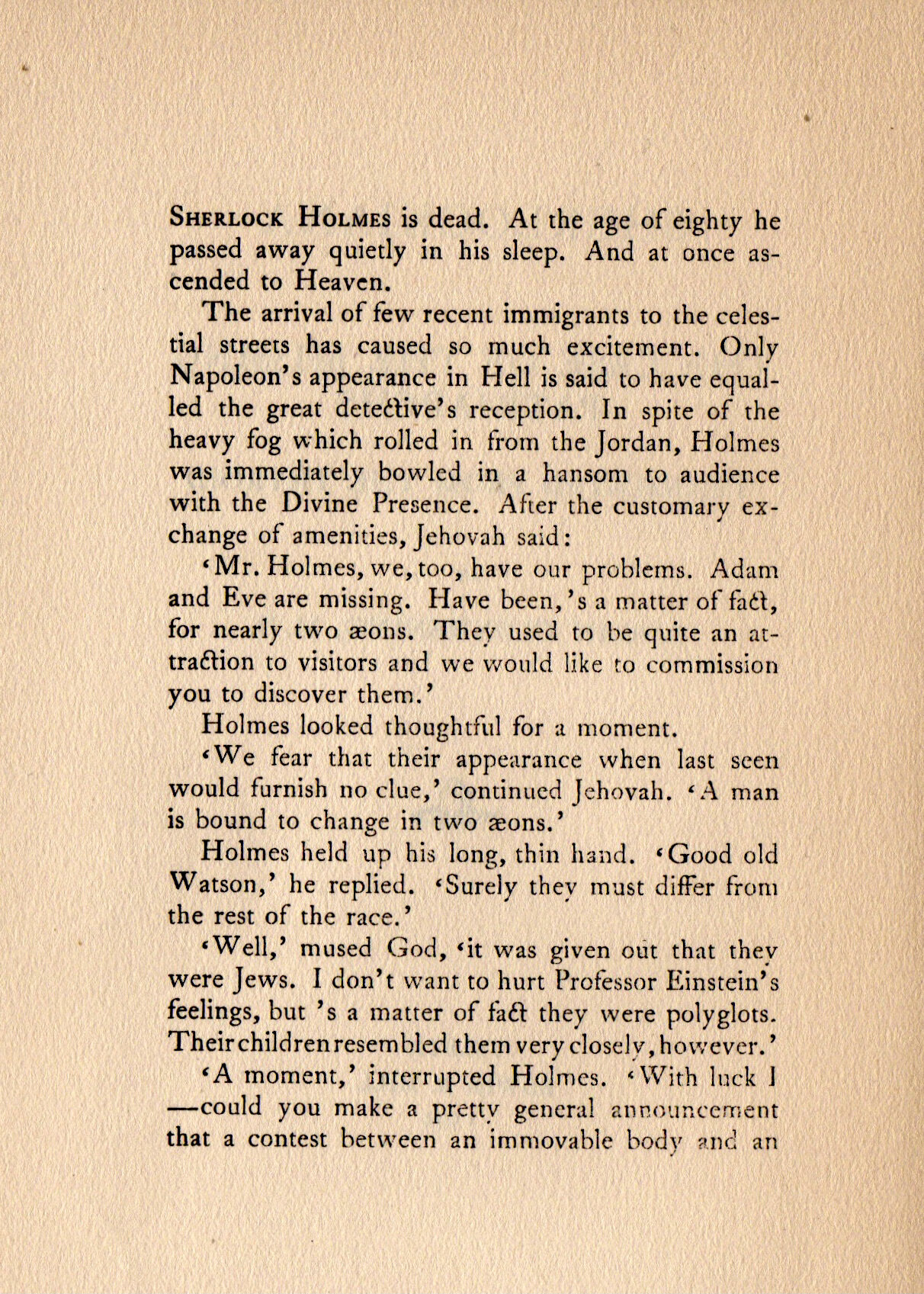

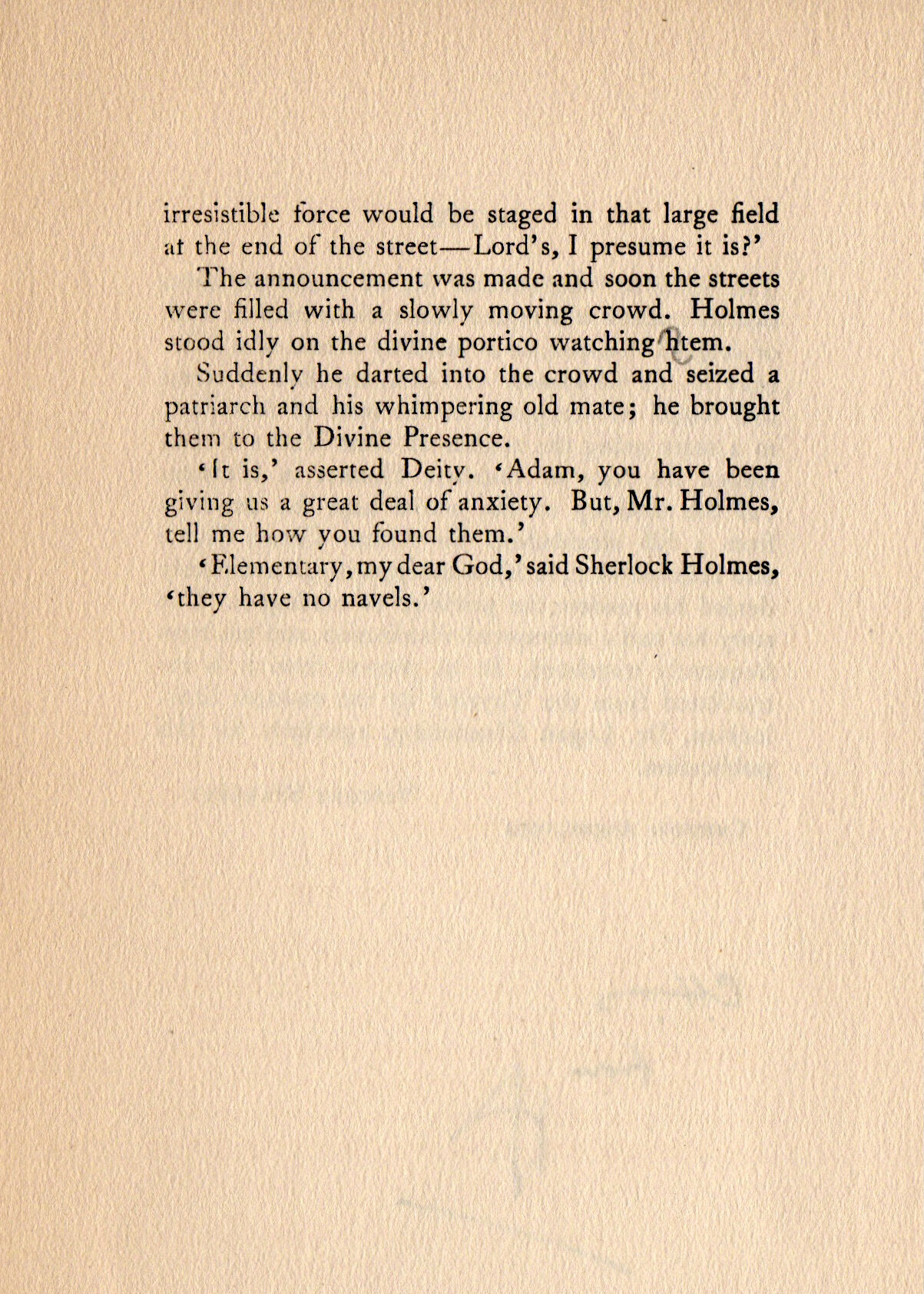

Sherlockiana: The Case of the Missing Patriarchs, Translated from the Thyroid by Logan Clendening, MD. August, 1934.

Just five months after Monody, Hill produced this four-page leaflet, again in a limited run of 30 copies.

It tells the familiar joke about Holmes being consulted by the Almighty, who needs the Great Detective’s abilities to locate Adam and Eve. The two have been misplaced, and even though the Almighty is the Almighty, He needs Holmes’ help.

Starrett acknowledges this was already a well-worn chestnut in 1934, but it was winningly told by Dr. Clendening, so deserved publication.

In the 1930s and 40s, Clendening was to popular medicine what CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta is for today’s audiences. He was also a dedicated scholar in many topics, from Shakespeare to Sherlock. Clendening inspired one of the best-known examples of selfless giving in the Sherlockian world. You can read about it here.

Sherlockiana: Three Poems by Vincent Starrett. 1934.

In the same year, Hill published three of Starrett’s poems under the Sherlockiana label, even though their association with Holmes is sometimes tangential There is no month noted on the leaflet, and neither Honce nor Myers Myers cite anything other than the year. As a result, we don’t know if it came before, between or after the two items already cited.

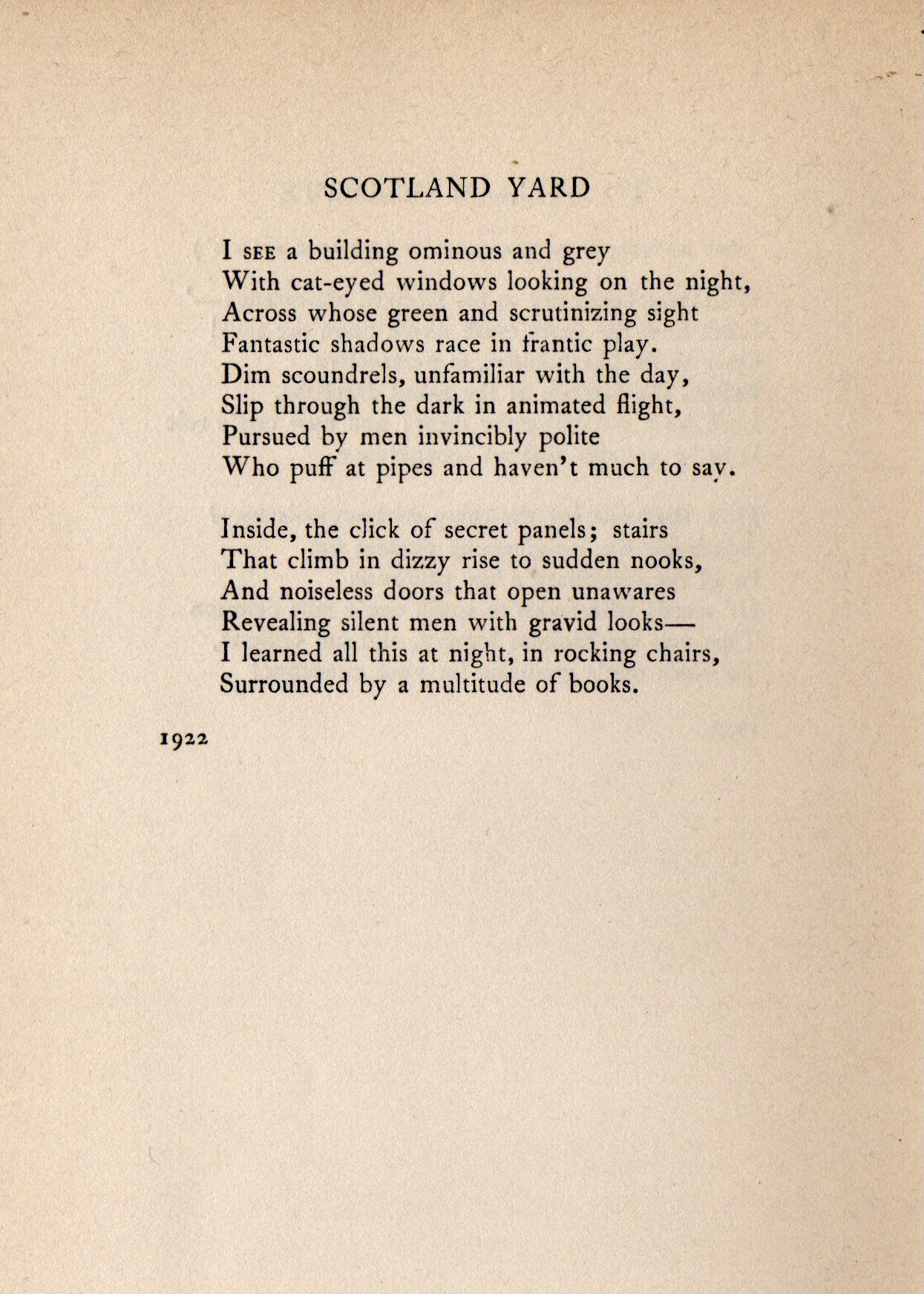

Of the three verses, “Scotland Yard” is the oldest, first published in 1922. It might have an allusion to the great detective. Or maybe not.

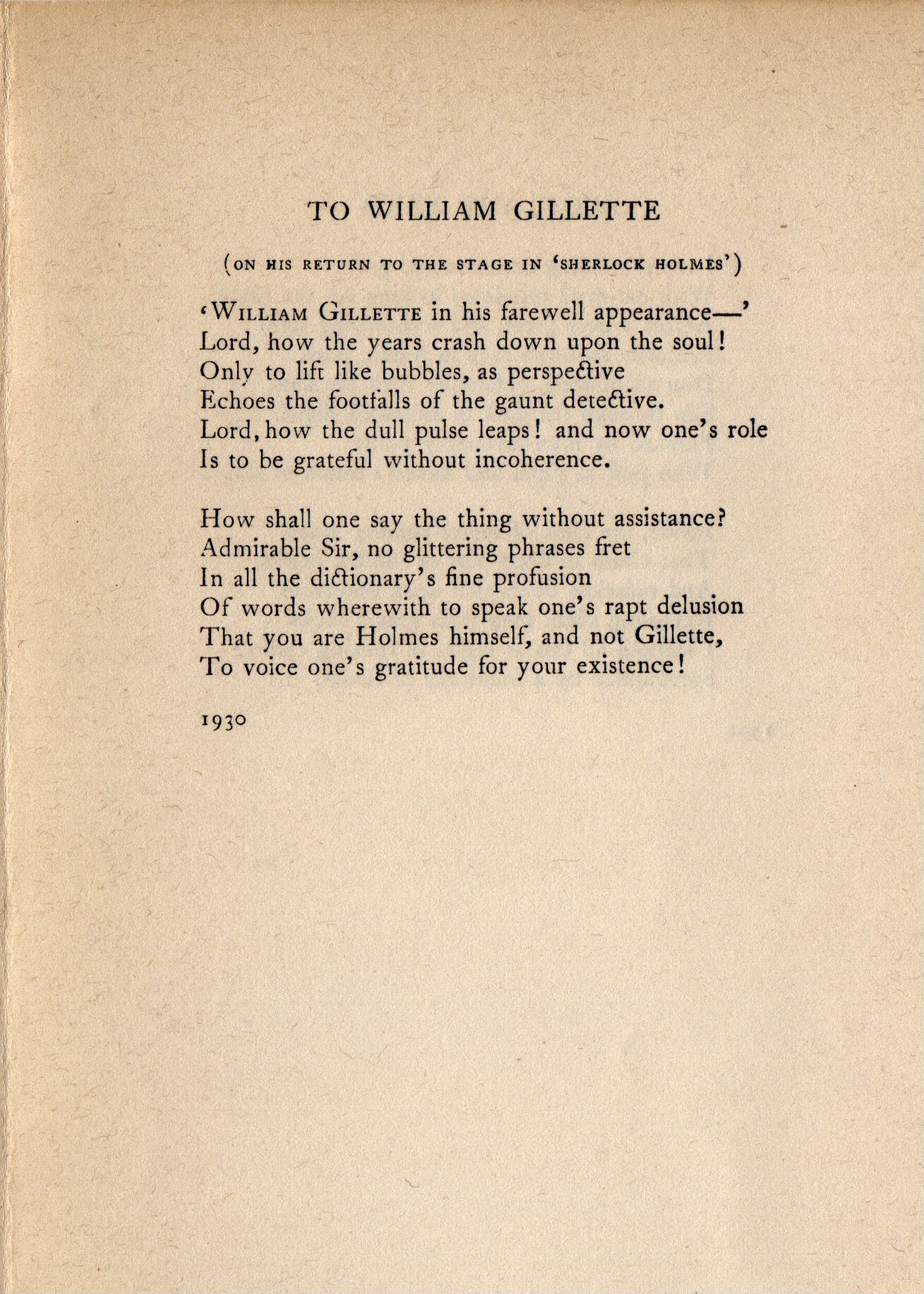

“To William Gillette: On his return to the stage in ‘Sherlock Holmes’ “ is more about the actor than the role, but the two had blended so well in the mind of the public (and in Starrett’s mind as well) that perhaps it doesn’t matter. Starrett wrote it in 1930.

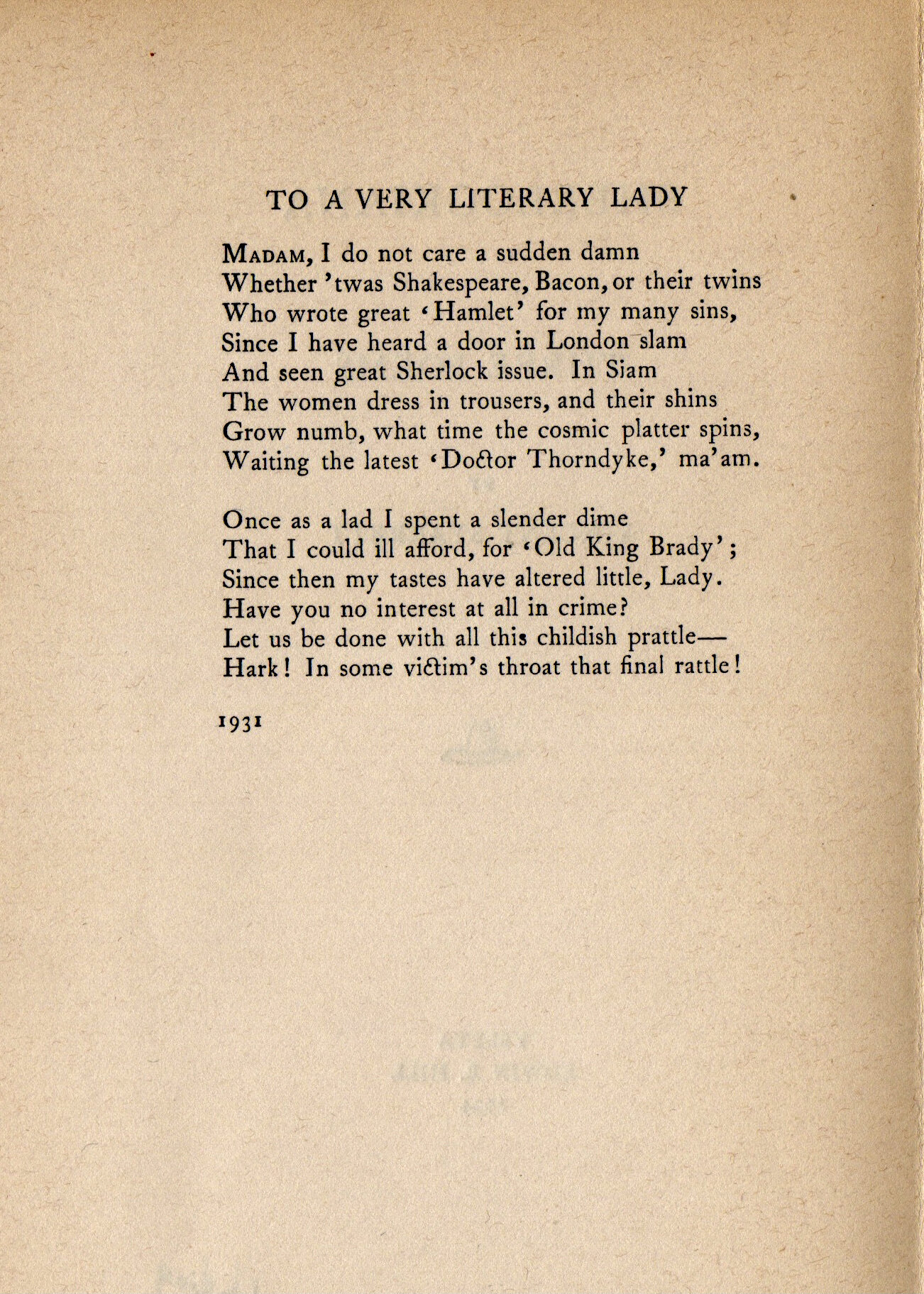

The next year brought one of his most popular verses, “To A Very Literary Lady,” which was first published in The New Yorker. Starrett lets a snobby matron know he prefers detective tales to more high-minded debates, like who wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

Once again, there were only 30 copies produced.

Sherlockiana: To an Undiscerning Critic by Arthur Conan Doyle. October 4, 1937.

There is a hiatus of three years in Sherlockiana before the next Holmes-based partnership between Hill and Starrett. Starrett had been out of the country for most of that time. The two had worked on a few other projects in the interim.

For his return, Starrett reprints a verse from the book Some Piquant People, written by Lincoln Springfield, and published in London in 1924 by T. Fisher Unwin. Springfield’s anecdotal history of Fleet Street was written after he retired from decades as a London newspaper reporter and editor, last at the Daily News.

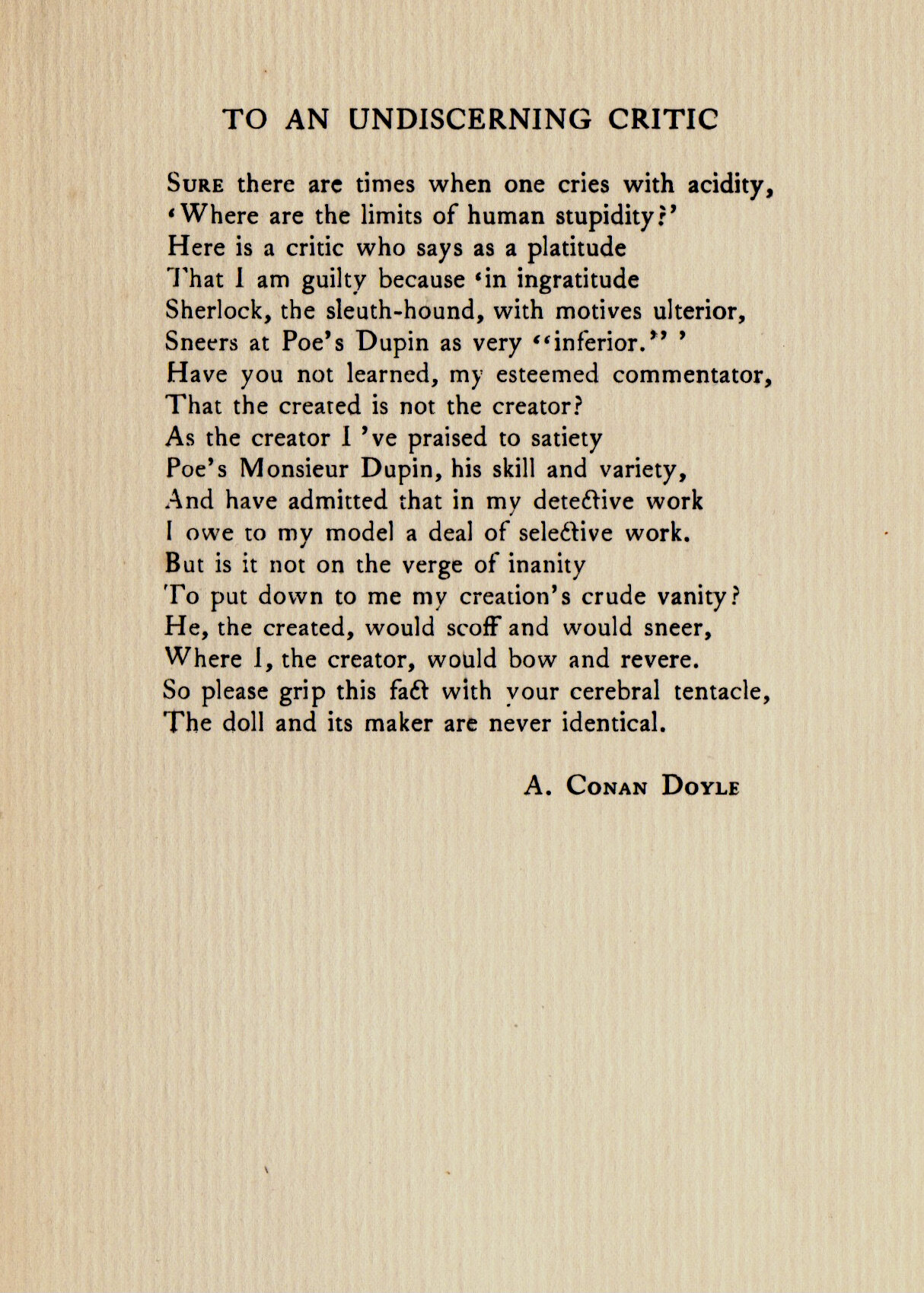

The book includes an interview with Dr. Joseph Bell, who discusses his relationship with Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes. It also has the first book publication of Conan Doyle’s poetical rebuke to a critic who chided the author for downgrading the work of Poe’s August Dupin.

This is getting a little long, so we’ll pick it from this point in the next post.