"The finest … of Holmesian scholarship"

Private Life bonus chapter: Haycraft has his say

“The finest flowering … of Holmesian scholarship occurred in the series of fond, wise and mellow essays by Vincent Starrett which were collected between covers under the irresistible title The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.”

—Howard Haycraft

I have been trying to figure out how to include this thoughtful and endearing essay on Private Life by Howard Haycraft for some time. In the end, I decided to put it here as a bonus chapter.

First, a little background.

By day, Haycraft worked for H.W. Wilson Company in New York, the firm that, among other things, published Twentieth Century Authors, British Authors of the Nineteenth Century and other standard references that were essential in the day before the interwebs came along.

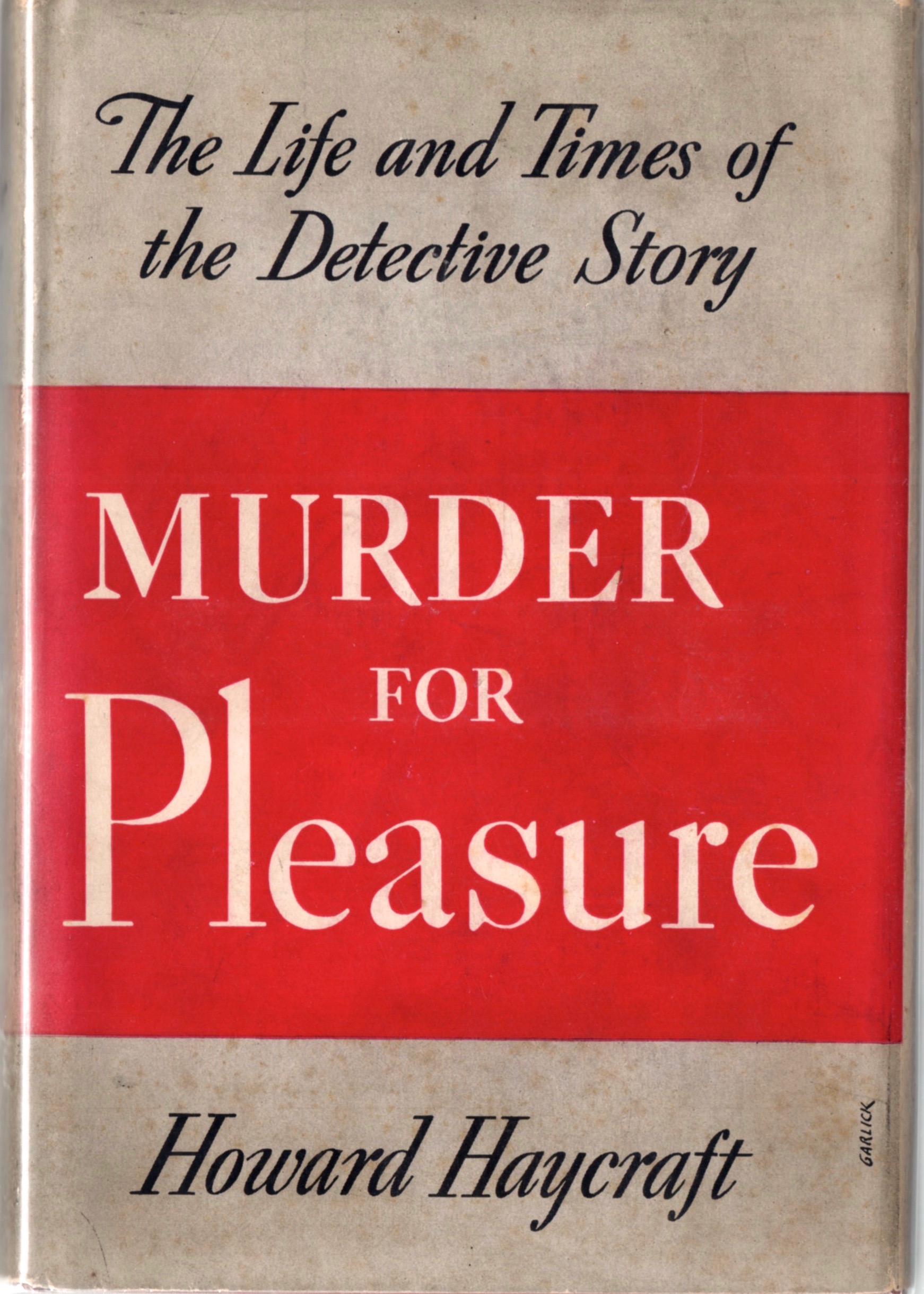

By night, he was a mystery and detective story fanatic, and in 1941 published a cornerstone work that is still worth reading: Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1943.)

Haycraft dove into the debate over whether mystery and detective fiction could also be good literature, and came out on the side of the hawkshaw. The book was popular in no small part, because those who had been secretly reading mysteries could now proudly bring them out of hiding.

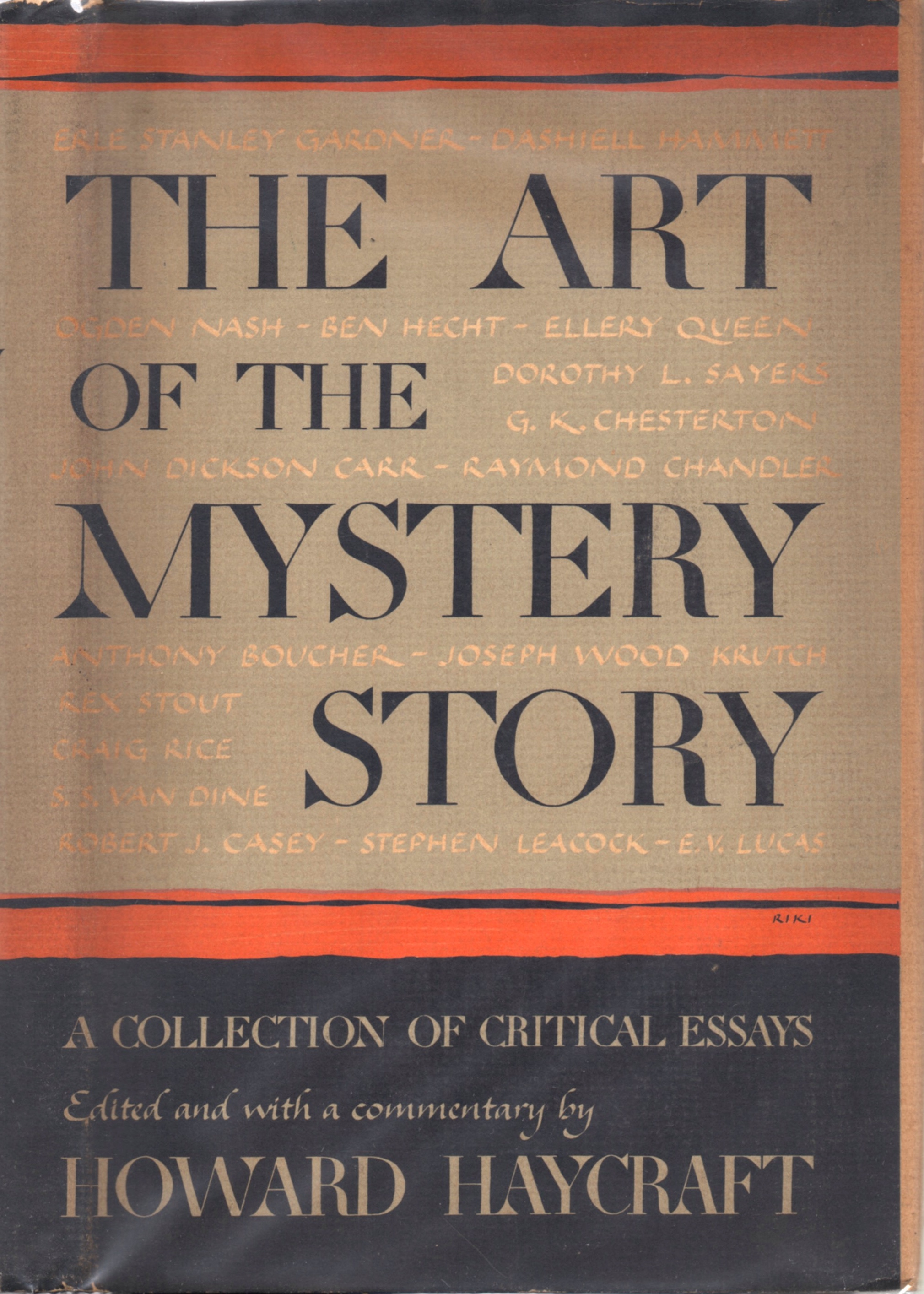

Haycraft’s next major work was The Art of the Mystery Story: A Collection of Critical Essays, published in 1946 by Simon and Schuster.

He cast a wide net, pulling in Edmund Wilson’s snooty, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?,” Dorothy L. Sayers’ thoughtful introduction to her The Omnibus of Crime (You should get this and read it. It’s good. Real good.), and S.S. Van Dine’s “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories.” (As for the latter, it’s fun to read a rule and then think of all the popular detective novels that violate the rule.)

Also included is Rex Stout’s audacious 1941 essay, “Watson was a Woman.” Haycraft playfully says Stout’s infamous essay created such rancor that Stout continued to attend BSI meetings “only when accompanied by a personal bodyguard.” (A Holmes fan himself, Haycraft was invested in 1950 as “The Devil’s Foot.”)

Also represented in the volume is Vincent Starrett, with the title essay to the 1933 book, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.”

It’s not Starrett’s essay I’m concerned with here, as enjoyable as it is. Rather, I want you to hear how Haycraft talks about Starrett’s book and his appreciation for the admiring way Starrett writes about Holmes. Haycraft starts by introducing the idea of “Holmesiana or Sherlockiana, or occasionally Watsoniana” as practiced by the Baker Street Irregulars and associated Sherlockians around the world. While tracing the history of the movement, he concludes: “The truth of the matter probably is that the game belongs to no single individual, but to the unique reality of Holmes himself.” He then turns his attention to Starrett’s masterpiece.

“With all respect to such other selfless toilers in the vineyard as Monsignor Ronald A. Know, H.W. Bell, S.C. Roberts, Mr. (Christopher) Morley and Edgar W. Smith, the finest flowering if not necessarily the earliest beginning of Holmesian scholarship occurred in the series of fond, wise, and mellow essays by Vincent Starrett which were collected between covers under the irresistible title The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, (New York: Macmillan, 1933; London: Nicholson, 1934). In your editor’s opinion they will never be equaled, much less surpassed, for sheer imaginative delight in their subject. Dealing explicitly with Holmes and Watson, they contain at the same time much that is implicit and valuable to know about the classical appeal of the detective story as a whole.”

If that wasn’t satisfying enough, Haycraft ends his introductory essay with this observation:

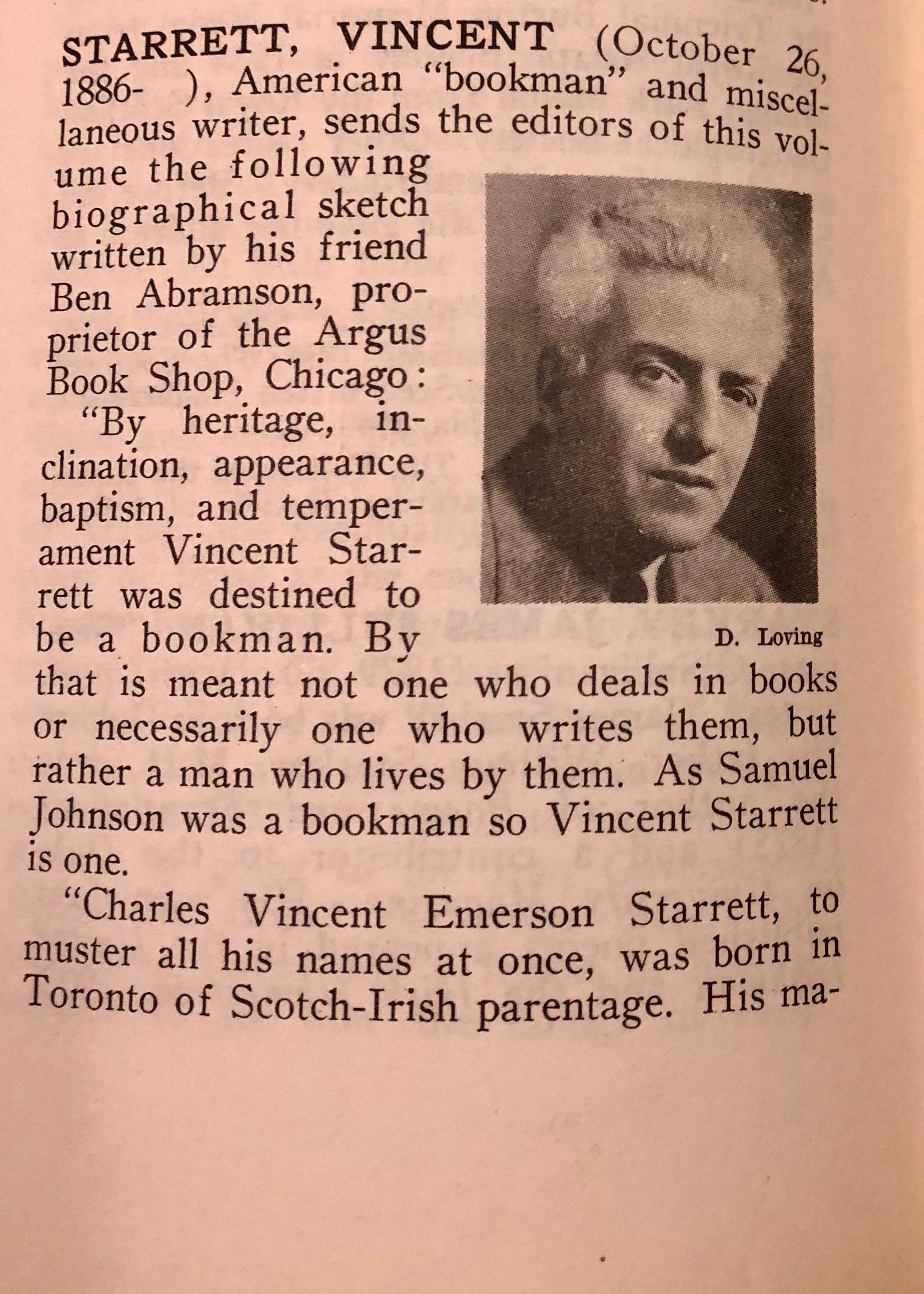

“Mr. Starrett is one of the few remaining American bookmen, in the true sense of that word. Like Doyle before him, his association with Holmes seems likely to overshadow his other numerous and substantial achievements, which include a number of enjoyable detective stories of his own and some beyond-the-average thoughtful criticism of police fiction in general. The selection chosen to represent him (and Holmesiology) in the present volume is the title essay from his book.”

Haycraft could not have been kinder to Starrett, and the old Chicago bookman must have burst with such praise. At the same time, Haycraft’s prediction about Starrett’s own detective mysteries fading behind his Holmes-work was all too prescient. Late in life, Starrett was grateful for his popularity among Sherlockians, but saddened that his considerable library of work had been forgotten.

The fat, green spine of Twentieth Century Authors. A familiar sights to those of us who haunted libraries in the 60s and 70s and used volumes like this to get information about writers for high school and college essays.

Haycraft left behind one additional essential item for those interest in detective stories.

In Life and Times of the Detective Story, Haycraft published a list of cornerstone works. Ellery Queen expanded on the list and updated it over time. The Haycraft/Queen list of cornerstone works was, for many mystery/detective collectors, an essential guide to the genre. Book dealers continue to cite it in their listings.

When Haycraft died at 86 in 1991, The New York Times asked Otto Penzler about Haycraft’s first and most famous book, Murder for Pleasure.

"At the time of its publication it was the most important single work of fiction-mystery scholarship ever produced," Otto Penzler, the owner of the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, said yesterday.

"It remains the most insightful, perceptive and fair-minded book ever written on the subject."

IMHO, if you combine Murder for Pleasure with The Art of Murder, Otto’s assessment holds true today.

“The truth of the matter probably is that the game belongs to no single individual, but to the unique reality of Holmes himself.”

—Howard Haycraft