Mr. Starrett Collects Mr. Crane

One of Starrett's first passions: Stephen Crane

The first page of Starrett's lengthly article about Crane from The Colophon, A Book Collector's Quarterly, Part Seven, 1931.

"Collecting Stephen Crane is a labor of love. Few of the purely speculative collectors have got around to him as yet. With a few exceptions, it is possible without difficulty to obtain his books in first editions. Certain it is, though, that more and more as the years pass will his works increase in fame, and consequently (in their initial appearances) in value; wherefore, it behooves the really earnest admirer whose purse is lean to speed himself."

Starrett could have been talking about himself in that quote from page 6 of A Bibliography of the Works of Stephen Crane, a little work "compiled and with an introduction by Vincent Starrett" and published by The Centaur Book Shop in Philadelphia in 1923.

Starrett's purse was lean enough, but he was dogged. Published during one of Starrett's most prolific periods, the little booklet was, as he notes, a labor of love, and many of his entries were from his own significant Crane collection.

Starrett was not a classically trained scholar. In fact, he left high school before graduating and never went to college. So his efforts at putting together bibliographies have sometimes been looked down upon by others. I am not expert enough to pass judgment.

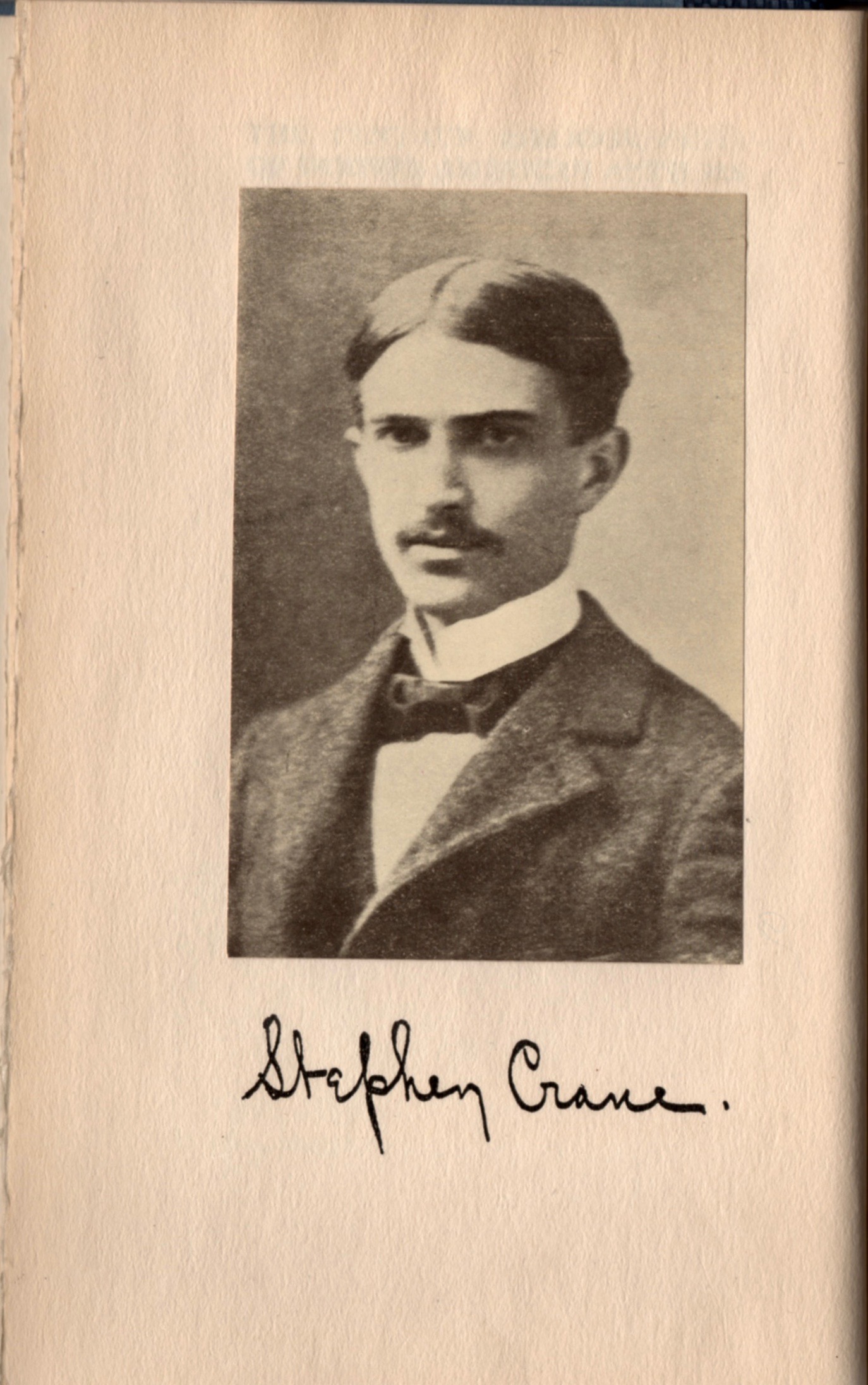

The fact is that when it comes to Crane, Starrett was there in the first wave and Starrett's work had an influence on many others for decades to come.

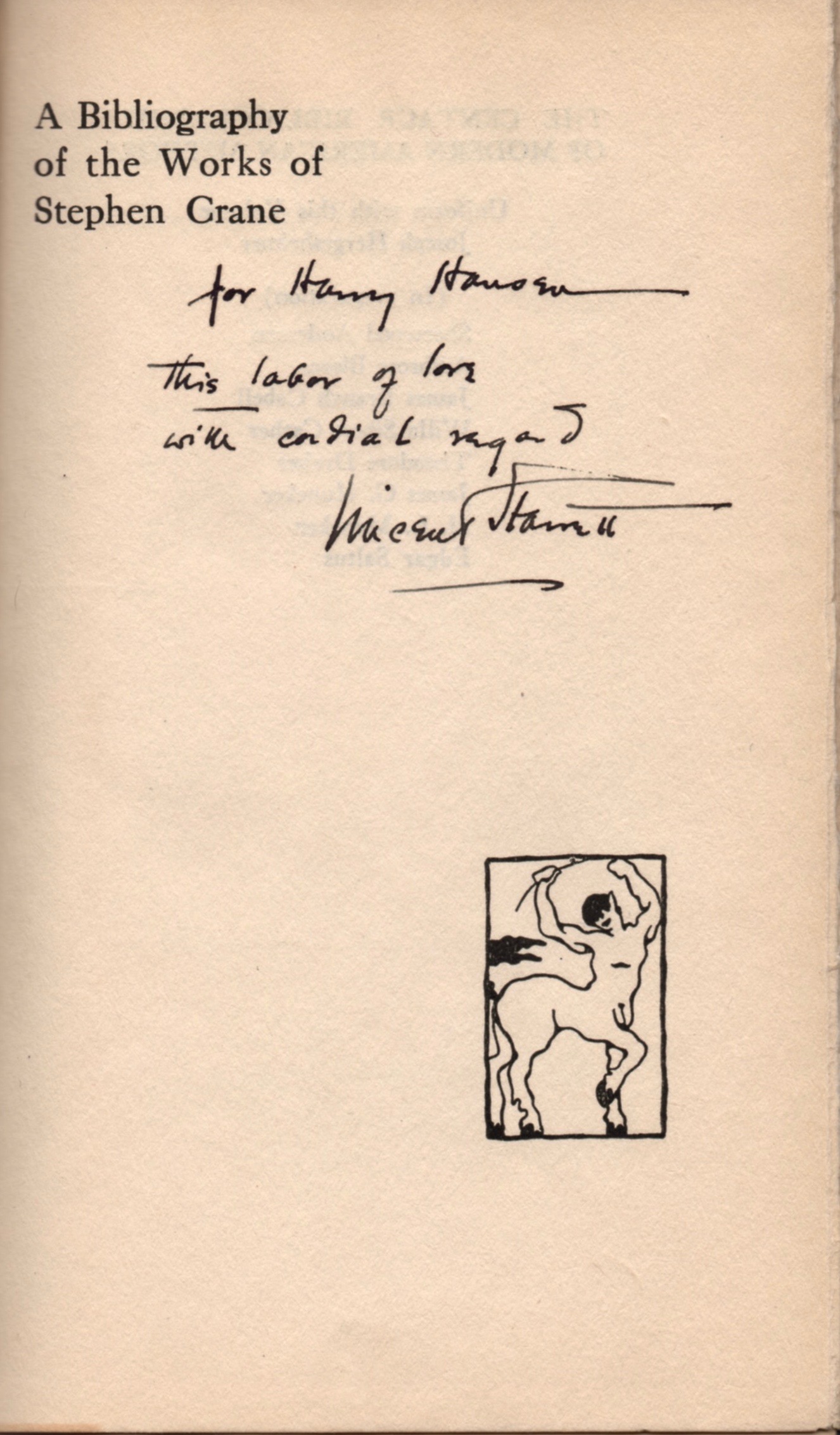

I have a rather good copy of A Bibliography of the Works of Stephen Crane, and it has a very nice association. It is dedicated to Harry Hansen, who was a colleague and sometimes editor of Starrett's back in the early years of Starrett's Chicago newspaper career. The inscription reads:

"For Harry Hansen, This labor of love, with cordial regards, Vincent Starrett."

The impact of Starrett's efforts to publicize the works of Crane seems to have been enormous.

As John T. Winterich said while reviewing an updated version of the bibliography for the Saturday Review of Literature in October 1948:

"Vincent Starrett blew a lusty trumpet in the Crane-renaissance parade a quarter century ago, and he has been tooting and marching ever since. His call, indeed, has grown more clarion, his stride sturdier. His Crane bibliography of 1923 was an affair of forty-eight pages, but it was a mighty useful tool to the Crane student at the moment, and has been ever since."

Winterich goes on to heap equal praise on the new bibliography by Ames and Williams. (See below.)

"(B)oth Mr. Williams and Mr. Starrett know their Crane; both know his books; both understand the niceties of description and collation."

That is certainly a friendly pat on the back by a man who was a bibliophile in his own right.

The title page from Men, Women and Boats.

When The Modern Library needed someone to edit a book of Crane short stories, they called on Starrett. He titled the collection Men, Women and Boats. It was a selection of mostly published works, although some were not easily available in the United States. There were also a few stories published here for the first time.

As is true of all Modern Library editions, there were multiple printings. I own copies with brown and green covers. Both say the contents were copyrighted 1921 (two years before Starrett's bibliography), but I don't know enough about Modern Library editions to tell you which came first. They're both showing their age and are pretty tender.

I doubt anyone but Crane scholars will recognize the tales collected here. Of all the stories, I was most struck by "A Dark Brown Dog." A child finds a small dog with a rope around its neck. The child plays with the dog and then cruelly leaves him, but the dog follows the boy home, where both child and dog are abused. The ending is particularly heartbreaking. Like many Crane stories, its clarity and insight lend it to being taught in school, as you can see here.

(By the way, Starrett also did the introduction to a Modern Library edition of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and Other Stories. I don't own a copy of that book. Yet.)

(Another parenthetical thought: Starrett most likely owned first editions of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and The Red Badge of Courage. They would be fun—but expensive—to hunt down. And I wonder, are Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and The Red Badge of Courage taught in literature classes these days?)

The shelves hold a few more Crane/Starrett items.

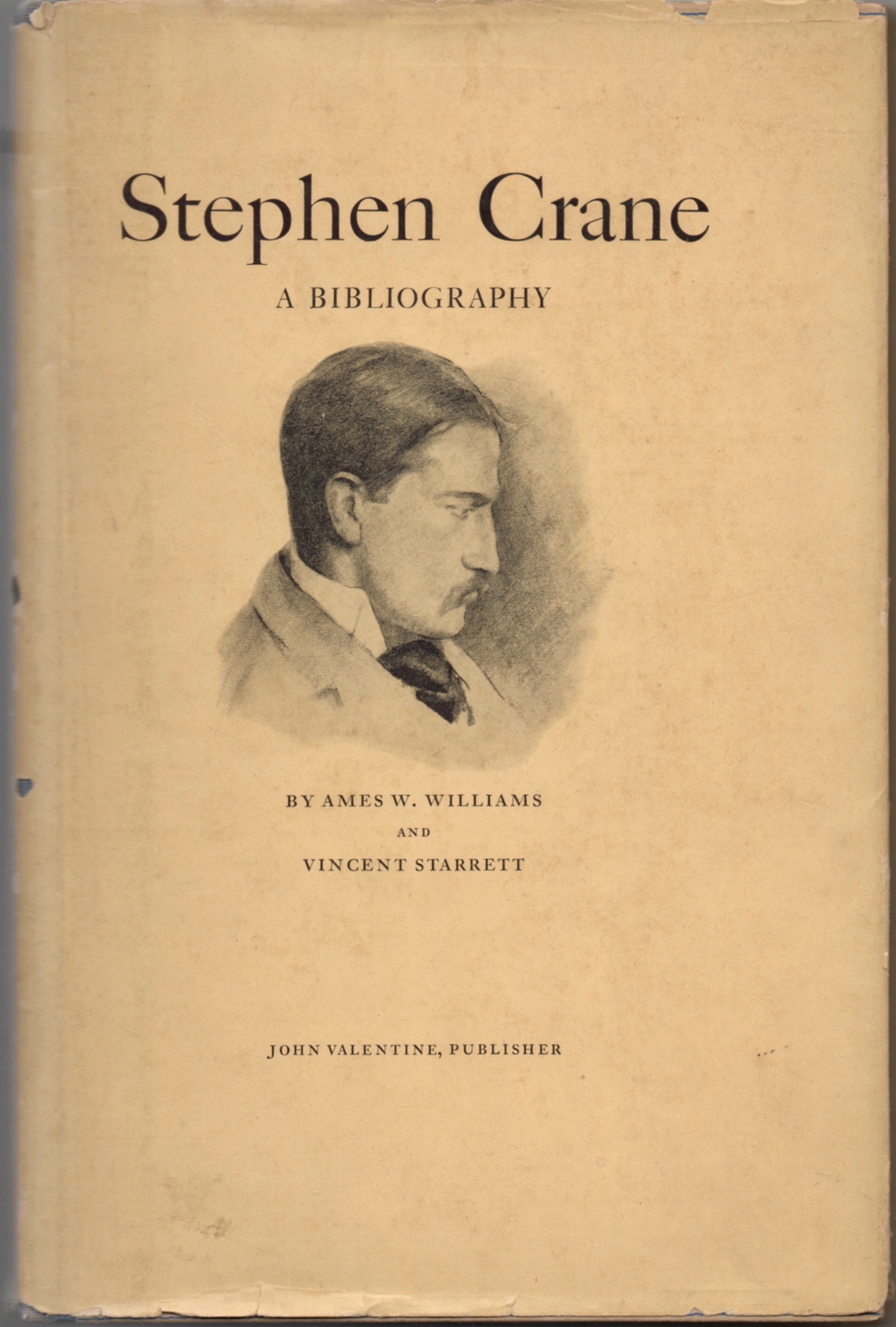

First is the 1948 revised bibliography that John Winterich spoke of earlier, Stephen Crane: A Bibliography, published by John Valentine of Glendale, California. Starrett rarely collaborated with others, so this is a bit of a rarity. Ames W. Williams, however, was every bit a Crane collector as Starrett, so their sympathies certainly provided a basis for collaboration.

Unlike Starrett, Williams was a college graduate, having a bachelor's and law degree from George Washington University. He held several posts during his career, ending as an administrative law judge.

At his death in 1991, Williams donated his collection of Crane materials to Syracuse University, where Crane studied.

Remember that school, Syracuse. We'll come back to it at the end.

The introduction to this volume is an updated and expanded version of the one Starrett wrote for his solo bibliography. I suspect Williams updated the bibliographical material that makes up the bulk of the book. (Starrett had likely sold most of his Crane collection by this point.) That might also explain why Williams' name appears first on the book.

The book was reprinted in 1970 by Burt Franklin of New York in an edition intended for library use. So the foundation that Starrett had laid down with his bibliography in 1923 was still actively being used in its updated form nearly 50 years later.

Not bad for a self-taught bibliographer.

I have one other item which relates to Starrett, Williams and Crane.

In April of 1942, Starrett's old friend Edwin B. Hill published a brief, well, I don't know exactly what to call it. It was certainly written by Crane, but I can't make heads or tails of it myself. Probably a poem, but it's free form to be sure. Starrett himself merely calls them "these lines."

Here's what Starrett had to say about it:

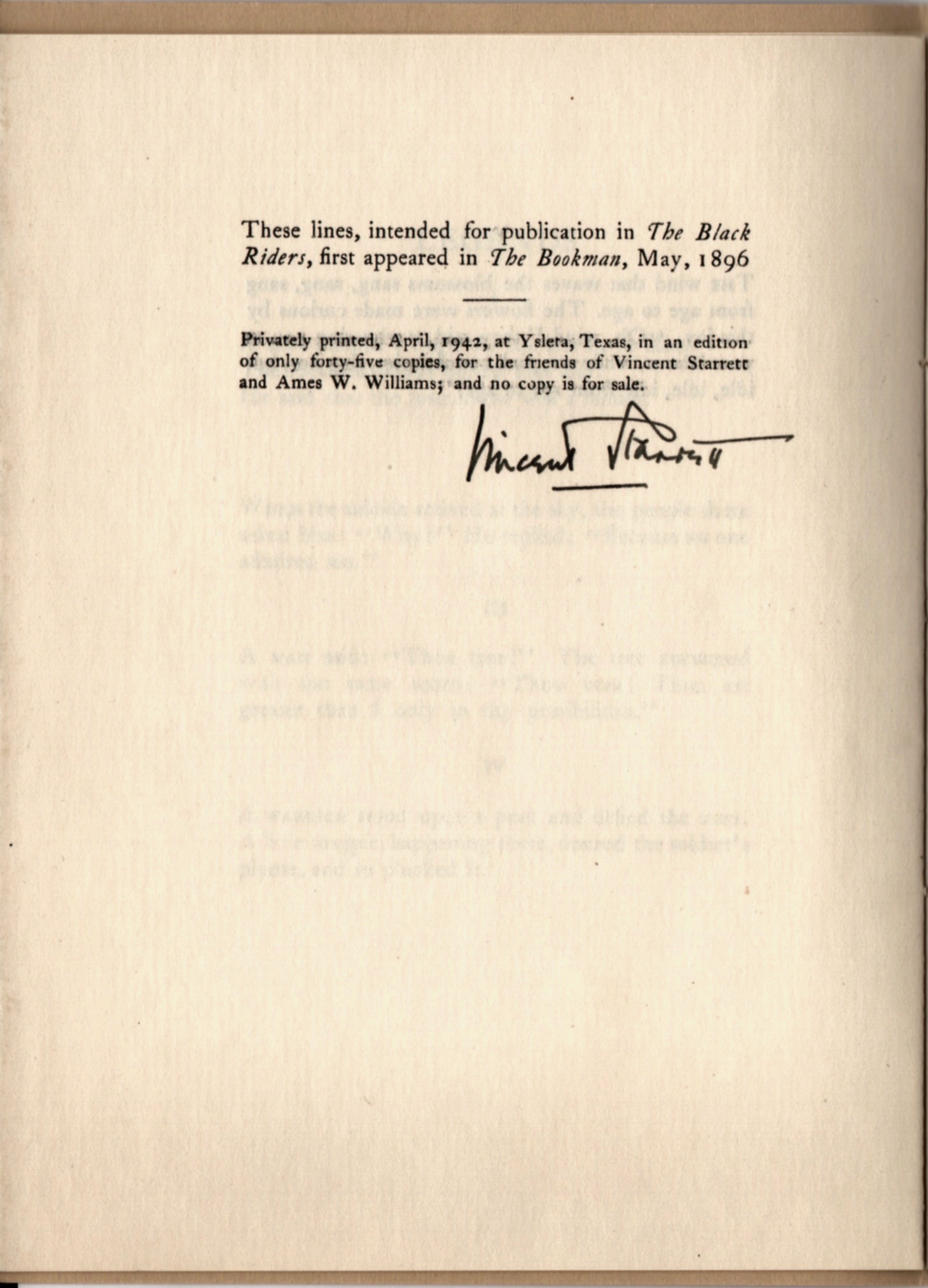

"These lines, intended for publication in The Black Riders, first appeared in The Bookman, May 1896."

The booklet was published in an edition of "only forty-five copies, for the friends of Vincent Starrett and Ames W. Williams; and no copy is for sale."

This work originally appeared in The Bookman, whose pages assiduously charted the popularity of the Baker Street detective. The Black Riders is a book of Crane's poetry published in the mystical year of 1895. If you look at the Wikipedia entry, you'll see where Edwin Hill got the cover illustration for this little booklet.

Why republish this obscure work? Perhaps the lines in this booklet spoke to Starrett and Williams as war raged in Europe. I can't be sure. You can decide for yourself.

A Late Entry

A few weeks after I had finished this post, I was able to purchase a letter that, at first, seemed to be relevant to this topic, but was puzzling. The letter was to a John S. Wayfield and mentioned the Stephen Crane Legends piece.

I posted the image to the Studies in Starrett FaceBook page. Sharp-eyed reader Steven Rothman (He is, after all, the eagle-eyed editor of the Baker Street Journal) said it was not Wayfield but Mayfield. Suddenly it all made sense.

John Mayfield was a Crane collector in his own right. A curator of rare books and manuscripts at Syracuse University from 1961 to 1971, Mayfield put together a nice collection of books about the university's famous author for himself, and later for the university.

And remember the Syracuse reference from above? Williams sent his Crane collection to Syracuse after his death. Mayfield was gone by the time this happened in 1991, but it's nice to see the circle completed.

This letter from 1946 is clearly one is a series between Starrett and Mayfield. While we don't have the previous piece of correspondence, this letter makes it clear that Mayfield was trying to get in touch with Ames Williams. At this point, Williams and Starrett were working on their joint bibliography which was published in 1948. Perhaps Starrett helped the Mayfield and Williams get in touch. Says Starrett:

"I'm glad you and Ames Williams have connected at last."

And it's also clear that Mayfield wanted Starrett to autograph a copy of the little 1942 Legends brochure discussed above. Mayfield must have gotten one of the rare 45 copies.

"Yes, indeed, send me the Crane: LEGENDS and I'll be happy to sign it."

And that, dear friends, is where we will be happy to end.