Sincerely, Tony/Faithfully, Vincent

Boucher and Starrett: Brothers in Sherlock

Anthony Boucher's Sherlockian works, as compiled by Jeffrey Marks for his book Anthony Boucher: a Biobibliography, published in 2008 by McFarland & Company, Inc. of Jefferson, North Carolina.

Have the Baker Street Irregulars paid tribute to Anthony Boucher during the salute to “An Old Irregular” at the annual dinner?

If not, he should shoot to the top of the list for a future gathering.

I say this because lately I’ve been pondering the relationship between Boucher and Starrett, and came away pleasantly surprised at Boucher’s impact on the Sherlockian world.

As an example, just take a look at that page of Sherlockian writings from Jeffrey Marks’ book Anthony Boucher: a Biobibliography, published in 2008 by McFarland & Company, Inc. of Jefferson, North Carolina. (If you have any interest in Boucher, Marks' book is very readable. )

The list is impressive and doesn’t even include The Case of the Baker Street Irregulars, which we will consider a little later in this essay. (Marks includes the novel elsewhere in his book.)

Why did this come up now?

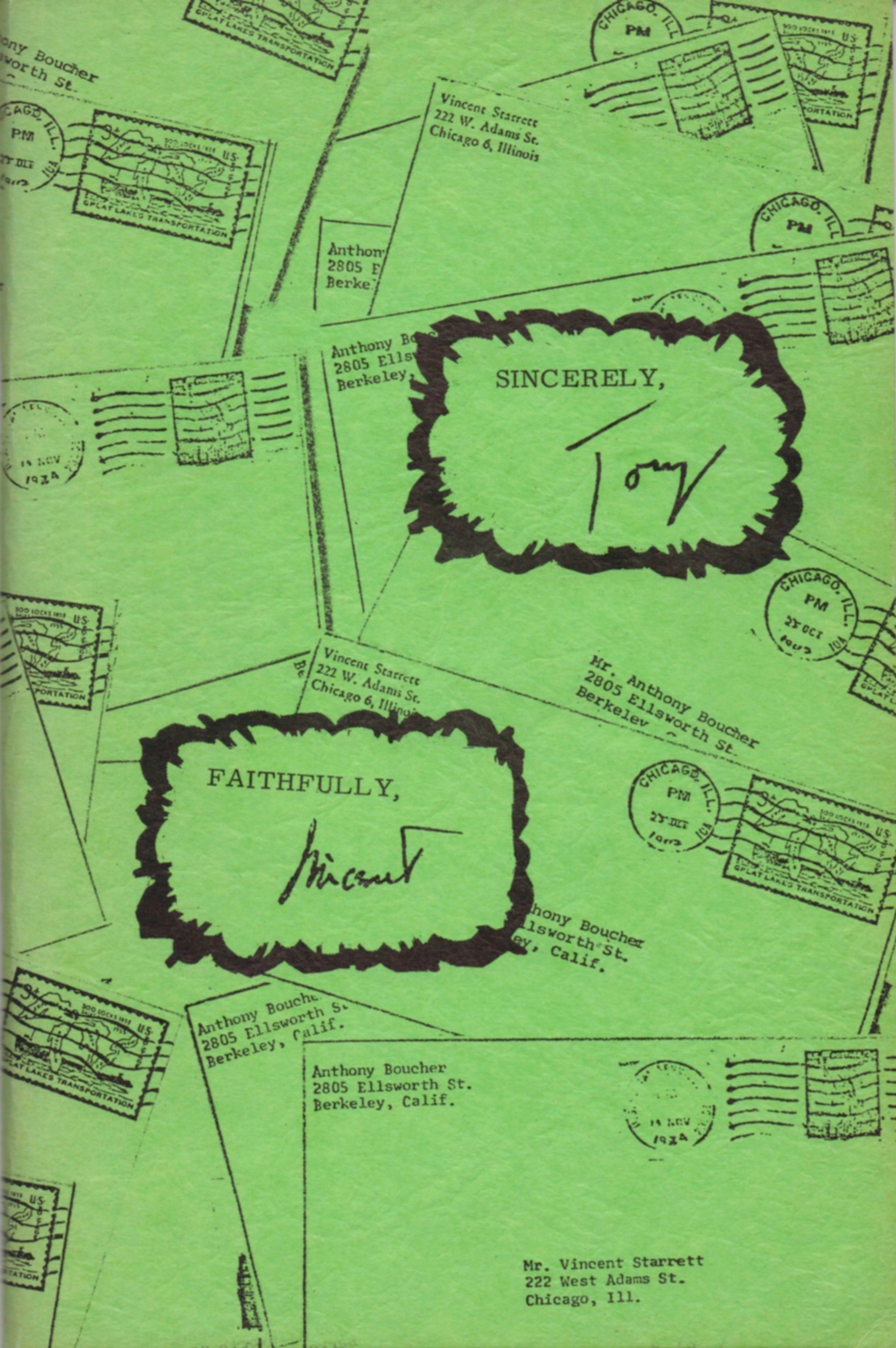

Naturally, it all started by accident. I was pulling out an adjacent work on the shelf when a slim booklet with bright green coversalmost plopped on the floor.

From such incidents are blog posts inspired.

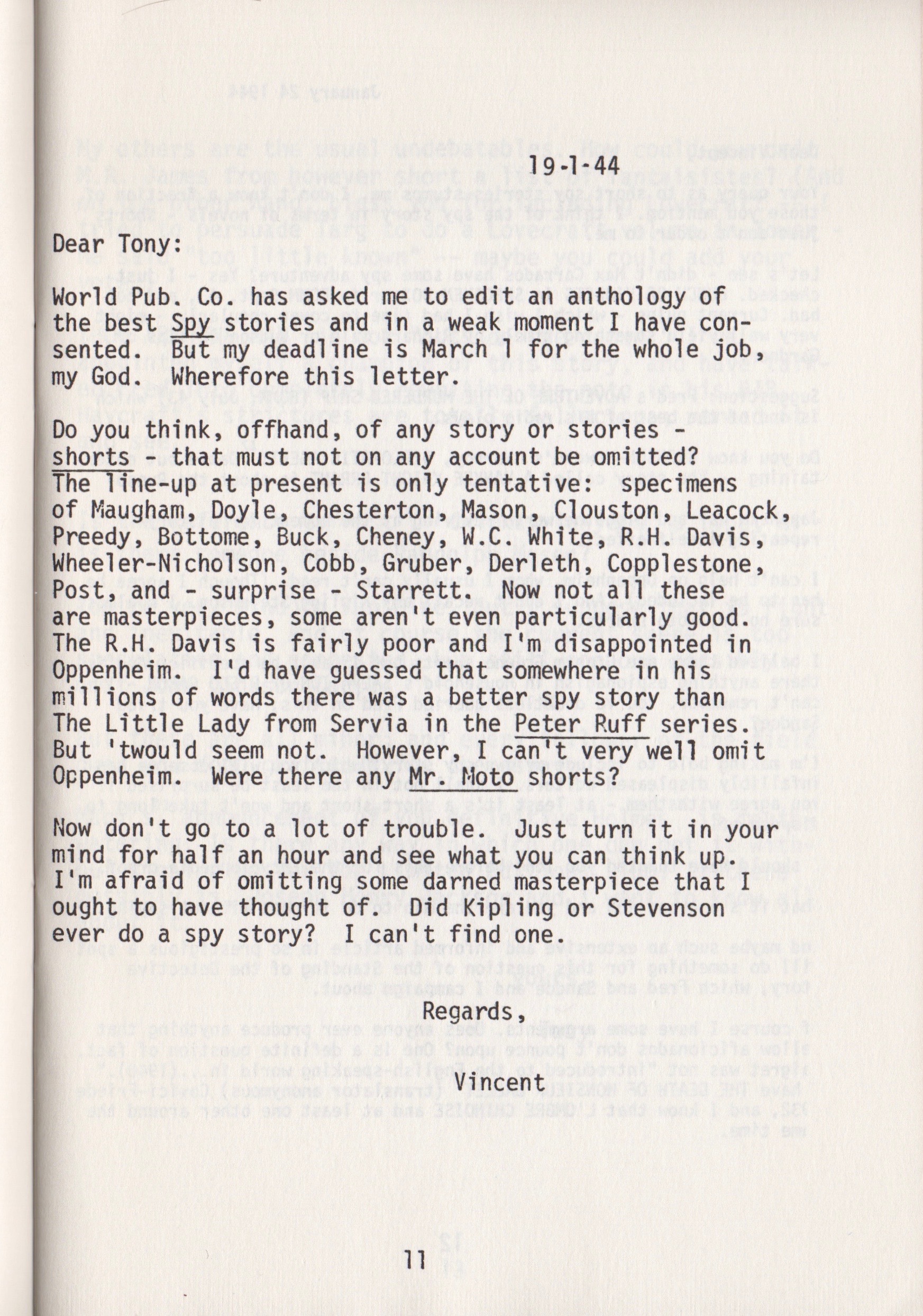

Back in 1975, the late Irregular Robert W. Hahn published a booklet that gives a glimpse into the relationship between the two writers and editors from the last century. Sincerely, Tony/Faithfully, Vincent: The Correspondence of Anthony Boucher and Vincent Starrett is by no means the complete correspondence between these two men, but it does offer a look into their lives in the 1940s and 50s as their interests crossed and reinforced one another.

In his brief introduction, Hahn (who was an Irregular, and a member of the Hounds of the Baskerville (sic) and Hugo’s Companions), notes that while reading other people’s mail is generally frowned upon, reading the correspondence of two gifted writers can help fill out our pictures of their plans and progress.

“In the literary field, there is no more gratifying experience than the perusal of those volumes of collected correspondence in which authors exchange ideas on life and their art, and give free vent to their feelings of joy, or sorrow, or frustration. It is rewarding, indeed to come across a passage in a letter form some famed author that gives form and clarity and style to an emotion or to a thought experienced or held by the reader.”

When the book was published in 1975, both Starrett and Boucher were both just recently passed beyond our ken. Boucher had gone first, in the spring of 1969, and Starrett followed in 1974. At just 56 pages (including extensive footnotes), the booklet is worth a few moments consideration.

But first let us briefly comment on Anthony Boucher.

Those of you who have attended Bouchercons over the years no doubt have a good idea of how the fan-driven symposium of mystery aficionados got it’s name.

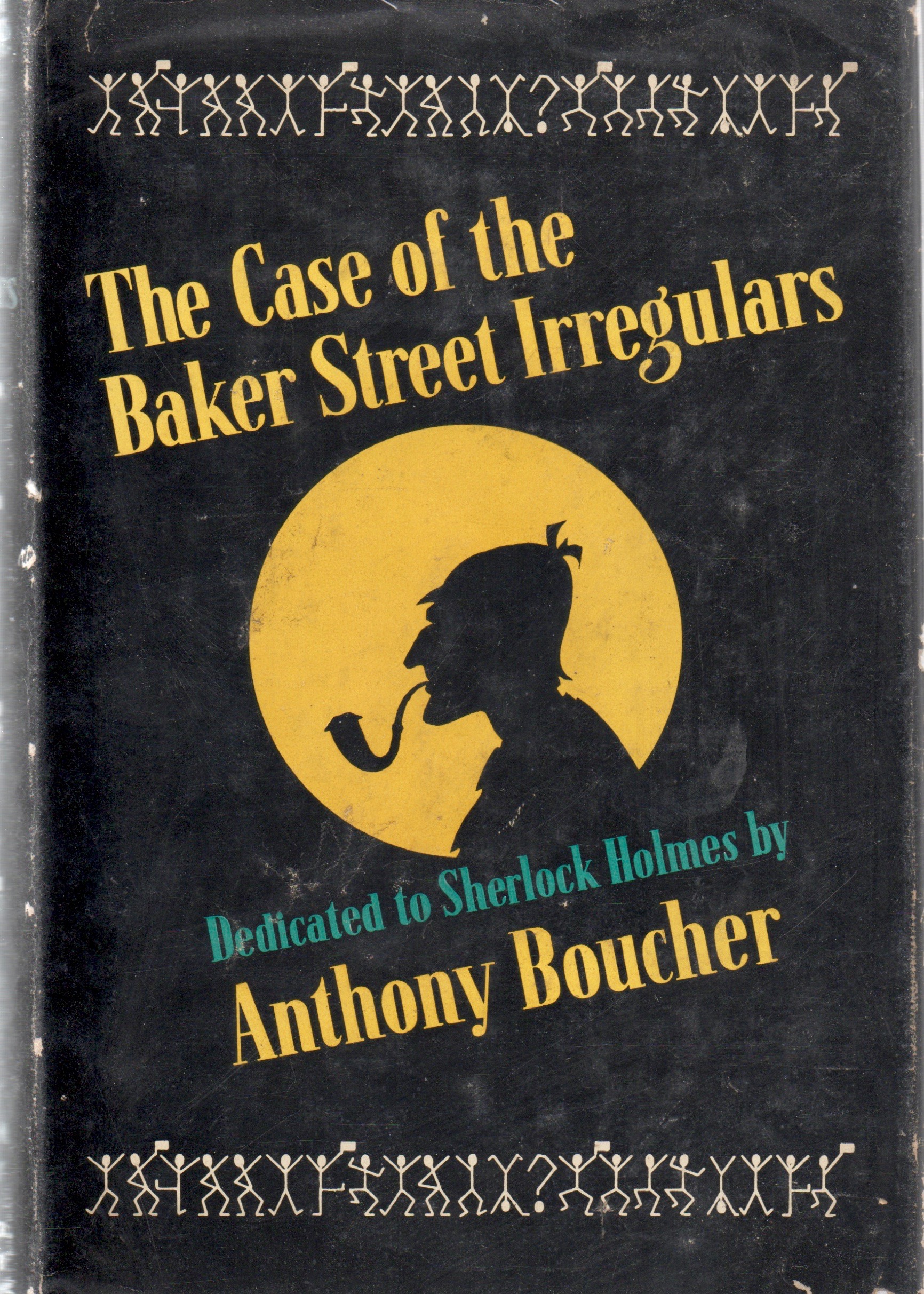

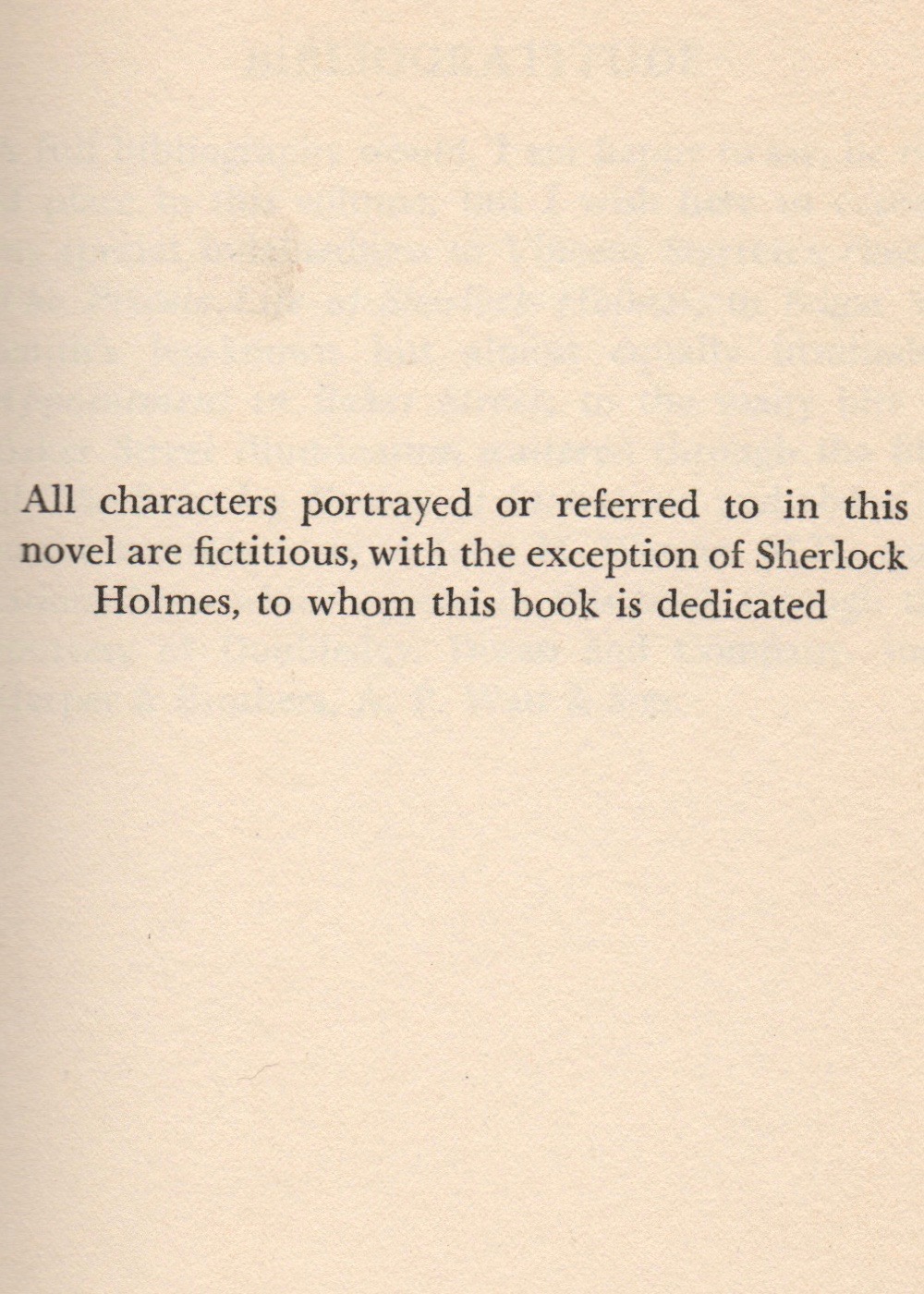

I met Boucher, or rather his work, in another way. While hunting through the library at West Virginia University as an undergraduate, I ran across Boucher’s 1940 tour de force murder mystery novel, The Case of the Baker Street Irregulars, published by Simon & Schuster.

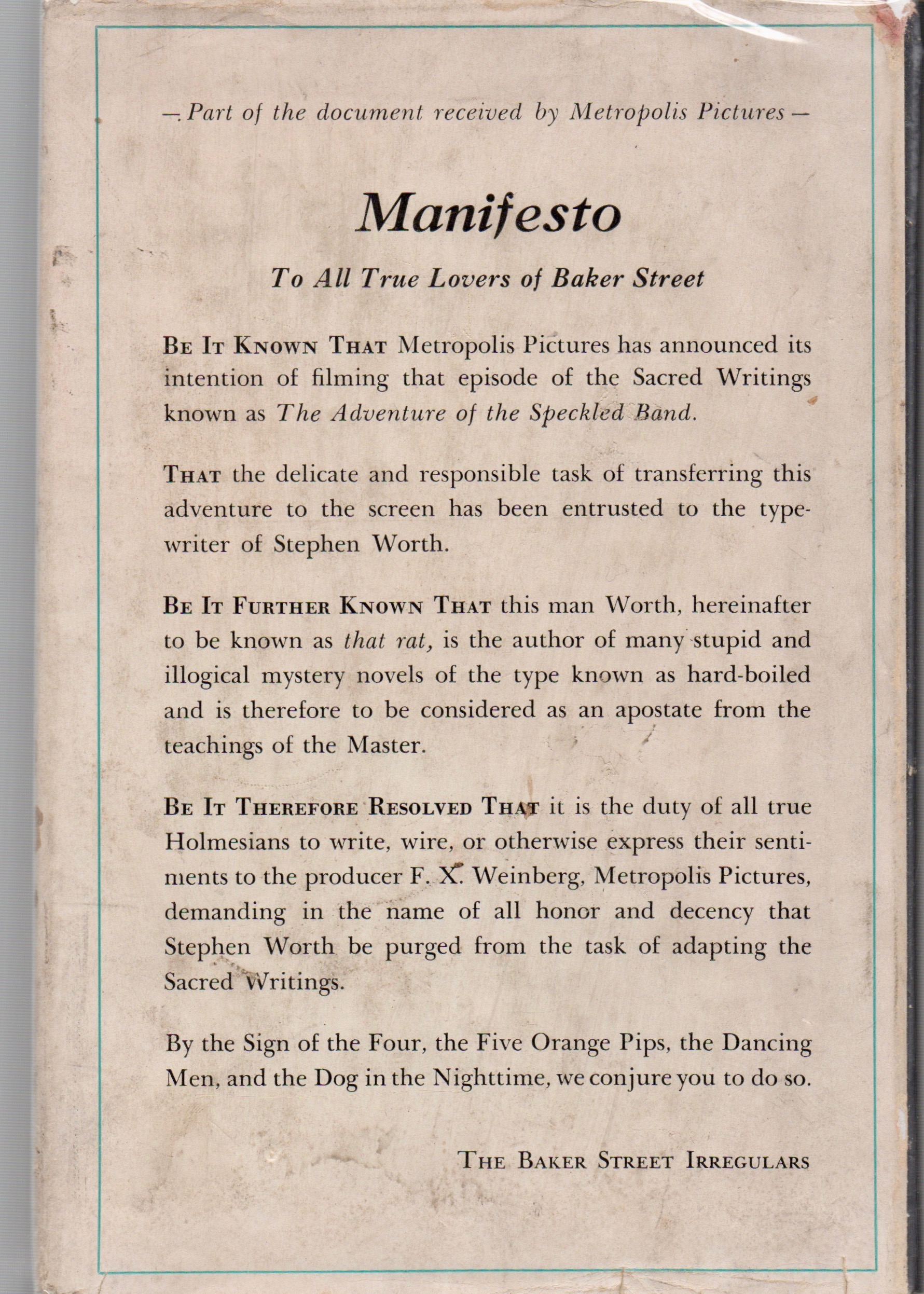

Think about that for a minute: The BSI was founded just six years earlier, and yet here is a mystery story built around the organization, that includes its recently minted Constitution and Buy-Laws in the first chapter. Not only that, but the novel riffs on the BSI’s “colorful” obsession with Holmes and fealty to The Canon. In 1940, the BSI was still in its infancy, still fragile enough that one person’s decision could threaten to end the Irregulars.

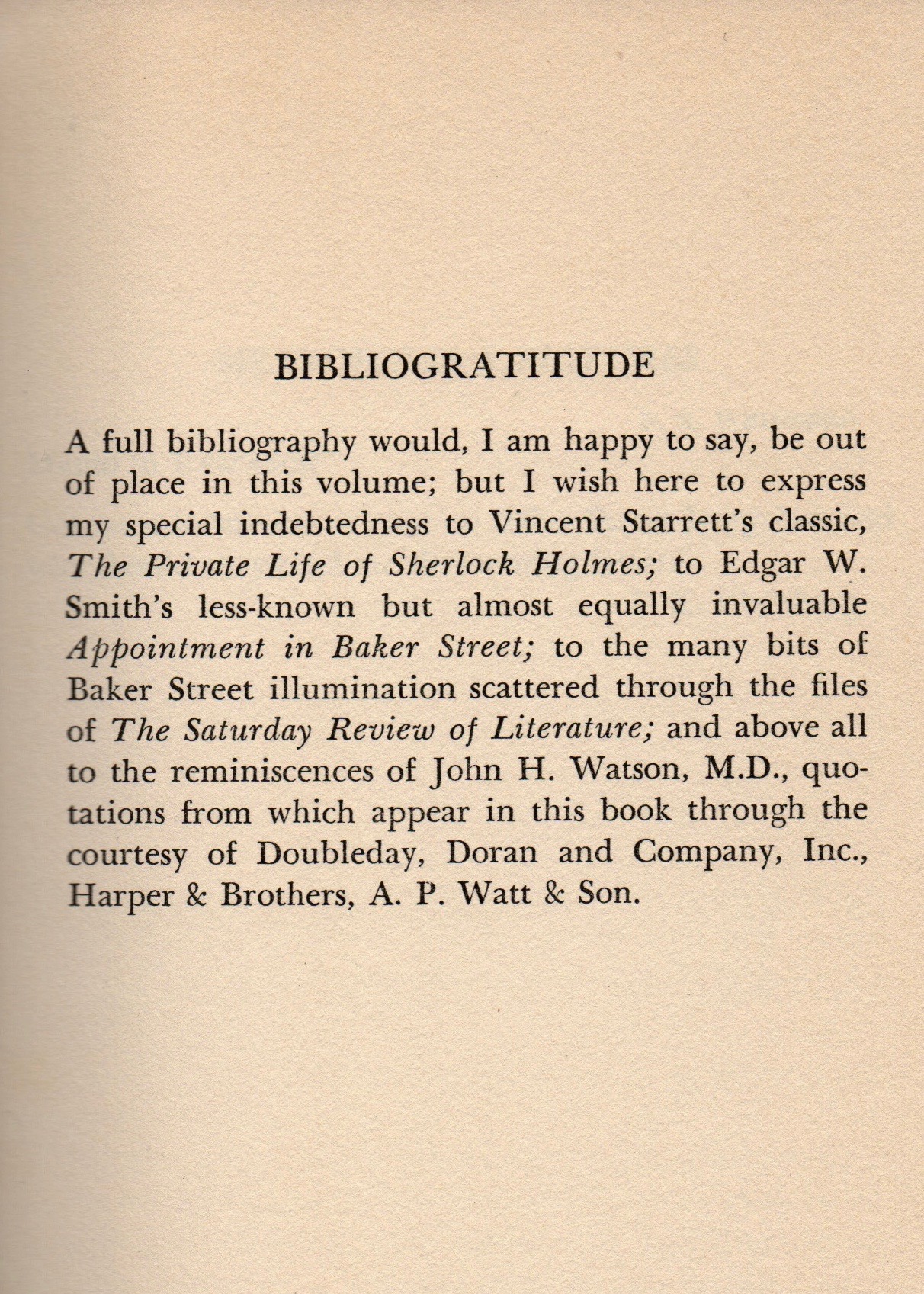

And yet, here was this guy, who was not an Irregular, but a talented mystery writer living in California who had somehow cracked the BSI code. Boucher might have been an outsider, but he had tracked the progression of the world of Sherlock Holmes, starting with Starrett’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes and following the conception and actions of the BSI through Christopher Morley’s Bowling Green column in Saturday Review of Literature. (See his note of "Bibliogratitude" in the carousel of images in this section.)

Edgar Smith was so stunned by this book that he first thought that Boucher was actually an alias for one of the known Irregulars. He simply could not believe that an outsider could produce something like The Case of the Baker Street Irregulars.

It turns out that what Smith, Morley and Starrett saw in The Case of the Baker Street Irregulars was one of Boucher’s superpowers: An ability to sense how popular culture was intertwining with books and characters outside of books and then translate that into new forms of entertainment.

And in this, Boucher and Starrett were brothers.

An aside:

The Case of the Baker Street Irregulars was not Boucher's only foray into blending murder among genre devotes.

Boucher did something of the same for nascent science fiction fandom when he published Rocket to the Morgue, a murder mystery with science fiction writers instead of BSI in the mix.

Here’s my 1951 paperback copy published by Dell. It's been a part of my collection for more years than I can remember.

The book was first published in the 1940s under an alias, H. H. Holmes. Fans of serial murders will remember that was the name of the killer who operated in Chicago during the 1893 World's Fair.

Back to Sincerely, Tony/Faithfully, Vincent.

The letters we have at hand in Hahn’s book are a scattered correspondence, but show a few clear traits.

The relationship between the two became familiar enough to call each other by their first names. (What starts as “Dear Mr. Starrett” and “Dear Boucher” soon becomes “Dear Vincent” and “Dear Tony.”)

Both men sought out the other’s advice on their projects, trying to tap into the others knowledge of spy, mystery and detective tales.

They became so close that when Boucher started attending BSI dinners in the early 40s, he would make it a point to stop over in Chicago between train trips to have lunch with Starrett. These events would come to mean as much to him as the dinners themselves.

What is obvious from the limited letters published here is that these two men respected each other and became brothers in Holmes and genre fiction.

I have already written more than I intended, but said less than I ought. Perhaps I’ll return to the topic at another time.

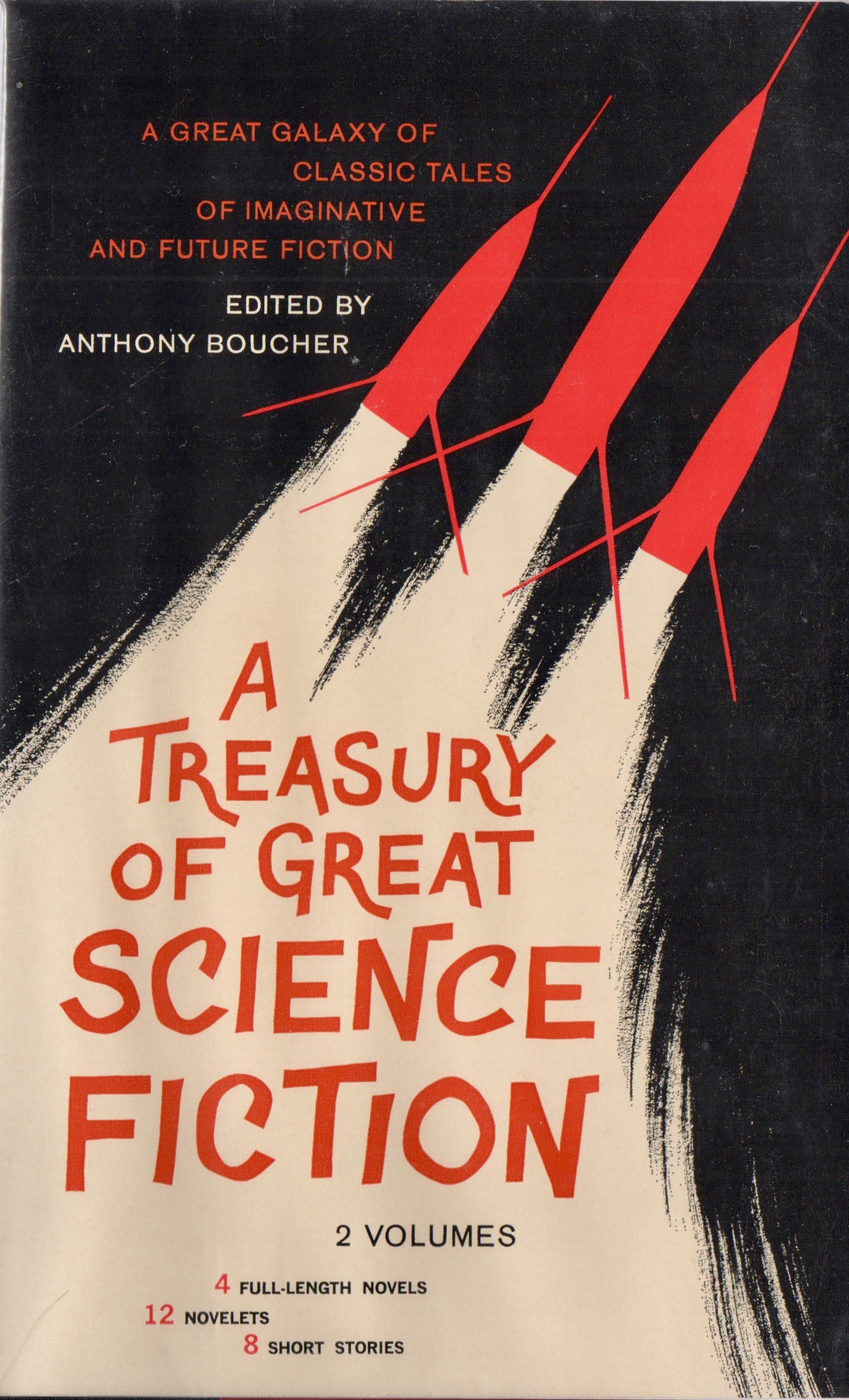

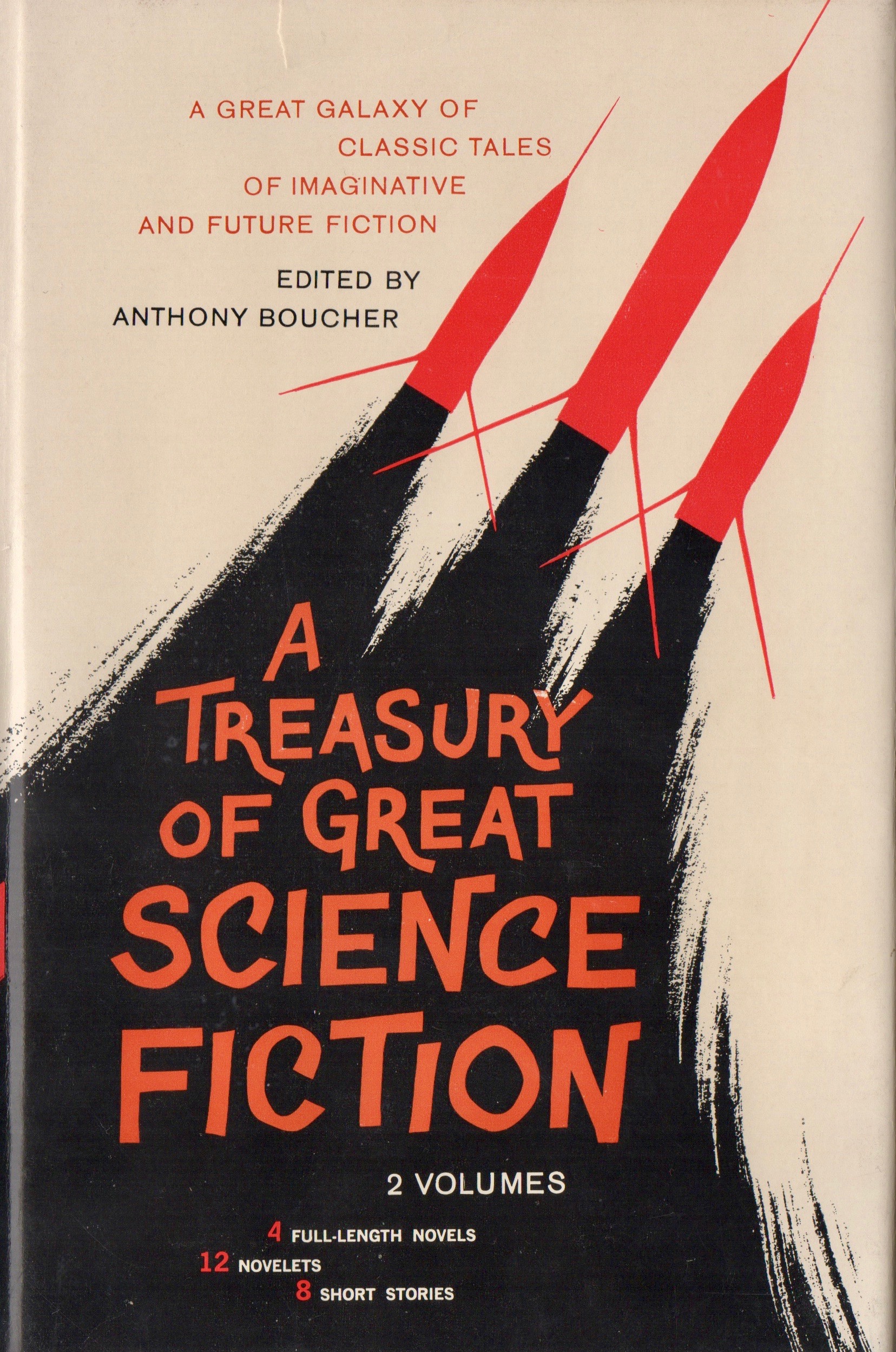

Until then, here’s another favorite pair of volumes from Boucher’s literary output, A Treasury of Great Science Fiction, published in 1959 by Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Like Rocket to the Morgue, I have been hauling these around for decades, and still dip into them every once in a while. Naturally, there is a Sherlock Holmes connection.

Volume 1 contains Poul Anderson’s wonderful short story, “The Martian Crown Jewels,” which features a Martian detective named Syaloch, who lives on The Street of Those who Prepare Nourishment in Ovens and is consulted by human police officer named Inspector Gregg. It's a locked room mystery that takes place on a space ship. Good fun.

Anderson, who was one of the sweetest, shyest men I've ever met, was also a Sherlock Holmes and Solar Pons fan. He was inducted into the Baker Street Irregulars in 1960 as "The Dreadful Abernetty Business."

Which reminds me, I don't think I've mentioned that Boucher was invested in the BSI in 1949 as "The Valley of Fear."

I want to thank Jeffrey Marks for his help here and with other Starrett-related information. If you don't have a copy of his Boucher book, let me recommend it to you. It's worth the effort to hunt one down.

Until next time.