Riding 'The Wave': Vincent Starrett's little literary magazine

Although it lasted about as long as its namesake on the beach, The Wave had a big place in Starrett's literary career.

The late 1890s to the 1920s was a dramatic time in Chicago, as the city’s arts and culture scene exploded and came to rival New York. The Chicago Renascence (as Starrett spelled it) was a great time to be a writer and Vincent Starrett’s talents flourished during the period, even as he reveled in the flapper-era high spirits.

(NOTE: I’ll be quoting from two major sources: Starrett’s memoirs, Born in a Bookshop: Chapters from the Chicago Renascence, published in 1965 in Norman, Okla., by the University of Oklahoma Press; and “Vincent Starrett and The Wave: A Little Magazine of Chicago in the 1920s” by Charles L.P. Silet and Kay H. Silet , published in the Winter 1978 issue of The Great Lakes Review. Quotes from Starrett’s memoirs will be identified as Born; those from the Silets’ authoritative article will be sourced to Great Lakes.)

Prior to The Wave, Starrett had been a contributor to several other little literary magazines, most particularly The Double Dealer (1921-1926). The Double Dealer was based in New Orleans and looks like the Cajun answer to London’s infamous The Yellow Book, which had a brief but influential life from 1894 to 1897. Starrett’s occasional “Chicago Letter” in The Double Dealer leant an urban tint to the largely southern palette of contributors. His column was gossipy and bookish, as you would expect. Here’s an excerpt from the August-September 1921 number.

Oscar Williams, the poet, has come to live in Chicago, and is at present happily employed in Kroch’s International Bookstore. He is slight and slim. His hair has a permanent wave. He wears spectacles. He is very young. He writes excellent poetry. He argues ferociously. He does not like chop suey. His favorite contemporary is John Masefield. He passes his Sunday afternoons with the Bookfellows. (NOTE: As did Starrett.) He smokes cigarettes. He admires the stars. He has published in The Double Dealer.

Those familiar with Starrett's "Books Alive" newspaper column will recognize this as a precursor to that long-running Chicago feature.

A few years later, Starrett had his own turn at producing a little literary magazine. Here’s how it came about.

One evening a slim blond young man appeared on my door-step in Austin (a section of Chicago) and announced that he was Steen Hinrichsen and that he had come to see me about becoming the editor of a magazine he proposed to publish. He was himself an artist and a friend of artists and was in a position to obtain some of the best new art in Chicago, but he needed a literary editor who knew the local writers. … I gathered from Steen’s confidence and enthusiasm that he had found some financial backing for the magazine and that the matter of money simply did not arise. I was to be disillusioned on this score as time went on.” (Born, p. 204)

Starrett loved to portray himself as the dreamy poet for whom “the matter of money simply did not arise.”

Hinrichsen introduced Starrett—then 35 and eager for new experiences—into Chicago’s thriving Danish community. The preliminary work matched Starrett’s personality. “There were innumerable meetings and parties, both coeducational and stag, before the magazine was announced.” He hung out at Steen’s print shop where “now and then the décor of our conferences was improved by the presence and moral assistance of Steen’s lovely blonde sister, Inger.”

Starrett began asking his Chicago writer friends for contributions. He also went rummaging through the ephemera of his collection for rare and unpublished bits and pieces. It should be pointed out that while Starrett is known as a major Sherlockian collector, his interests and bibliophilic obsessions were far ranging. In other words, he had a lot of material to draw from.

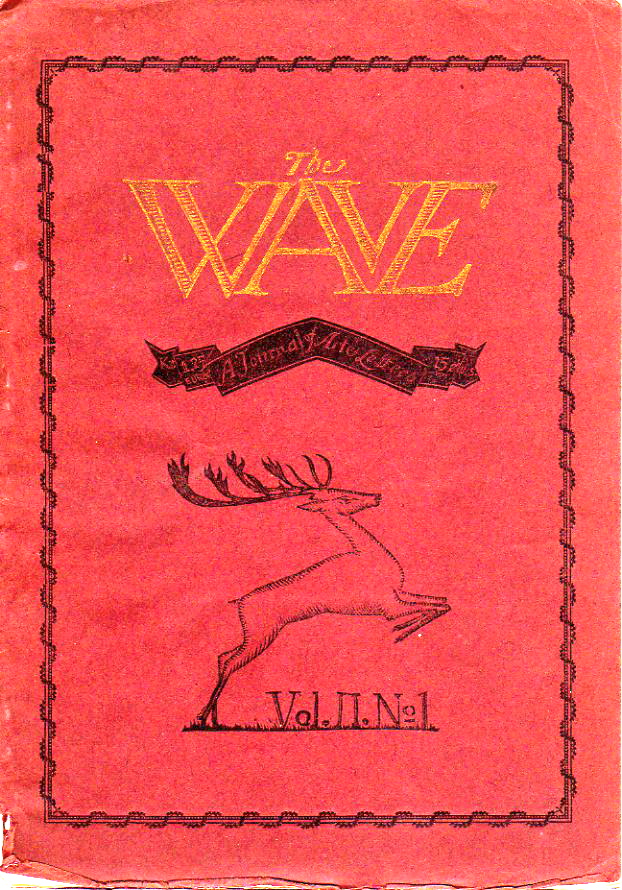

The result was The Wave, which the Silets characterize as “a quaint little magazine” that “represents probably one of the last responses to the famous Chicago literary renaissance.” (Great Lakes, p. 1)

The verse which gave rise to the name of Starrett and Hinrichsen's little magazine.

The name of the magazine came from a quatrain by William Saphier, first published in The Double Dealer:

I watched two little waves

marching to the shore.

One died with a yawn,

the second with a roar.

The bohemian nature of his new Danish friends had its influence on the magazine’s editorial policy. Starrett discussed the policy, such as it was, in the first issue's editorial column, which he called "Demi-Tasse:"

“The Wave is a magazine without a policy; at least, without any expressed editorial policy necessitating conformity with rules or opinions. … In short, we shall print what pleases us, hoping that it will please you.”

In his memoir, Starrett spends quite a few pages discussing the contributors and unusual items that were printed in The Wave. Looking back from the 1960s, it’s clear that 40 years later, he was still quite proud of the result. “I shall devote more space to The Wave than is importance merits, for editing it was a delightful human adventure.” (Born, p. 206)

Much of the delight came from Starrett's ability to print anything he wanted. For example, Starrett had an opportunity to publish the work of his hero, Arthur Machen, prose by friends like Ben Hecht and Carl Van Vechten, and poetry by several other friends. When there was space—which was often, since contributions were few—Starrett's own book collection offered up rare items regarding Oscar Wilde, Rudyard Kipling and Victor Hugo.

“It was a weird miscellany from first to last, I suppose, but an interesting one,” Starrett recalled. (Born, p. 207)

Starrett loved being editor of The Wave. Here is a rare copy of Gene Markey's illustration of Starrett holding a copy of the magazine, with a note by Starrett.

A sign of just how delighted Starrett was to be editor of The Wave can be seen in the caricature by Chicago illustrator and writer Gene Markey. (Markey produced two books of Chicago caricatures, and Starrett was in both.) This image is from Literary Lights: A Book of Caricatures, published in 1923 by Alfred A Knopf of New York.

Starrett is shown as a Victorian era dandy: top hat, waistcoat and gloves. A pocket watch with a tiny "VS" etched in it, is dangling from a ribbon. Starrett is also carrying a copy of The Wave. Entitled "An Eminent Victorian," Markey says under the image: "Vincent Starrett: 'What is the wild Wave saying?' "

In this rare autographed copy, Starrett has added the following:

"The wild Wave is saying, "This is a hell of a portrait!"

Markey's caricature is a sign that, for a short time as least, Starrett was intimately associated with his his little literary magazine, The Wave.

Starrett notes newspaper editors had fun with the name of The Wave when announcing the magazine's first publication. And there does seem to have been some genuine excitement from some editors, including The New York Times' Current Magazines column.

Heralding a new magazine is always a pleasure. Therefore let the open hand be extended to The Wave, published by Henrichsen & Lunoe, 2103 North Halsted Street, Chicago, and edited by Vincent Starrett. It bids fair to be an interesting periodical of a distinctly modern tinge.

The Contents page for the February 1922 number of The Wave.

No matter how delightful this welcome, the ugly realities of publishing a literary magazine soon came into play. Hinrichsen was a talented artist and printer, but no better businessman than Starrett, who recalls one particular example.

“Once he invited me to dine with him at a Danish restaurant of some repute and I saw him (Hinrichsen) in action. There were four of us in the party, Steen and Mrs. Hinrichsen and the blond Inger and myself. We dined royally with two kinds of wine and thereafter sat for an hour toasting one another with happy impartiality. Then Steen left us with a word of apology and engaged the proprietor, who was also the cashier, in a conversation that I could not follow because it was in Danish.”

After a commotion broke out between the two men, Starrett learned from Inger that Steen was trying to get the proprietor to accept an advertisement in The Wave as payment for dinner. The proprietor demurred. (Born, pp. 207-8)

There were other problems.

The typesetting was done, remarkably enough, by people for whom English was an incidental language, leading to many typos and irregularities. As the Stiles explain: “By the third number, Starrett was apologizing for the frequent typographical errors which were plaguing The Wave. He explained that the first issue was set by a Scandinavian compositor ‘without official connection; the second and third issues were set by a Russian compositor working for a Scandinavian newspaper.’ “ (Great Lakes, p. 7)

The headaches piled up. For example, the paper used for the magazine was fragile and began to fray even when fresh. (Indeed, although I own three issues, they are in such tenuous condition that I am reluctant to hold them forcibly open to be photographed.) The low number of subscribers coupled with the poor paper means there are very few copies around today. Individual issues can go for as much as $125, when they can be found.

Poor paper quality was nothing compared to the highly irregular nature of the publication. Deadlines, like an editorial policy, was loose at best. Even though The Wave was supposed to be a monthly, it had only five issues in 1922, just one in 1923 and the last two in 1924. Starrett recalled:

“Once Steen was unable to finance an issue of the magazine because again he was about to become a father. This was an occasion for one of our conferences, and I remember reproaching him hotly for being so careless at an important moment in The Wave’s history. But there was nothing either of us could do anything about it and in the end the baby won.” (Born, p. 209)

The final nail came when Hinrichsen and his family (Starrett doesn’t mention whether this included his sister) moved back to Denmark. Starrett had little to do with the last two issues, which were edited by his friend and fellow Chicago poet, Thomas Kennedy.

The Wave had only eight issues, but it did produce one additional collectible.

For Christmas 1922, the friends of Starrett, Hinrichsen and The Wave received a printed card produced by Hinrichsen Print of Chicago.

Inside was a lusty poem by Stephen Huguenot, alias Vincent Starrett. Huguenot was one of two "alter egos" created by Starrett for The Wave. The other was Edgar Savage. (Using these names, Starrett could print a poem by Huguenot, one by Savage, and then an editorial "Demi-Tasse" column under his own name, without looking like he was padding out his magazine.)

Back to the Christmas card. "Ballad" offered by Huguenot has an 18th century feel, with its old style spellings, tavern setting and salty subject matter. It is transcribed at the end of this article.

On the back of the card is a list of The Wave's entire staff. Starrett makes no mention of Triebel or Sahud in his memoirs. Perhaps, unilke Steen Hinrichsen, they did not have blond sisters.

About 100 of these cards were printed, according to Charles Honce's book, A Vincent Starrett Library.

The title page to next-to-last number of The Wave. Starrett says that while his name was listed as editor, he had little to do with the issue.

How did The Wave fit into the Chicago Renaissance, if at all? Here is how the Silets see it:

In retrospect, The Wave appears a curious anomaly. The magazine had a decidedly ‘90s’ look about it reminiscent of The Yellow Book. This tone was the result of Starrett’s interest in the period, which was reflected in his editorial decisions and Hinrichsen’s choice of art work, most of which had a quaint, old world flavor about it. In view of the fact that this journal came about, in part at least, as a response to the Chicago literary renaissance, a movement modernist in scope, the magazine seems slightly odd. It has a soft hat bohemianism about it.” (Great Lakes, p. 10)

Starrett’s view was that once Hinrichsen left for home, the magazine could not overcome the other problems.

Recalling the quatrain that gave the magazine its name, he said: “It died neither with a yawn nor a roar; it just petered out in spite of every effort to save its little life.”

Ballad

I care notte wheather snowe or sleete

Blow colde across ye weste;

There is a tavernne in our streete

Where I am wellcom gest.

What matter if it rainne or blowe,

How wette and dreare ye blast,

Whenne to that tavernne I maie goe

And staye til alle be past?

O there ye heart is brighte and warme,

And there ye stakes are raire,

And I am sayfe from anye storme

Besyde my crooked staire.

And comlie is ye barre-maide, sweete

Her lips, and smalle her shoe;

And, O! above her littel feete

Are stockings silke and and (sic) new.

Yette these be onlie halffe ye joies

Where soon I hope to bee—

Butte I shall go no further, boys,

Lest ye shall envye mee!

Stephen Huguenot