The tiny Starrett, Part 1

A long pair of blogs dedicated to a little subject: miniature books.

I like books. I like all kinds of books: hardbacks, paperbacks, oversized, leather bound, boxed or jacketed, illustrated or even, (let me take a breath here) e-books.

The Dog That Spoke French and a quarter.

But I have to say that one of the type of books that are made solely for the love of it, actually leave me a little cold. I’m speaking of miniature books.

Here's the problem:

You can’t comfortably read them, especially when you have fat thumbs and sketchy eyesight.

Simply handling them can be a challenge. (Quick story: I picked up several miniature books as part of an auction lot a decade ago and sold off the ones I didn’t want. A collector berated me for taking a photo of one book’s title page while holding it open with my thumb: “You have destroyed the value of the book by holding it open for the photo,” he wrote me. I sold it to another dealer.)

And trying to find a good way of storing, or showing them off is a real pain in the spine.

Title page of the miniature edition. Ignore my fat fingers.

Don’t get me wrong: While I am not a bookbinder, I do appreciate the skill and patience that goes into producing a miniature book. I have great respect for these mini works. The are a work of love, and rightfully deserve to be treated with care. As objects of art, they can be quite lovely.

But as books, their sheer size makes them impossible to read. And isn’t that the purpose of a book, regardless of its size?

At least three of Vincent Starrett’s essays have been published as miniatures, a fact that would have pleased the avid bookman. Let’s take a look.

(And if you’re a miniature book collector who wants to berate me for photographing these books while I hold them open, please send your emails to BooksAreMeantToBeRead@getalife.com.)

By the way, you'll notice I measure these books in inches. Yes, I know it's more accurate to do this in centimeters, but I failed metric system calculations, and use a good old American ruler. Deal with it.

The Dog that Spoke French

The Dog That Spoke French was published in Brandenton, Fla. by the Opuscula Press in 1992.

Coming in at a mere 2 and 5/8 inches square, this is the oldest story to get the miniaturization treatment, so far as I can tell. The article was originally published on Oct. 1, 1944 in Starrett's famous "Books Alive" column of the Chicago Sunday Tribune.

Here is how Starrett describes its origins:

For the origins of the story of Grosse Boule, the dog that spoke French, you must seek in the folklore of Old France, where it is variously — and somewhat more roguishly — told; but as I first heard this hilarious tale its setting was a French-Canadian parish in the province of Quebec.

The title literally translates to big ball.

Separated by about 48 years, these two editions of The Dog That Spoke French prove that a naughty joke never goes out of style.

The story is a literal shaggy dog's tale, a little racy, but nothing that could not be shared at a bar over a beer.

The miniature version was published in a limited edition of 200 in October, 1992. Robert F. Hanson is listed as the editor and publisher. It was published by the Opuscula Press in Bradenton, Florida.

The miniature version was not the first independent publication of this saucy tale.

The first publication was in a larger version by Edward J. Jacob of Peoria, Ill.. The date of its publication is not given in the document and there are no external indicators to tell you when it appeared. For what it's worth, Worldcat.com dates it as 1944, but I have seen at least one dealer give it a 1945 date. Let's call it 1944.

The booklet is a single page of fine linen, folded into 6 double leaves, with a red ribbon on the spine. It measures about 4 and 3/4 wide by 6 and 1/4 tall. My copy has a matching linen envelope. It is not clear how many of this version were printed, but it has the look and feel of a Christmas gift, so was probably a limited piece.

The big boy 1944 version is a lovely thing that is a pleasure to hold in your hand AND to read.

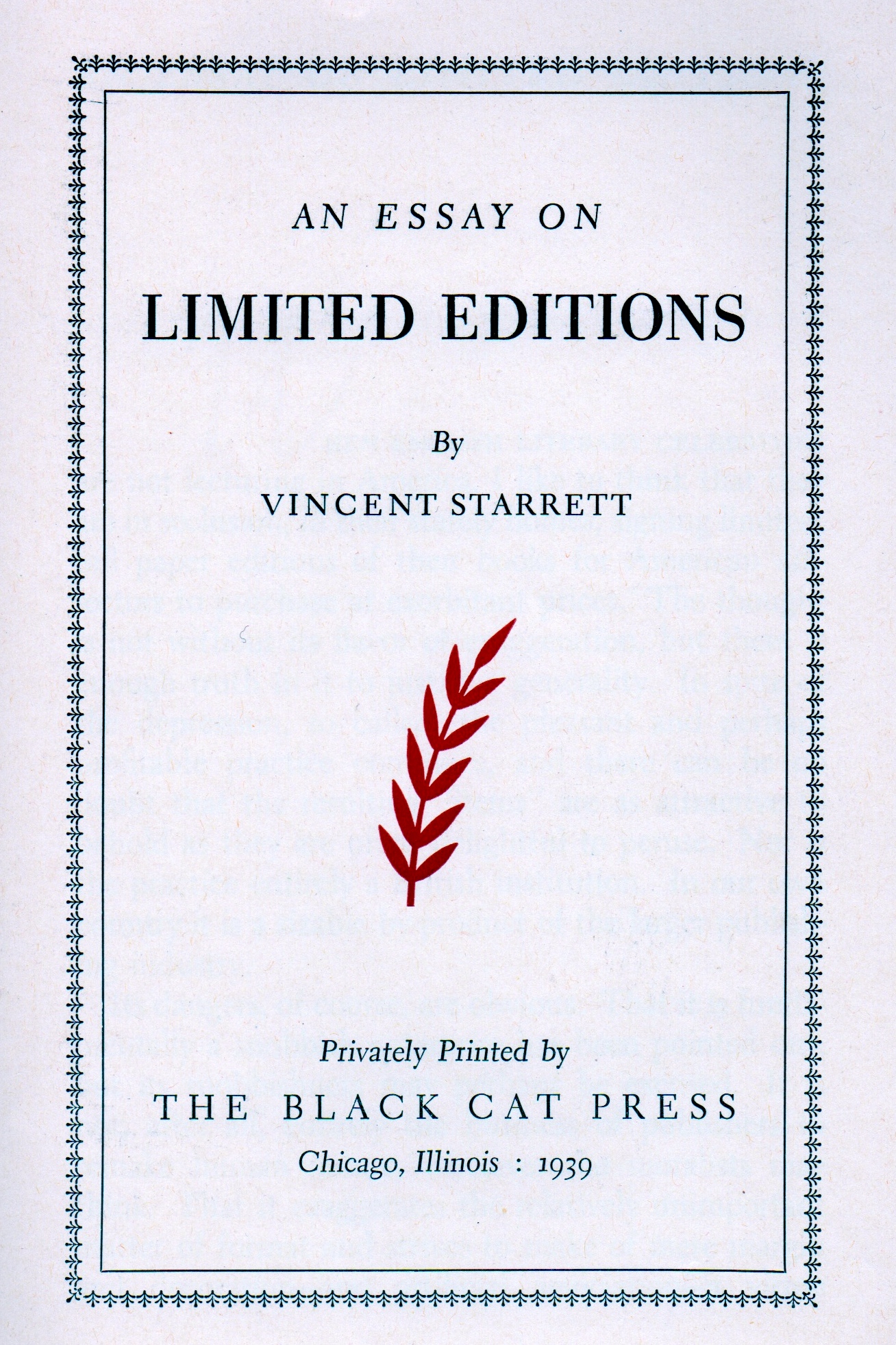

An Essay on Limited Editions

The title page for An Essay on Limited Editions from May, 1982.

Like The Dog That Spoke French, An Essay on Limited Editions is both a modern miniature volume and an older larger format booklet.

The handsomely gold stamped cover to the 1982 edition of An Essay on Limited Editions.

The tiny version of An Essay on Limited Editions was published in May 1982 by Black Cat Press in Skokie, Ill. It was published in a limited edition of just 249 copies. (We'll explain why in just a minute.) It's also the smallest of the three miniatures, measuring just 1 and 5/8 inches wide and 2 and 1/8 inches tall.

An Essay on Limited Editions is also a more attractive edition than The Dog That Spoke French, with gold stamping on the cover and spine, and attractive end papers.

The origin of this essay appears to be in a larger format version published in April 1939 ALSO by The Black Cat Press of Chicago. The older, larger version is 9 inches high by 6 inches wide. Coming in at 10 pages, it was published in a limited edition of 250 copies, one more than the baby edition of 1982.

The colophon states the essay was printed by hand on Alexandria plate finish paper and was set in the Electra fonts of W.A. Dwiggins. The pages have a silky feel and are lovely to handle.

It's no surprise that a book lover like Starrett would limited editions by writing about them. He must have been highly honored to have this essay published as a keepsake, especially as the high quality paper and typesetting makes the little pamphlet the kind of keepsake that's a pleasure to handle, all these many years later.

As Starrett himself observed in the essay:

"And when an author finds himself thus honored by the curious distinction of limitation, I think he should be properly impressed. It is somewhat of an accolade. If nothing else (and if he cares about survival), he will outlast his brothers in the sheerly physical matter of durability and dress. It is no secret, and no legend, that the average trade volume is printed upon an inferior quality of paper, and that it will disintegrate with the passage of time. One thinks of many such whose ultimate existence as dust it is possible to view with composure and a certain pleasure; but one also thinks of the finer flowerings and wishes them, with complete altruism, a longevity commensurate with their excellence."

Now, why would the 1939 edition have 250 copies and the 1982 only 249? It's probably because of something Starrett says in the essay.

Starrett speculates a little on what a collector would consider to be the perfect number that would make the "perfect limited edition."

"It was Eugene Field — was it not? — who once lusted for the perfect limited edition. Let there be three copies only, he said in effect, one for me, one for the publisher, and a third to be burned. Well, well, I should not, myself, have bothered about the publisher."

After a bit more drollery, Starrett quotes another bookman, Laurence Woodworth, as saying "that an edition of more than two hundred and fifty copies was not a limited edition."

Here you have the little joke the folks at the Black Cat Press were playing. By printing only 249 copies of their miniature, they kept themselves with the stricture that Woodworth, and Starrett, seemed to feel was necessary for any limited edition.

By the way, my copy of the 1939 printing came with a nice little association item: a postcard stamped Oct. 29, 1947, sent by Starrett to a Madeline Chirille (sp?) Johnson. Mrs. Johnson had apparently recently moved to San Francisco. The card is reprinted here.

A postcard to Madeline Johnson from Vincent Starrett. It's unclear what book he is referring to here, but the card is notable because it contains a rare mention of Starrett's second wife, Ray.

Also, note the way in which Starrett draws a little circle around the period of each sentence. That is a device any old newspaper reporter from the period would have recognized as a standard copy mark.

Okay, I'm a little tired now. There is a third miniature book to profile, but this is getting long, so wait for the next exciting edition of: The Tiny Starrett.