The writer, the pig and the baseball team

I keep the books in my Starrett library shelved in a general order: Early works on Machen, Stevenson, Crane and Bierce over here; poetry over there; Sherlock on that shelf; books about books in the center and mysteries on the shelves down below.

And then there’s this book.

The dust jacket to Starrett's only juvenile story, published in 1957.

The Great All-Star Animal League Ball Game

It’s sui generis, and doesn’t fit with anything other Starrett work. Written by Starrett with illustrations by the talented Kurt Wiese, it’s the tale of a baseball game played entirely by a team of forest and barnyard animals.

In fact, it’s so unlike any of his other work that it’s hard to believe Starrett wrote it, except for the fact that he was a lifelong baseball fan. Remember that Starrett named his most famous detective Jimmie Lavender, after a Chicago ballplayer named Jimmy Lavender.

Back to The Great All-Star Animal League Ball Game.

The book was published in 1957 by Dodd, Mead & Company. By this point, Starrett had given up fiction and poetry and was focusing his efforts largely on his “Books Alive” column for the Chicago Tribune.

The genesis of the book is a little vague. Starrett only briefly references The Great All-Star Animal League Ball Game in his memoir, Born in a Bookshop, page 306.

After naming a number of books he wrote, Starrett comes to The Great All-Star Animal League Ball Game.

“This last title, my first and only juvenile, had been lurking in my subconscious for years, perhaps since boyhood. I am glad I got around to it at last, for it continues to bring me delightful letters from small boys, and sometimes, girls in all parts of what H.L. Mencken used to call the ‘federal union.’ “

The title page.

The plot is pretty simple. The All-Star Animal League baseball game is to be played by a group of animals from Thatcher’s Woods. The game had been delayed by three years because the only ball the animals owned had been hit into the woods by Homer Wolff, “So the game had to be called off.”

But now the ball had been found by Squirrel Nutley in the V of a tall oak, and it was time once again to “play ball!”

The stakes had been raised beyond the bragging rights that go to the winning team.

“A man out in Hollywood, hearing of the unusual event, had offered the winning team a place in a color cartoon he was making, and everyone was fixing to be a screen star.”

On game day, Rennie Foxx of the Deep Woods Pirates was set to go up against Shep Collie of the Barnyard Braves. There is a great deal of trickery and shenanigans from both teams. For example, Rennie Foxx put Tim Turtle up to bat late in the game. Tim was so tiny that he had practically no strike zone and earned a base on balls. Tim was so slow ambling down to first base that the Pirates all went to get a bite to eat.

An opening spread.

The Barnyard Braves won the game and “Everybody and his brother who had been rooting for the Barnyard Braves yelled ‘Hurrah!’ or ‘Oh, my Aunt Susie!’ or ‘What did I tell you?’” Naturally the last hit (or rather kick ) by a donkey named Dusty Roads brought in to pitch hit travels so far it is lost once again and a rematch is in doubt.

The winning hit, er, kick.

As you can see, the book is profusely illustrated, and it is here that Starret was fortunate indeed. Kurt Wiese (April 22, 1887 - May 27, 1974) was a contemporary of Starrett’s but told stories through illustrations rather than words.

A native of Germany, Wiese traveled the world before settling with his wife on a large farm in Kingwood Township, N.J. His work drew recognition from the Caldecott and Newberry committees. Over the course of his career, Wiese illustrated more than 300 children’s books, with the best-known single volume being the pre-Disney Bambi.

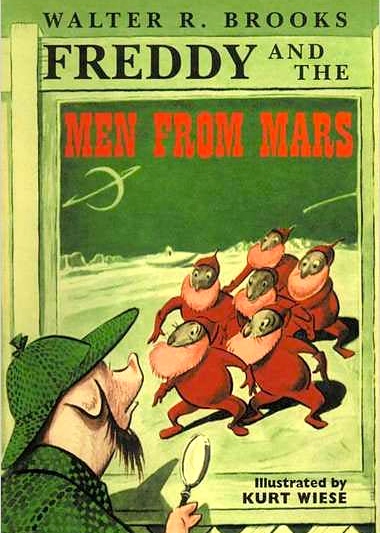

Wiese was no stranger to groups of animals acting like humans. Starting in 1927, Wiese partnered with writer Walter R. Brooks for a series of books that feature a barnyard full of animals.

Although he did not take center stage until a few sequels later, Freddy the Pig became the hero of the animals’ adventures.

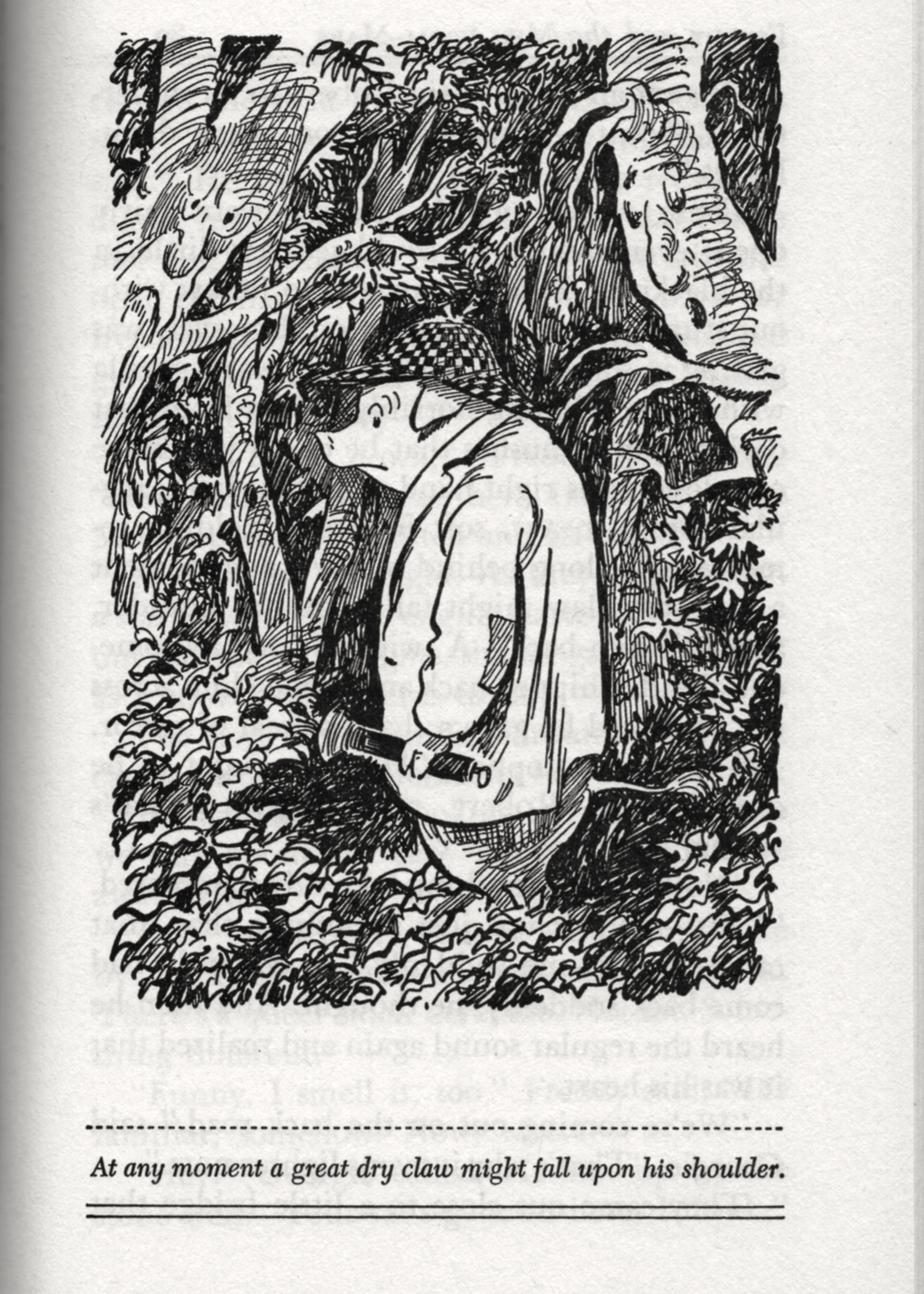

Freddy took on several personas in the series, including a detective. Inspired by a copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Freddy put on a deerstalker and acted like a childish version of the original.

As you can see in in the accompanying illustration, Freddy acted as a detective in more than one volume, including Freddy the Detective and Freddy and the Men from Mars.

The dedication page

By the way, The Great All-Star Animal League Ball Game was dedicated to Clark Kinnaird as “A small token of a large friendship and gratitude.” Kinnaird was a long-time writer and editor for the King Features Syndicate, which sold news features, columns and comics to newspapers around the world.

The two men likely knew one another as fellow writers, but there is a stronger connection. Starrett aficionado Peter Ruber, in his introduction of The Memoirs of Jimmie Lavender explains why Starrett was so grateful to Kinnaird. It turns out that Kinnaird was a fan of the Jimmie Lavender mysteries and “in the late 1940s, Clark Kinnaird at King Features Syndicate called on Starrett to rewrite a number of the Lavender (stories) so that they would fit as six-part serials in daily newspapers. … Over the next 15 years King Features serialized more than two dozen of the old Lavender mysteries (as well as many of Starrett’s other stories.)”

Starrett was clearly grateful for Kinnaird’s efforts at turning old Jimmie Lavender stories into new moneymakers.

So that’s the story of the writer, the pig and the baseball team.

Now if I can only figure out the right shelf for this book.

The more you know:

There is a nice biographical essay on illustrator Kurt Wiese at “Through the Magic Door”.

The “Friends of Freddy” website has a good essay on Walter R. Brooks. The site also has a complete list of the Freddy books.